論文ID: CJ-23-0543

論文ID: CJ-23-0543

Background: Limited studies have demonstrated sex differences in the clinical outcomes and quality of care among elderly patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Methods and Results: Using nationwide cardiovascular registry data collected in Japan between 2012 and 2019, we enrolled patients aged ≥45 years. The 30-day and all in-hospital mortality rates, as well as process-of-care measures, were assessed, and mixed-effects logistic regression analysis was performed. A total 254,608 patients were included and stratified into 3 age groups: middle-aged, old and oldest old. The 30-day mortality rates for females and males were as follows: 3.0% vs. 2.7%, with an adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 1.17 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.01–1.36, P=0.030) in middle-aged patients; 7.2% vs. 5.8%, with an OR of 1.14 (95% CI: 1.09–1.21, P<0.001) in old patients; and 19.6% vs. 15.5% with an OR of 1.17 (95% CI: 1.09–1.26, P<0.001) in the oldest old patients. Moreover, significantly higher numbers of female AMI patients across all age groups died in hospital, as well as having fewer invasive procedures and cardiovascular prescriptions, compared with their male counterparts.

Conclusions: This nationwide cohort study revealed that female middle-aged and elderly patients experienced suboptimal quality of care and poorer in-hospital outcomes following AMI, compared with their male counterparts, highlighting the need for more effective management in consideration of sex-specific factors.

Advancements in healthcare services, emergency systems, and reperfusion therapy have improved clinical outcomes of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) globally, despite its persistent status as a major cause of death, imposing substantial socioeconomic pressure.1–3 The clinical outcomes following AMI considerably vary according to baseline clinical risk profiles composed of biologic, demographic, and geographic characteristics. Under these circumstances, quality of care has been getting attention in the pursuit of improving the clinical outcomes for AMI patients.4,5

Sex is a contributory factor for in-hospital prognosis and quality of care among AMI patients. Researchers have reported that young female patients experience inferior quality of care and poorer in-hospital outcomes following AMI, compared with their male counterparts, and the sex differences are attenuated by aging.6–10 In addition, biological characteristics, such as female hormones, gestation and its related issues, history of early menopause, and others including psychological, social, economic, and cultural factors, can contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease risk in females.11

Although disparities in outcomes and quality of care based on sex have been predominantly reported in young AMI patients, various sex-specific factors affect clinical outcomes irrespective of age. Given the aging population scenario faced by many countries, including Japan, effective management strategies for elderly patients with critical illnesses are required to enhance both life expectancy and healthy life years, while considering regional and demographic variations. In this study, we aimed to determine the association between sex and in-hospital death, as well as quality of care, among elderly patients admitted for AMI in Japan, using nationwide cardiovascular registry data.

Data were aggregated from a Japanese registry of all cardiac and vascular diseases-diagnostics procedure combination, the JROAD-DPC database, obtained from hospitals participating in the JROAD study in Japan.4,12 The JROAD data, including hospital attributes, were combined with DPC data, which are medical claims data associated with acute-care hospitalization. This encompassed patient demographics, clinical data inclusive of pharmacological interventions and procedural details. Of all data collected between 2012 and 2019, a total of 313,421 adult AMI patients across 1,068 hospitals, aged ≥45 years, with a primary diagnosis of AMI, were enrolled. After excluding patients with an unevaluable Killip classification on admission and those with missing values of which variable has missing rates less than 1%, the study population comprised 254,608 patients across 953 hospitals.

The primary outcome was 30-day in-hospital death, and secondary outcomes were all in-hospital deaths, and process-of-care measures including medications and procedures to treat AMI. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine (approval no. ERB-C-2194), and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical AnalysisAll statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.2.0.13 Baseline characteristics were summarized and compared dichotomously between males and females within each age-defined groups. Categorical values were subjected to the Chi-squared test. Continuous values were subjected to a t-test if normally distributed, and the Mann-Whitney U test if non-normally distributed. To assess in-hospital deaths and process-of-care measures, mixed-effect logistic regression analysis was performed. Multivariables incorporated both patient characteristics (age, sex, obesity as defined by body mass index (BMI) ≥30, Charlson score, Killip class on admission, and Brinkman index) and hospital attributes (annual volume of AMI patients, annual number of emergency percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) procedures, number of cardiologists, number of cardiology beds, and hospital training status). The hospital identifier was integrated as a random-effect variable toward the intercept. A two-sided P value <0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

