論文ID: CJ-24-0666

論文ID: CJ-24-0666

Background: Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) is an under-recognized cause of heart failure (HF) in older adults. Delayed ATTR-CM diagnosis may result in more advanced symptoms. This study describes the journey of Japanese patients with ATTR-CM.

Methods and Results: This retrospective non-interventional study used the DeSC Healthcare database. Patients aged ≥18 years at the index date (date when ATTR-CM was first diagnosed or date of first tafamidis 80 mg prescription, whichever was earlier) and who had received ≥1 tafamidis 80 mg prescription or ≥1 specific ATTR-CM diagnosis, excepting “suspected diagnosis”, at any time between April 1, 2014 and August 31, 2021 were included. The median age of patients was 79.0 years, and 79.9% (n=239) were male. The most frequently observed comorbidities defined as indicating the onset of ATTR-CM were HF (87.9%), atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter (50.2%), and conduction disorders (17.2%), with a median time from onset to index date of 15.5, 14.0, and 9.0 months for each comorbidity, respectively. Lumbar spinal stenosis (23.9%), neuropathy (13.0%), and carpal tunnel syndrome (7.5%) were common extracardiac symptoms, with a median time from the appearance of these symptoms to index date of 19.0, 5.0, and 18.0 months, respectively.

Conclusions: There was a delay between the appearance of cardiac and extracardiac comorbidities of ATTR-CM and its diagnosis in real-world Japanese clinical settings, emphasizing the need for early diagnosis of ATTR-CM.

Cardiac amyloidosis can result from the deposition of transthyretin (ATTR) or misfolding of monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains (light-chain amyloidosis [AL]).1 Depending on the sequence of the transthyretin (TTR) gene, ATTR is further categorized as wild-type (ATTRwt; no mutation) or variant (ATTRv; a mutation is present) ATTR.1,2 Deposition of misfolded ATTR in the myocardium results in cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM).3 Fluid retention, palpitations, atrial fibrillation (AF), and thromboembolism are some of the commonly presenting signs and symptoms of ATTR-CM.4 In addition, cardiologists should consider screening patients with a history of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and/or lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) for ATTR-CM.1,4–7 It is important to distinguish between the 3 typical types of amyloidosis (i.e., ATTRwt, ATTRv, and AL) from other types of cardiomyopathy, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and hypertensive heart disease (HHD), to introduce disease-specific treatments at an early stage to optimize patient outcomes and prevent further disease complications.1

Patients with ATTR-CM often undergo a long and difficult diagnostic journey because of the non-specificity of clinical manifestations and testing methods, resulting in inadequate interventions and delayed diagnosis.8 In a targeted literature review of 23 articles, the median diagnostic delays for ATTRwt-CM and ATTRv-CM were 3.4 and 2.6 years, respectively.9 Furthermore, 34.0–57.0% of patients had previously been misdiagnosed with other cardiac diseases, such as unspecified heart failure (HF), HHD, HCM, HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), and aortic stenosis (AS).9 Delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis of ATTR-CM may result in more advanced disease and poor health-related quality of life at the time of diagnosis, unnecessary tests, and inappropriate treatments.9

To establish the diagnosis of ATTR-CM, it is essential to rule out AL by performing a monoclonal (M) protein test using a serum free light chain (FLC) assay and serum or urine immunofixation (or electrophoresis).1 Invasive (endomyocardial biopsy [EMB] and biopsy of the abdominal wall fat, skin, digestive tract, and lips) and non-invasive (technetium-99 m pyrophosphate [99 mTc-PYP] scintigraphy) techniques can be used to diagnose ATTR-CM.1

Although treatment options for ATTR-CM are limited, there are disease-modifying therapies that stabilize TTR, such as tafamidis. In the Transthyretin Amyloidosis Cardiomyopathy Clinical Trial (ATTR-ACT), a pivotal Phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial, tafamidis reduced all-cause mortality, cardiovascular-related hospitalizations, and declines in functional capacity and quality of life compared with placebo in patients with ATTR-CM.10 Tafamidis was first approved for the treatment of ATTRwt-CM and ATTRv-CM in Japan in 2019.11 In Japan, to be eligible for tafamidis treatment, patients need to have a history of hospitalization for HF or symptoms of HF requiring treatment, biopsy-confirmed amyloid deposits (cardiac or non-cardiac), immunohistochemically confirmed TTR precursor protein, or an end-diastolic interventricular septum thickness >12 mm.1

With the advent of disease-modifying therapies for ATTR-CM, it is becoming increasingly important to evaluate patient journeys. Although there are reports of patient journeys in ATTR-CM from other countries,12,13 data from Japan are limited.14,15 Moreover, evidence for the use of cardiovascular medications in patients with ATTR-CM is sparse.12 Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to describe the journey of Japanese patients from the onset of ATTR-CM-related symptoms to the diagnosis of ATTR-CM. In addition, this study aimed to identify the time lag between the onset of comorbidities indicating the onset of ATTR-CM and the implementation of ATTR-CM-related medical procedures and diagnostic tests and the diagnosis of ATTR-CM, as well as to describe the prescription patterns of cardiovascular drugs in patients with ATTR-CM.

This was a retrospective non-interventional study using the claims database provided by DeSC Healthcare Inc., which contains medical claims data of approximately 12 million insurance subscribers (August 2023). The DeSC Healthcare database is a payer-based database provided by 3 types of Japanese public health insurers: Society-managed, employment-based Health Insurance (SHI) associations; National Health Insurance (NHI); and the Later-Stage Elderly Healthcare System (LSEHS). SHI is provided for individuals working in large companies and their family members. The NHI and SHI cover a broad range of people aged <75 years and those not covered by other public health systems, such as self-employed people, freelancers, farmers, retirees, and college students. In principle, the LSEHS covers people aged ≥75 years and is specifically for insuring elderly individuals. Although the health insurance system switches from the NHI or SHI to the LSEHS when people reach the age of 75 years, data linkage among the NHI, SHI, and LSEHS is not available in the DeSC Healthcare database.

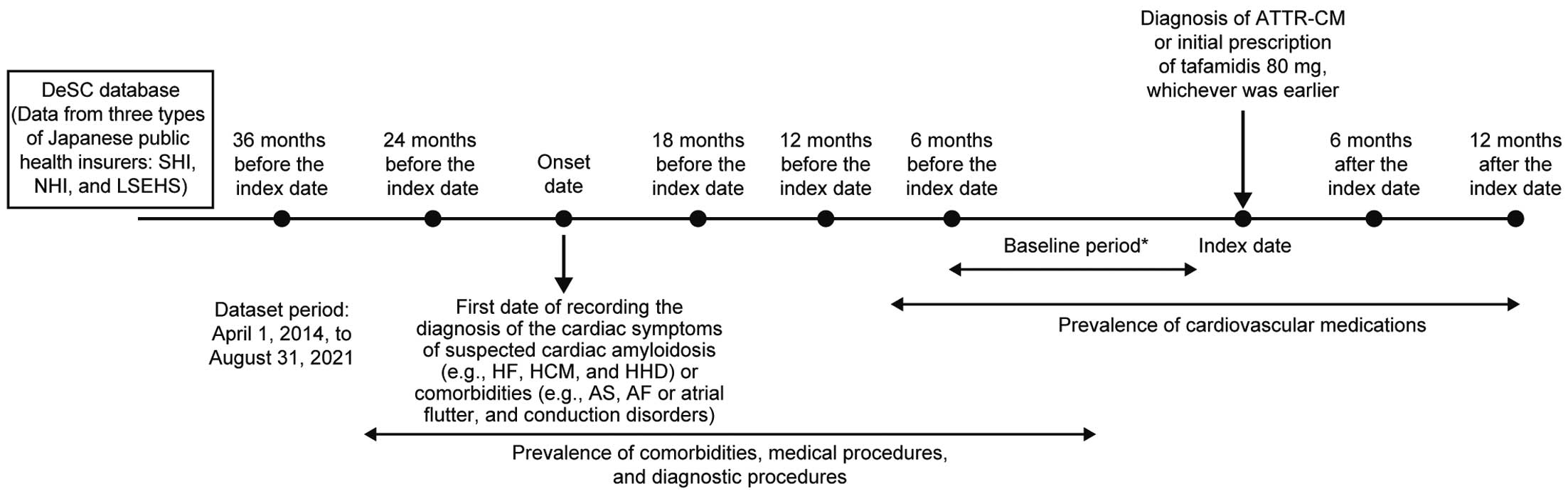

In the present study, we used data from the DeSC Healthcare database between April 1, 2014 and August 31, 2021. We defined the index date as the date when the first diagnosis of ATTR-CM was recorded (excepting diagnoses of “suspected” ATTR-CM) or the date when tafamidis 80 mg was first prescribed, whichever was earlier. The baseline period was defined as the period from the index date to <6 months before the index date. The onset date of ATTR-CM-related symptoms was defined as the date on which a diagnosis of cardiac symptoms of suspected cardiac amyloidosis (e.g., HF, HCM, and HHD) or comorbidities (e.g., AS, AF/atrial flutter, and conduction disorders)5 was first made (Figure 1).

Study design. *Index date–<6 months before the index date. ATTR-CM, transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy; LSEHS, Later-Stage Elderly Healthcare System; NHI, National Health Insurance; SHI, Society-managed, employment-based Health Insurance associations.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MINS (Reference no. MINS-REC-230231). Because the DeSC Healthcare database comprises unlinkable anonymized data, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Eligibility CriteriaPatients were included in the study if they were aged ≥18 years at the index date and had received ≥1 prescription of tafamidis 80 mg or ≥1 of the following ATTR-CM diagnoses, excepting suspected diagnosis, at any time during the study period: ATTR-CM (Japanese claim code: 8850066; International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision [ICD-10] code: E85.4), senile amyloidosis (Japanese claim code: 2773035; ICD-10 code: E85.8), or senile ATTR (Japanese claim code: 8846070; ICD-10 code: E85.8). Patients with a diagnosis of AL amyloidosis (Japanese claim code: 8845844; ICD-10 code: E85.8) or multiple myeloma (MM; Japanese claim code: 2030003; ICD-10 code: C90.0) excepting suspected diagnosis and those who had never received tafamidis 80 mg were excluded.