The compiled data of the 254,608 patients hospitalized due to AMI were divided into 3 age groups: middle age ≥45 to 65 years (n=78,403), old ≥65 to 85 years (n=144,166) and oldest old ≥85 years (n=32,039) (Figure 1). The baseline demographics of these patients are shown in Table 1. The prevalence of obesity (defined as BMI ≥30) was higher in females than males in all age groups. A distinct trend was observed in the Killip classification with increasing age: a decrease in the proportion of Killip class 1, accompanied by a corresponding increase in the proportions of Killip classes 2, 3, and 4. In the elderly groups, the percentage of patients classified as Killip 1 was least, whereas the proportion of those classified as Killip 3 or 4 was elevated in females. The Charlson comorbidity score exhibited a higher value in females relative to males in the middle-aged group, but, conversely, a lower score was observed in the elderly group. Females incurred lower cost during hospitalization for AMI than males across all age groups. Compared with females, males in the elderly groups were more likely to be admitted to hospitals with a greater number of cardiologists, increased annual volume of AMI hospitalizations, and a high number of emergency PCI cases.

Flowchart of the data filtering and stratification process. Patients with unevaluable Killip classification and missing values for variables with a missing rate <1% were excluded. Ultimately, 254,608 patients across 953 hospitals were enrolled for analysis. The data were stratified into distinct age groups. AMI, acute myocardial infarction.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized With AMI

| Characteristics | Age ≥45 to 65 years | Age ≥65 to 85 years | Age ≥85 years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (88.2%, n=69,227) |

Female (11.7%, n=9,176) |

P value | Male (72.4%, n=104,387) |

Female (27.5%, n=39,779) |

P value | Male (45.5%, n=14,581) |

Female (54.4%, n=17,458) |

P value | |

| Patient characteristics | |||||||||

| Age (years) | 56.2 (5.6) |

57.3 (5.6) |

<0.001 | 73.5 (5.5) |

75.6 (5.5) |

<0.001 | 88.1 (2.9) |

89.2 (3.5) |

<0.001 |

| BMI ≥30 (%) | 7,565 (10.9) |

1,091 (11.8) |

<0.001 | 2,766 (2.6) |

1,745 (4.3) |

<0.001 | 151 (1.0) |

303 (1.7) |

<0.001 |

| Brinkman index | 1,573 (3,348) |

1,081 (3,453) |

<0.001 | 1,702 (3,473) |

910 (2,888) |

<0.001 | 1,765 (3,575) |

843 (2,739) |

<0.001 |

| Killip 1 (%) | 40,333 (58.2) |

5,334 (58.1) |

0.90 | 52,763 (50.5) |

19,380 (48.7) |

<0.001 | 5,894 (40.4) |

6,408 (36.7) |

<0.001 |

| Killip 2–4 (%) | 28,894 (41.8) |

3,842 (41.9) |

0.88 | 51,624 (49.5) |

20,399 (51.3) |

<0.001 | 8,687 (59.6) |

11,050 (63.3) |

<0.001 |

| Killip 2 (%) | 17,614 (25.4) |

2,352 (25.6) |

0.77 | 28,953 (27.7) |

11,305 (28.4) |

0.053 | 4,417 (30.2) |

5,431 (31.1) |

0.25 |

| Killip 3 (%) | 4,282 (6.1) |

564 (6.1) |

0.90 | 8,849 (8.4) |

3,783 (9.5) |

<0.001 | 1,789 (12.2) |

2,339 (13.3) |

0.0087 |

| Killip 4 (%) | 6,998 (10.1) |

926 (10.0) |

0.97 | 13,822 (13.2) |

5,311 (13.3) |

0.63 | 2,481 (17.0) |

3,280 (18.7) |

<0.001 |

| Charlson score | 1.97 (0.99) |

2.06 (1.12) |

<0.001 | 2.24 (1.21) |

2.18 (1.16) |

<0.001 | 2.36 (1.28) |

2.21 (1.13) |

<0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 47,878 (69.1) |

6,134 (66.8) |

0.053 | 68,000 (65.1) |

25,791 (64.8) |

0.61 | 8,316 (57.0) |

10,043 (57.5) |

0.64 |

| Diabetes (%) | 22,155 (32.0) |

2,919 (31.8) |

0.79 | 34,111 (32.6) |

12,126 (30.4) |

<0.001 | 3,257 (22.3) |

3,578 (20.4) |

0.0013 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 50,892 (73.5) |

6,231 (67.9) |

<0.001 | 64,621 (61.9) |

24,327 (61.1) |

0.20 | 6,613 (45.3) |

7,590 (43.4) |

0.037 |

| Dialysis (%) | 1,524 (2.2) |

393 (4.2) |

<0.001 | 3,696 (3.5) |

1,426 (3.5) |

0.70 | 406 (2.7) |

312 (1.7) |

<0.001 |

| Duration of hospitalization (days) |

14.6 (10.8) |

14.8 (11.7) |

0.056 | 16.7 (14.3) |

17.8 (15.5) |

<0.001 | 18.6 (16.9) |

19.0 (17.3) |

0.059 |

| Hospitalization cost (USD) |

20,301 (14,184) |

18,838 (13,776) |

<0.001 | 21,714 (14,462) |

21,396 (15,144) |

<0.001 | 19,778 (13,594) |

18,184 (13,057) |

<0.001 |

| Hospital characteristics | |||||||||

| Training facility (%) | 68,937 (99.5) |

9,131 (99.5) |

0.96 | 103,910 (99.5) |

39,598 (99.5) |

1.0 | 14,502 (99.4) |

17,335 (99.2) |

0.92 |

| Cardiologists | 7.37 (6.79) |

7.27 (6.60) |

0.20 | 7.47 (6.92) |

7.39 (7.02) |

0.074 | 7.07 (6.74) |

6.69 (6.07) |

<0.001 |

| Cardiovascular beds | 45.3 (23.9) |

45.2 (24.1) |

0.81 | 45.7 (24.6) |

45.5 (24.8) |

0.25 | 44.6 (23.9) |

44.4 (24.2) |

0.54 |

| Hospitalizations for AMI per year |

105 (63.5) |

105 (64.7) |

0.60 | 106 (65.3) |

105 (65.6) |

0.021 | 102 (64.5) |

99.6 (64.9) |

<0.001 |

| Emergency PCI per year |

82.0 (52.9) |

81.4 (54.2) |

0.30 | 82.5 (54.5) |

81.8 (54.9) |

0.031 | 77.4 (53.5) |

77.4 (54.0) |

0.0034 |

Patients were stratified by age, and compared between male and female. Data presented as mean (SD) for numerical values, and % for categorical values. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; BMI, body mass index; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SD, standard deviation.

Association Between Sex and Quality of Care of Patients Hospitalized With AMI

A variety of process-of-care measures were examined to evaluate the association between sex and the quality of care for patients hospitalized with AMI (Table 2). The procedure rate of PCI was significantly lower in females compared with males across all age groups: the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) was 0.37 (95% CI: 0.35–0.40, P<0.001) in middle-aged patients; 0.71 (95% CI: 0.68–0.74, P<0.001) in old patients; and 0.74 (95% CI: 0.70–0.79, P<0.001) in the oldest old patients. Mechanical circulatory support devices such as intra-aortic balloon pumping (IABP) and veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) were significantly less often used in females than in males across all age groups. The procedure rate of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) was significantly lower in females compared with males only in the oldest old patients. Thus, female AMI patients were less likely to undergo invasive procedures than their male counterparts.

Process-of-Care Measures in Patients Hospitalized With AMI

| Process-of-care measures |

Age ≥45 to 65 years | Age ≥65 to 85 years | Age ≥85 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female vs. male OR (95% CI), P value |

Female vs. male OR (95% CI), P value |

Female vs. male OR (95% CI), P value |

|

| PCI | 83.5% vs. 92.8% 0.37 (0.35–0.40), <0.001 |

86.1% vs. 90.1% 0.71 (0.68–0.74), <0.001 |

72.6% vs. 79.5% 0.74 (0.70–0.79), <0.001 |

| IABP | 11.2% vs. 13.9% 0.72 (0.66–0.78), <0.001 |

14.8% vs. 16.3% 0.85 (0.82–0.88), <0.001 |

11.0% vs. 13.5% 0.78 (0.72–0.84), <0.001 |

| VA-ECMO | 1.9% vs. 2.4% 0.83 (0.70–0.99), 0.045 |

1.9% vs. 2.4% 0.84 (0.77–0.91), <0.001 |

0.76% vs. 1.3% 0.61 (0.47–0.79), <0.001 |

| CABG | 1.8% vs. 1.9% 0.88 (0.74–1.04), 0.15 |

2.5% vs. 2.7% 0.94 (0.87–1.02), 0.18 |

0.49% vs. 1.2% 0.42 (0.32–0.55), <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 71.2% vs. 78.1% 0.67 (0.63–0.70), <0.001 |