OutcomesPatient characteristics during the baseline period were recorded. The prevalence of each comorbidity and the implementation of medical and diagnostic procedures related to ATTR-CM in the time period back from the index date (baseline, 6–<12 months before the index date, 12–<18 months before the index date, 18–<24 months before the index date, and 24–<36 months before the index date) and the time lag from the diagnosis of each comorbidity and the implementation of medical and diagnostic procedures to the index date were tracked. The prescription patterns of cardiovascular medications at baseline, 6–<12 months before the index date, from the index date to <6 months after the index date, and 6–<12 months after the index date were also recorded (Figure 1). In addition, patients were divided into 2 groups, namely those prescribed tafamidis 80 mg (tafamidis group) and those diagnosed with ATTR-CM but not prescribed tafamidis 80 mg (non-tafamidis group), and the prevalence of diagnostic procedures related to ATTR-CM, prescription patterns of cardiovascular medications, and the time from the implementation of diagnostic procedures related to ATTR-CM to the index date were evaluated in the 2 groups.

Statistical AnalysisData for all eligible patients were included in the analysis. Data are summarized for the whole study population using descriptive statistics. No imputation was made for missing data. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Of the 11,101,578 patients whose records were available in the DeSC Healthcare database, 246 patients with ATTR-CM met the inclusion criteria; of these, 7 were excluded (2 patients with a diagnosis of AL excepting suspected diagnosis who had never received tafamidis 80 mg and 6 patients with a diagnosis of MM except for suspicious diagnosis who had never received tafamidis 80 mg). Finally, 239 patients were included in the study (tafamidis group: n=139; non-tafamidis group: n=100; Supplementary Figure 1).

Demographics and Baseline Clinical CharacteristicsOf the 239 patients included in the study, 191 (79.9%) were male (Table 1). The proportion of men in the tafamidis and non-tafamidis groups was 95.7% and 58.0%, respectively. In the overall population, the median age of patients was 79.0 years (minimum–maximum 46.0–95.0 years), and 84.1% were from LSEHS. Most patients (42.7%) had their index date in 2020 (tafamidis group: 51.8%; non-tafamidis group: 30.0%). The median age, age distribution, and insurance type were generally similar for the tafamidis and non-tafamidis groups and the overall population. ATTR-CM diagnoses were highest in the year 2020 (42.7%), followed by 2019 (23.0%) and 2021 (19.7%; Supplementary Figure 2). Overall, comorbidities defined as indicating the onset of ATTR-CM were present at baseline in 216 (90.4%) patients, with the most common comorbidity being HF (87.9%), followed by AF/atrial flutter (50.2%), conduction disorders (17.2%), AS (15.5%), HCM (11.3%), and HHD (2.1%; Table 1).

Demographics and Baseline Clinical Characteristics

| All (n=239) |

Tafamidis group (n=139) |

Non-tafamidis group (n=100) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 191 (79.9) | 133 (95.7) | 58 (58.0) |

| Female | 48 (20.1) | 6 (4.3) | 42 (42.0) |

| Age at the index date (years) | 79.0 [46.0–95.0] | 78.0 [49.0–95.0] | 80.0 [46.0–94.0] |

| Age group at index date (years) | |||

| 18–<30 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 30–<40 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 40–<50 | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (2.0) |

| 50–<60 | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.0) |

| 60–<70 | 15 (6.3) | 11 (7.9) | 4 (4.0) |

| 70–<80 | 116 (48.5) | 81 (58.3) | 35 (35.0) |

| ≥80 | 102 (42.7) | 46 (33.1) | 56 (56.0) |

| Insurance type | |||

| SHI | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| NHI | 37 (15.5) | 23 (16.6) | 14 (14.0) |

| LSEHS | 201 (84.1) | 116 (83.5) | 85 (85.0) |

| Comorbidities defined as the onset of ATTR-CM at baselineA | 216 (90.4) | 138 (99.3) | 78 (78.0) |

| HF | 210 (87.9) | 135 (97.1) | 75 (75.0) |

| HHD | 5 (2.1) | 5 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| HCM | 27 (11.3) | 17 (12.2) | 10 (10.0) |

| AF/atrial flutter | 120 (50.2) | 86 (61.9) | 34 (34.0) |

| Conduction disorders | 41 (17.2) | 28 (20.1) | 13 (13.0) |

| Complete AV block | 20 (48.9) | NA | NA |

| AV block | 5 (12.2) | NA | NA |

| Complete LBBB | 4 (9.8) | NA | NA |

| Complete RBBB | 4 (9.8) | NA | NA |

| AS | 37 (15.5) | 25 (18.0) | 12 (12.0) |

Data are presented as the median [range] or n (%). AA patient could have >1 comorbidity defined as the onset of transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) at baseline. AF, atrial fibrillation; AS, aortic stenosis; AV, atrioventricular; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HF, heart failure; HHD, hypertensive heart disease; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LSEHS, Later-Stage Elderly Healthcare System; NA, not available; NHI, National Health Insurance; RBBB, right bundle branch block; SHI, Society-managed, employment-based Health Insurance association.

Time From Appearance of Comorbidities Defined as the Onset of ATTR-CM to Index Date

The median time from the appearance of comorbidities defined as onset of ATTR-CM to the index date was the shortest for AS (5.0 months; interquartile range [IQR] 2.0–16.0 months) and the longest for HF (15.5 months; IQR 5.0–24.5 months; Figure 2). The median (IQR) time, in months, from the diagnosis of AF/atrial flutter, HCM, conduction disorders, and HHD to the index date was 14.0 (IQR 5.0–22.0), 12.0 (IQR 6.5–21.5), 9.0 (IQR 2.0–18.0), and 8.0 (IQR 3.0–25.0), respectively (Figure 2).

Time from the appearance of comorbidities defined as the onset of transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) to the index date. AF, atrial fibrillation; AS, aortic stenosis; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HF, heart failure; HHD, hypertensive heart disease; IQR, interquartile range.

Prevalence of Comorbidities and Implementation of Medical Procedures in Patients With ATTR-CM

The most common comorbidity in patients with ATTR-CM during the observation period was hypertension (71.3–79.9%; Table 2). Cerebrovascular disease, arrhythmia, and ischemic heart disease were reported in 21.1–25.5%, 4.9–11.3%, and 1.8–3.8% of patients, respectively. Extracardiac comorbidities included LSS (23.1–25.5%), neuropathy (4.2–13.0%), CTS (7.5–12.6%), and tendon injury (0.0–0.4%). The frequency of orthopedic diseases, such as CTS and LSS, remained almost unchanged during the study period, whereas that of neuropathy and cardiomyopathy increased (Table 2).

Prevalence of Comorbidities and Medical Procedures in Patients With Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy

| 24–<36 months before index date |

18–<24 months before index date |

12–<18 months before index date |

6–<12 months before index date |

Baseline (index date–<6 months before index date) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients | 109 | 143 | 175 | 188 | 239 |

| Comorbidities | 92 (84.4) | 119 (83.2) | 156 (89.1) | 166 (88.3) | 229 (95.8) |

| Arrhythmia | 8 (7.3) | 7 (4.9) | 17 (9.7) | 18 (9.6) | 27 (11.3) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 12 (11.0) | 19 (13.3) | 52 (29.7) | 80 (42.6) | 162 (67.8) |

| CTS | 9 (8.3) | 15 (10.5) | 22 (12.6) | 16 (8.5) | 18 (7.5) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 24 (22.0) | 32 (22.4) | 37 (21.1) | 41 (21.8) | 61 (25.5) |

| Hypertension | 78 (71.6) | 102 (71.3) | 128 (73.1) | 143 (76.1) | 191 (79.9) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2 (1.8) | 3 (2.1) | 6 (3.4) | 6 (3.2) | 9 (3.8) |

| LSS | 26 (23.9) | 33 (23.1) | 44 (25.1) | 48 (25.5) | 57 (23.9) |

| Neuropathy | 6 (5.5) | 6 (4.2) | 10 (5.7) | 11 (5.9) | 31 (13.0) |

| Tendon injury | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Medical procedures | 57 (52.3) | 78 (54.6) | 120 (68.6) | 139 (73.9) | 214 (89.5) |

| Ablation | 2 (1.8) | 2 (1.4) | 2 (1.1) | 4 (2.1) | 6 (2.5) |

| Biochemical tests | 45 (41.3) | 68 (47.6) | 104 (59.4) | 129 (68.6) | 210 (87.9) |

| Cardiac MRI | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) | 9 (5.1) | 13 (6.9) | 39 (16.3) |

| Carpal tunnel release surgery | 3 (2.8) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.3) |

| Echocardiography | 30 (27.5) | 39 (27.3) | 72 (41.1) | 97 (51.6) | 185 (77.4) |

| Holter echocardiography | 4 (3.7) | 5 (3.5) | 17 (9.7) | 11 (5.9) | 34 (14.2) |

| Pacemaker | 6 (5.5) | 8 (5.6) | 11 (6.3) | 17 (9.0) | 45 (18.8) |

| SAVR/TAVI | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.6) | 4 (1.7) |

Unless indicated otherwise, data are presented as n (%). CTS, carpal tunnel syndrome; LSS, lumbar spinal stenosis; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Overall, the frequency of medical procedures for comorbidities associated with ATTR-CM increased from 24–<36 months before the index date to baseline (Table 2). The most common procedures were biochemical tests (41.3–87.9%), followed by echocardiography (27.3–77.4%) and Holter echocardiography (3.5–14.2%). The use of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) increased from 0.9% during the period 24–<36 months before the index date to 16.3% at baseline. Ablation, carpal tunnel release surgery, pacemaker implantation, and surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR)/transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) were performed in 1.1–2.5%, 0.5–2.8%, 5.5–18.8%, and 0.9–1.7% of patients, respectively (Table 2).