71.1% vs. 73.2% 0.91 (0.89–0.94), <0.001 |

58.0% vs. 61.5% 0.93 (0.89–0.98), <0.001 |

| β-blocker | 62.6% vs. 71.2% 0.63 (0.60–0.67), <0.001 |

65.2% vs. 67.2% 0.94 (0.92–0.97), <0.001 |

52.7% vs. 56.1% 0.94 (0.89–0.98), 0.017 |

| Statin | 84.6% vs. 90.4% 0.57 (0.53–0.61), <0.001 |

81.9% vs. 83.4% 0.97 (0.94–1.00), 0.12 |

64.4% vs. 68.8% 0.91 (0.87–0.96), 0.0016 |

| Aspirin | 94.1% vs. 97.0% 0.47 (0.42–0.52), <0.001 |

93.3% vs. 95.0% 0.78 (0.74–0.82), <0.001 |

85.5% vs. 89.2% 0.79 (0.73–0.85), <0.001 |

First line in each row represents the procedure and prescription rates. Adjusted ORs were calculated for female to male AMI patients in each age group. ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme-inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CI, confidence interval; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pumping; OR, odds ratio; VA-ECMO, veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

The prescription of standard medications was also examined as a process-of-care measure for hospitalized AMI patients. Specifically, the prescription of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) was significantly lower in female patients than males across all age groups: AOR 0.67 (95% CI: 063–0.70, P<0.001) in middle-aged patients; 0.91 (95% CI: 0.89–0.94, P<0.001) in old patients; and 0.93 (95% CI: 0.89–0.98, P<0.001) in the oldest old patients. Further, the prescriptions for β-blockers exhibited a similar trend of being significantly lower in females compared to males: an adjusted OR was 0.63 (95% CI: 0.60–0.67, P<0.001) in middle-aged patients; an OR was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.92–0.97, P<0.001) in old patients; and an OR was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.89–0.98, P<0.001) in oldest old patients. Furthermore, the prescription of aspirin was also significantly lower in females compared to males: an adjusted OR was 0.47 (95% CI: 0.45–0.52, P<0.001) in middle age patients; an OR was 0.78 (95% CI: 0.74–0.82, P<0.001) in old patients; and an OR was 0.79 (95% CI: 0.73–0.85, P<0.001) in oldest old patients. Prescription of statins for females was significantly less in the middle-aged and oldest old groups. Taken together, these findings indicate that female AMI patients were less likely to receive guideline-indicated medications in hospital compared with their male counterparts.

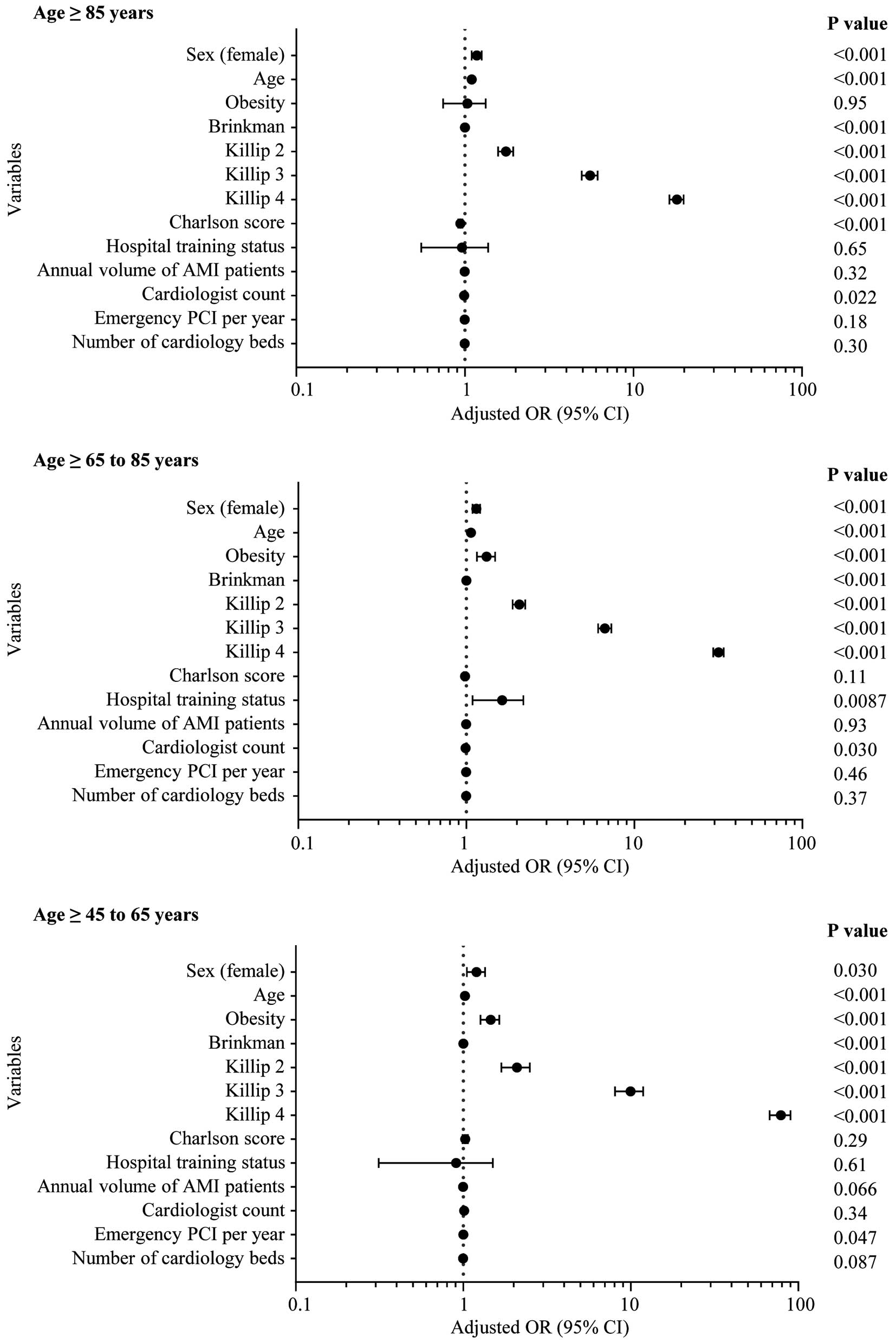

Association Between Sex and In-Hospital Death of Patients Hospitalized With AMIThe 30-day and all in-hospital mortality rates were investigated to evaluate the association between sex and in-hospital outcomes (Table 3). The 30-day mortality rates for females and males were as follows: 3.0% vs. 2.7% (AOR 1.17, 95% CI: 1.01–1.36, P=0.030) in middle-aged patients; 7.2% vs. 5.8% (AOR 1.14, 95% CI: 1.09–1.21, P<0.001) in old patients; and 19.6% vs. 15.5% (AOR 1.17, 95% CI: 1.09–1.26, P<0.001) in the oldest old patients. All in-hospital mortality rates of females and males were as follows: 3.4% vs. 3.0% (AOR 1.19, 95% CI: 1.03–1.37, P=0.014) in middle-aged patients; 8.0% vs. 6.7% (AOR 1.10 (95% CI: 1.04–1.16, P<0.001) in old patients; and 21.4% vs. 17.3% (AOR 1.15 (95% CI: 1.08–1.23, P<0.001) in the oldest old patients. The effects of all variables for the 30-day in-hospital mortality rate are depicted in Figure 2. Collectively, the 30-day and all in-hospital mortality rates for patients hospitalized with AMI were significantly higher for females than for males across all age groups.

In-Hospital Mortality Rates of Patients Hospitalized With AMI

| In-hospital mortality rate |

Age ≥45 to 65 years | Age ≥65 to 85 years | Age ≥85 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female vs. male OR (95% CI), P value |

Female vs. male OR (95% CI), P value |

Female vs. male OR (95% CI), P value |

|

| 30-day | 3.0% vs. 2.7% 1.17 (1.01–1.36), 0.030 |

7.2% vs. 5.8% 1.14 (1.09–1.21), <0.001 |

19.6% vs. 15.5% 1.17 (1.09–1.26), <0.001 |

| All | 3.4% vs. 3.0% 1.19 (1.03–1.37), 0.014 |

8.0% vs. 6.7% 1.10 (1.04–1.16), <0.001 |

21.4% vs. 17.3% 1.15 (1.08–1.23), <0.001 |

First line in each row represents the mortality rate. Adjusted ORs of 30-day and all in-hospital mortality were calculated for female to male patients hospitalized with AMI in each age group. Abbreviations as in Tables 1,2.