Time From Appearance of Each Comorbidity and Implementation of a Medical Procedure to the Index DateThe median time from the diagnosis of a comorbidity to the index date was the shortest for tendon injury (3.0 months; IQR 3.0–3.0 months) and the longest for hypertension (20.5 months; IQR 7.0–31.0 months; Figure 3A). The median time from the first medical procedure to the index date was the shortest for pacemaker implantation (4.0 months; IQR 2.0–16.0 months) and the longest for SAVR/TAVI (16.5 months; IQR 9.5–24.0 months; Figure 3B).

Time to the index date from the onset of (A) comorbidities and (B) medical procedures. *Four or fewer patients at baseline. CTS, carpal tunnel syndrome; IQR, interquartile range; LSS, lumbar spinal stenosis; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Frequency of Diagnostic Procedures Related to ATTR-CM

At baseline, 99 mTc-PYP scintigraphy, the M protein test, biopsy, and genetic testing were performed in 33.1%, 37.7%, 34.7%, and 28.9% of patients, respectively (Table 3). Of the patients who underwent biopsy, the proportion of patients who underwent EMB increased over time, ranging from 12.5% to 78.3%. Among patients in whom the M protein test was performed, FLC+serum+urine and FLC-only tests were performed in 18.0% and 4.6% of patients, respectively, at baseline. At baseline, compared with the overall population, the proportion of patients undergoing a diagnostic procedure was higher in the tafamidis group and lower in the non-tafamidis group (58.6% vs. 64.0% and 51.0%, respectively; Supplementary Tables 1,2). Moreover, the proportion of patients who underwent the M protein test, biopsy, genetic testing, and EMB at baseline was higher in the tafamidis group than in the overall population (Supplementary Table 1).

Prevalence of Diagnostic Procedures Related to Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy

| 24–<36 months before index date |

18–<24 months before index date |

12–<18 months before index date |

6–<12 months before index date |

Baseline (index date–<6 months before index date) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients | 109 | 143 | 175 | 188 | 239 |

| Diagnostic procedures | 13 (11.9) | 7 (4.9) | 25 (14.3) | 55 (29.3) | 140 (58.6) |

| 99 mTc-PYP scintigraphy | 4 (3.7) | 2 (1.4) | 9 (5.1) | 26 (13.8) | 79 (33.1) |

| M protein test | 2 (1.8) | 3 (2.1) | 10 (5.7) | 30 (16.0) | 90 (37.7) |

| FLC-only | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (1.6) | 11 (4.6) |

| FLC+serum+urine | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.1) | 7 (3.7) | 43 (18.0) |

| BiopsyA | 8 (7.3) | 4 (2.8) | 20 (11.4) | 37 (19.7) | 83 (34.7) |

| EMBB | 1 (12.5) | 1 (25.0) | 9 (45.0) | 22 (59.5) | 65 (78.3) |

| Genetic testing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 13 (6.9) | 69 (28.9) |

Unless indicated otherwise, data are presented as n (%). ABiopsies were performed at several sites and included percutaneous needle biopsy, endoscopic biopsy (per organ), bone marrow biopsy, percutaneous renal biopsy, and tissue sampling using the excision method (peripheral nerve, oral cavity, skin, heart muscle, and muscles). BEndomyocardial biopsy (EMB) is also included under biopsy, with the denominator being the number of patients who underwent a biopsy. 99 mTc-PYP, technetium-99 m pyrophosphate; FLC, free light chain; M protein, monoclonal protein.

Time From Implementation of Diagnostic Procedures Related to ATTR-CM to the Index Date

The median time, in months, from the implementation of genetic testing, 99 mTc-PYP scintigraphy, EMB, the M protein test, and biopsy to the index date was 4.0 (IQR 2.0–6.0), 5.0 (IQR 2.0–8.0), 5.0 (IQR 3.0–8.0), 5.0 (IQR 3.0–8.0), and 7.0 (IQR 4.0–12.5), respectively (Figure 4). Compared with the overall population, the median time from the implementation of any diagnostic procedure related to ATTR-CM to the index date was similar in the tafamidis group but shorter in the non-tafamidis group (Supplementary Figure 3).

Time from the implementation of diagnostic procedures related to transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy to the index date. Biopsies were performed at several sites and included percutaneous needle biopsy, endoscopic biopsy (per organ), bone marrow biopsy, percutaneous renal biopsy, and tissue sampling using the excision method (peripheral nerve, oral cavity, skin, heart muscle, and muscles). Endomyocardial biopsy is also included. 99 mTc-PYP, technetium-99 m pyrophosphate; IQR, interquartile range; M protein, monoclonal protein.

Prescription of Cardiovascular Medications

Across time points, diuretics (52.1–67.4%) were the most commonly prescribed drug class, followed by mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs; 31.4–47.7%). Anticoagulants, β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), digoxin, and amiodarone were prescribed to 39.4–48.5%, 24.3–30.5%, 13.8–17.6%, 4.3–9.5%, 2.5–4.8%, and 4.8–10.7% of patients, respectively (Table 4). The proportion of patients prescribed angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)/angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) and calcium channel blockers successively decreased from baseline to 6–<12 months after the index date. The prescription patterns for the tafamidis and non-tafamidis groups are presented in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4.

Prescription of Cardiovascular Medications in Patients With Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy

| 6–<12 months before index date |

Baseline (index date–<6 months before index date) |

Index date–<6 months after index date |

6–<12 months after index date |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients | 188 | 239 | 239 | 169 |

| Medications | ||||

| ACEi | 26 (13.8) | 40 (16.7) | 42 (17.6) | 28 (16.6) |

| ARB/ARNIs | 67 (35.6) | 77 (32.2) | 72 (30.1) | 42 (24.9) |

| β-blockers | 53 (28.2) | 73 (30.5) | 63 (26.4) | 41 (24.3) |

| MRAsA | 59 (31.4) | 114 (47.7) | 113 (47.3) | 71 (42.0) |

| SGLT2i | 8 (4.3) | 18 (7.5) | 20 (8.4) | 16 (9.5) |

| Diuretics | 98 (52.1) | 161 (67.4) | 160 (67.0) | 106 (62.7) |

| CCBs | 59 (31.4) | 70 (29.3) | 60 (25.1) | 31 (18.3) |

| Digoxin | 9 (4.8) | 6 (2.5) | 7 (2.9) | 6 (3.6) |

| Amiodarone | 9 (4.8) | 19 (8.0) | 18 (7.5) | 18 (10.7) |

| Anticoagulants | 74 (39.4) | 111 (46.4) | 116 (48.5) | 81 (47.9) |

Unless indicated otherwise, data are presented as n (%). AMineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) have diuretic properties; however, because they also have cardioprotective properties, they were not included in the diuretic category in this study and were analyzed separately. ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor; CCBs, calcium channel blockers; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors.

This real-world study highlights the journey of Japanese patients with ATTR-CM and time lag from the onset of clinical manifestations of ATTR-CM to its diagnosis. Comorbidities such as HHD, HCM, AS, conduction disorders, AF/atrial flutter, and HF were defined as the onset of ATTR-CM. Extracardiac symptoms included LSS, CTS, and neuropathy. The findings of this study suggest a time lag between the onset of the first comorbidities suggestive of ATTR-CM and the implementation of diagnostic procedures for ATTR-CM in Japanese patients, emphasizing the need for early diagnosis and access to disease-modifying treatments such as tafamidis to improve patient outcomes.

The study population primarily comprised elderly men, aligning with other real-world studies of ATTR-CM.8,12 The proportion of women was higher in the non-tafamidis than tafamidis group (42.0% vs. 4.3%, respectively), which may be attributed to the slightly higher median age in the former group (80.0 vs. 78.0 years, respectively). Although tafamidis was approved for the treatment of patients with ATTR-CM in Japan in 2019, approximately 30% of patients did not receive the drug (non-tafamidis group), suggesting that the diagnosis of ATTR-CM is often delayed or that it is misdiagnosed due to morphological similarities with other cardiac diseases, such as HCM and HF.13,16 In a real-world study conducted in Japan from June 2019 to July 2021, tafamidis treatment was initiated in approximately 50% of patients with ATTR-CM, and the most common reason for the non-administration of tafamidis was advanced HF, followed by the patient’s frailty.17 Early stages of ATTR-CM manifest as HFpEF and may mimic HHD or HCM. A diagnosis of HHD does not exclude the possibility of ATTR-CM.18 In the present study, HF was the most common comorbidity defined as the onset of ATTR-CM (87.9%), which is in agreement with the findings of other studies,8,16 and the median time from diagnosis to the index date was 15.5 months. In a multicenter, prospective, observational study conducted in Japan from September 2018 to January 2022, 14.2% of patients with HFpEF showed positive cardiac uptake on 99 mTc-PYP scintigraphy.19