Effect of variables on in-hospital mortality rates. Adjusted odds ratio (OR) for 30-day in-hospital death was plotted with a logarithmic scale on the x-axis. Error bar indicates 95% confidence interval (CI). AMI, acute myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Next, we included process-of-care measures as variables for the model. Sex (female) continued to be a significant risk factor for 30-day in-hospital death among elderly AMI patients except for middle-aged patients, even when considering the adjustment by process-of-care measures (Supplementary Figure).

The main finding of this study is the existence of sex differences in both the care and in-hospital prognosis of patients hospitalized with AMI within Japan, a nation at the forefront of longevity. Despite adjusting crucial factors such as age and Killip classifications, relative to their male counterparts elderly Japanese female patients hospitalized for AMI were less likely to receive invasive procedures such as PCI or CABG, or guideline-indicated standard care, and subsequently experienced higher in-hospital mortality rates.

Our data elucidated a sex difference in in-hospital mortality rates among the middle-aged and elderly groups. Several studies have proposed prehospital mechanistic causes of sex differences in death after AMI. It is postulated that young females may develop coronary artery disease through divergent biological, psychological, sociological, economic, and cultural factors compared with males.11 Higher prevalence of typical coronary risk factors could also exacerbate adverse clinical outcomes in young females relative to their male counterparts.14,15 Despite sex-specific causal factors affecting clinical outcomes regardless of age, many previous investigations, largely conducted in other Western countries, suggest that only young adult females exhibit higher short- and long-term mortality rates compared with age-matched males after AMI. On the other hand, some regional studies in Japan have not observed a sex difference in deaths due to AMI.16,17 A study using the JROAD-DPC data suggested an influence of regionality represented by population density on in-hospital deaths among AMI patients in Japan.18 Overall, this evidence suggest that the effect of sex on outcomes following AMI can differ among regions.

Quality of care plays a pivotal role in the discrepancies in clinical outcomes of AMI for males and females. Indeed, adherence to evidence-based, guideline-indicated treatment can ameliorate the mortality rates among AMI patients.19 Besides patient characteristics and hospital attributes, the physician is also an important factor in the sex differences in quality of care for AMI patients because the physician’s ability or discretion can bias a patient’s management and clinical outcome. Physicians tend to underestimate the cardiovascular risks among females, with subsequent suboptimal risk prevention efforts.20–22 Our results are consistent with previous studies that identified a propensity for female AMI patients to receive less guideline-indicated care and consequently experience higher mortality rates than their male counterparts.23 Reports have also indicated that females suffering from AMI confront a delay in the initiation of therapeutic interventions compared with males, again attributable to underestimation of cardiovascular risks and different manifestation of symptoms.24,25 In this study, the hospitals to which the elderly females were admitted had fewer cardiologists and less experience in treating AMI. A report by Alabas et al showed that sex differences in deaths after AMI were considerably mitigated by administration of guideline-indicated treatments.26 Taken together, the effect of the quality of care on clinical outcomes after AMI could substantially alter age-specific sex-related mortality rates.

Study LimitationsThere are several limitations that derive from the nature of the JROAD-DPC dataset. First, it did not include laboratory data. Second, it lacked ECG information, and ST deviation was not determinable. Third, it also lacked information about frailty and cognitive function as well as socioeconomic status. Finally, the cause of death was undisclosed.

In conclusion, this nationwide large cohort study revealed that middle-aged and elderly female patients received suboptimal quality of care during hospitalization due to AMI and subsequent poorer in-hospital outcomes compared with their male counterparts. Delivering the necessary medical care will improve patient outcomes, and more attention to providing guideline-indicated treatment, while considering sex-specific factors, for female patients admitted with AMI will reduce in-hospital mortality rates.

This study was supported by Japanese Circulation Society Grant for Future-Pioneering Doctors for Clinical Research, and Foundation for Total Health Promotion.

None.

The Ethics Committee of Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine (approval no. ERB-C-2194).

The deidentified participant data will not be shared.

Please find supplementary file(s);

https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-23-0543