In the present study, 2.1%, 11.3%, 15.5%, 17.2%, and 50.2% of patients had HHD, HCM, AS, conduction disorders, and AF/atrial flutter (defined as the onset of ATTR-CM) at baseline, respectively, with corresponding median times from diagnosis to the index date of 8.0, 12.0, 5.0, 9.0, and 14.0 months. In the present study, the prevalence of AF (47.0% vs. 50.2%) and AS (6.0% vs. 15.5%) was higher than reported in another study from Japan.14 Although it is unclear whether ATTR-CM was appropriately suspected in clinical practice at the time due to the presence of comorbidities such as AS, AF, and conduction disorders, the fact that a certain number of patients in the present study had these comorbidities among those who were ultimately diagnosed with ATTR-CM and that the onset of comorbidities precedes the timing of diagnosis suggests that, in the future, the diagnosis of ATTR-CM will have to be made considering the presence/absence of these comorbidities. Considering the spectrum of clinical presentations of patients with ATTR-CM, an appropriate diagnosis is necessary to ensure timely treatment.

In patients with early-stage arrhythmia, ablation may help maintain sinus rhythm, especially in patients with atrial flutter.3 In the present study, ablation had been performed in 2.5% of patients with ATTR-CM at baseline. Up to one-third of patients with ATTR-CM and conduction disturbances require permanent pacemakers.3 In the present study, at baseline 18.8% of patients had undergone pacemaker implantation, and the median time from implementation of the procedure to the index date was 4.0 months. AS is more common in older people, and patients often present with an asymptomatic but severe form of the condition.20 SAVR/TAVI is the preferred treatment approach for AS.21 In the present study, 1.7% of patients had undergone SAVR/TAVI at baseline, and the median time from SAVR/TAVI to the index date was 16.5 months. The number of SAVR cases was quite small (n=4), which may explain the apparent discrepancy in the time from diagnosis of AS and SAVR/TAVI to the index date.

The frequent association of ATTR-CM with CTS, LSS, and tendon injury is well established, and their onset usually precedes the diagnosis of ATTR-CM.22 CTS has been reported in approximately 40–50% of patients with ATTR-CM.13,14 However, in the present study, CTS was present in only 7.5% of patients at baseline, which may be attributed to the fact that the diagnosis of CTS was made at the time of carpal tunnel release surgery, rather than being based only on numbness in the hands. Overall, at baseline 1.3% of patients had undergone carpal tunnel release surgery, and the median time from its implementation to the index date was 13.0 months. In a Danish study, screening for ATTR-CM in patients who had received prior surgery for bilateral CTS identified approximately 5% of patients with early-stage ATTR-CM.23 In an observational study conducted in Japan, patients with systemic ATTRwt amyloidosis were stratified into CTS-onset and cardiac-onset groups.24 In the CTS-onset group, CTS preceded cardiac symptoms by 1–14 years, suggesting that CTS could be an initial symptom of systemic ATTRwt amyloidosis in some patients.24 LSS has been associated with the deposition of ATTR, which causes thickening of the ligamentum flavum, leading to compression and narrowing of the spinal canal.3 In the present study, LSS was present in 23.9% of patients at baseline, and the median time from diagnosis to the index date was 19 months, which is shorter than that reported in a systematic review (approximately 2–7.4 years before ATTRwt diagnosis).26

EMB remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of ATTR-CM and has a sensitivity and specificity of nearly 100%, provided biopsy specimens are collected from multiple sites (≥4 are recommended) and tested for amyloid deposits by Congo red staining.1,25 In the present study, 34.7% of patients at baseline underwent biopsies, 78.3% of which were EMB. The median time from the implementation of these procedures to the index date was 7.0 months for a biopsy and 5.0 months for an EMB. 99 mTc-PYP scintigraphy scans are non-invasive and reliable for the diagnosis of ATTR-CM.1,27 In the present study, 99 mTc-PYP scintigraphy was performed in 33.1% of patients at baseline, and the median time from its implementation to the index date was 5.0 months. Despite 99 mTc-PYP scintigraphy being an effective diagnostic tool, its limited use in the present study (33.1%) may be attributed to restricted availability, the need for specialized centers, and the relatively high cost.28 Moreover, 99 mTc-PYP scintigraphy as a diagnostic method was approved by the Japanese National Health Insurance Reimbursement Authority in October 2020,29 and it was only recently added to the diagnostic algorithms in the Japanese Circulation Society guidelines,1 which may have further contributed to its limited utilization. Furthermore, in Japan, a biopsy is mandatory for prescribing tafamidis,1 which could have also contributed to the relatively lower use of 99 mTc-PYP scintigraphy. Considering the utility of 99 mTc-PYP scintigraphy in diagnosing ATTR-CM in the real-world setting, it should be routinely used for diagnosis in patients in whom ATTR-CM is suspected.30

In patients in whom AL is excluded, the diagnostic specificity and positive predictive value of the M protein text for ATTRwt-CM are both 100%.1 Genetic testing for the TTR gene provides a definitive diagnosis of ATTRv-CM and ATTRwt-CM.1 However, in the present study, the genetic testing was not specific for TTR and may have included tests for other cardiomyopathies. Therefore, it is possible that the genetic testing was performed long before the index date (diagnosis of ATTR-CM or start of tafamidis prescription). This may have contributed to a delay in the implementation of genetic testing for ATTR-CM diagnosis from the index date. Moreover, the delay in diagnosis may also be explained by a low level of disease awareness among physicians.31

Instead of initiating treatment with disease-modifying therapies that can prevent disease progression, clinicians generally initiate symptomatic treatment in patients with ATTR-CM for cardiac manifestations such as HF (e.g., ACEi, ARBs, ARB/ARNIs, β-blockers, MRAs, diuretics, digoxin, and SGLT2i) and arrhythmias (e.g., amiodarone).1 ACEi, ARBs, and ARNIs are poorly tolerated, and data specific to ATTR-CM are limited.32 Beta-blockers, even at low doses, may be poorly tolerated and should be used with caution in patients with ATTR-CM.32,33 The proportion of patients prescribed diuretics at baseline in the present study was lower than that in another study from the UK (62.7% vs. 82.4%, respectively).34 MRAs were prescribed to 42.0% of patients at baseline, comparable to the rate reported in the UK study (39.0%).34 Digoxin has been contraindicated in patients with cardiac amyloidosis because the usual daily dose could cause life-threatening arrhythmia.1 Recent studies have shown that digoxin may be a therapeutic option for rate and symptom control in some patients with AL and cardiac ATTR; however, rigorous patient selection is recommended, and patients should be closely monitored during digoxin administration.35 SGLT2i have shown beneficial effects in patients with HFpEF; however, there is limited evidence on their use in patients with ATTR-CM.32,36 Amiodarone is the preferred antiarrhythmic agent in patients with ATTR-CM because of its favorable safety profile in cardiomyopathy; however, safety data are limited.3 In the present study, amiodarone was prescribed to approximately 5–10% of patients, and anticoagulant therapy was prescribed to approximately 40–50% of patients. According to Japanese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cardiac amyloidosis, anticoagulants should be prescribed for all patients with cardiac amyloidosis accompanied by AF, atrial tachycardia, and systolic/diastolic dysfunction after evaluation of the bleeding risk.1

The strengths of this study are that the findings are based on the DeSC Healthcare database, which covers patients of all ages, can follow all claims even if patients visit multiple medical facilities (unless they withdraw the health insurance), and is more suitable for longitudinal studies and tracing data for elderly patients to facilitate understanding of the journey of patients with ATTR-CM.

Study LimitationsFirst, because all individuals are transferred to LSEHS at the age of 75 years, data of patients with an index date in the LSEHS could not be traced back to their data before age 75 years. In addition, the database period was short in 2014 (starting from April 1, 2014) and 2021 (up until August 31, 2021). Furthermore, if a patient had changed their insurance system, they could be counted twice because patient data linkage was not possible. Second, the evaluation was based on the disease name of the insurance claim, and certain diseases could have been underestimated depending on what was entered in the database. Third, although information on clinical testing and procedures was available in the database, biochemical test results for specific biomarkers (e.g., B-type natriuretic peptide) and echocardiography were not available, and genetic testing did not include genetic testing only for TTR; therefore, it was not possible to examine any association between delayed diagnosis and the severity of ATTR-CM. Fourth, due to limitations of the study database, it was not possible to distinguish between HFpEF and HF or to draw any conclusions regarding trends in diagnostic variability between the different regions of Japan. Finally, although diagnoses of cardiac symptoms related to ATTR-CM were defined as the onset of ATTR-CM, it remains uncertain whether a diagnosis of ATTR-CM was suspected due to these comorbidities.

This study highlighted the types of comorbidities associated with ATTR-CM and revealed the delays between the appearance of these comorbidities and the implementation of each procedure related to ATTR-CM in a Japanese clinical setting. Diuretics were the most widely prescribed drug class, followed by MRAs. The findings of this study suggest the need for the early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of ATTR-CM.

Medical writing support was provided by Sarayu Pai, PhD, CMPP, of Cactus Life Sciences (part of Cactus Communications) and funded by Pfizer Japan Inc.

This study was supported by Pfizer Japan Inc.

M.M. has received lecture fees from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co. Ltd., manuscript fees from Pfizer Japan Inc., and research funding from JSPS KAKENHI 22K16099, and is a member of the Advisory Board for Pfizer Japan Inc. H.K., Y.K., and K.T. are employees of Pfizer Japan Inc. H.A. was an employee of Pfizer Japan Inc. at the time the study was conducted. Y.I. has received lecture fees from Pfizer Japan Inc., Daiichi Sankyo Company Limited, and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, manuscript fees from Pfizer Japan Inc., and is a member of the Advisory Board for Pfizer Japan Inc.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MINS (a non-profit Research Ethics Review Committee meeting) (MINS-REC-230231).

Please find supplementary file(s);

https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-24-0666