論文ID: CJ-25-0668

論文ID: CJ-25-0668

To achieve early reperfusion in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), several time-based metrics have been introduced to reduce the total myocardial ischemic time from symptom onset to reperfusion. Among these, the door-to-device interval has served as an indicator of time efficiency of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)-capable hospitals in STEMI treatment, with prior studies reporting progressive improvements.1 Additionally, the first medical contact-to-device interval (FMC2D) has been recognized as a more comprehensive metric reflecting regional coordination across prehospital and in-hospital systems. The 2018 Japanese Circulation Society guideline2 and the 2025 American Heart Association guidelines3 recommend achieving an FMC2D <90 min. The 2023 European Society of Cardiology guideline4 further recommends a target of <90 min when ST-elevation is identified by an emergency medical service (EMS) or at a non-PCI-capable hospital and <60 min when identified at a PCI-capable hospital. Furthermore, EMS-obtained prehospital ECGs are effective for the early recognition and triage of STEMI.5 These ECGs enable direct transport to PCI-capable hospitals, facilitate early activation of the catheterization team, and may allow bypassing the emergency department (ED) or omitting repeat ECG acquisition in the ED.6 These measures collectively contribute to reducing the time to reperfusion.

Article p ????

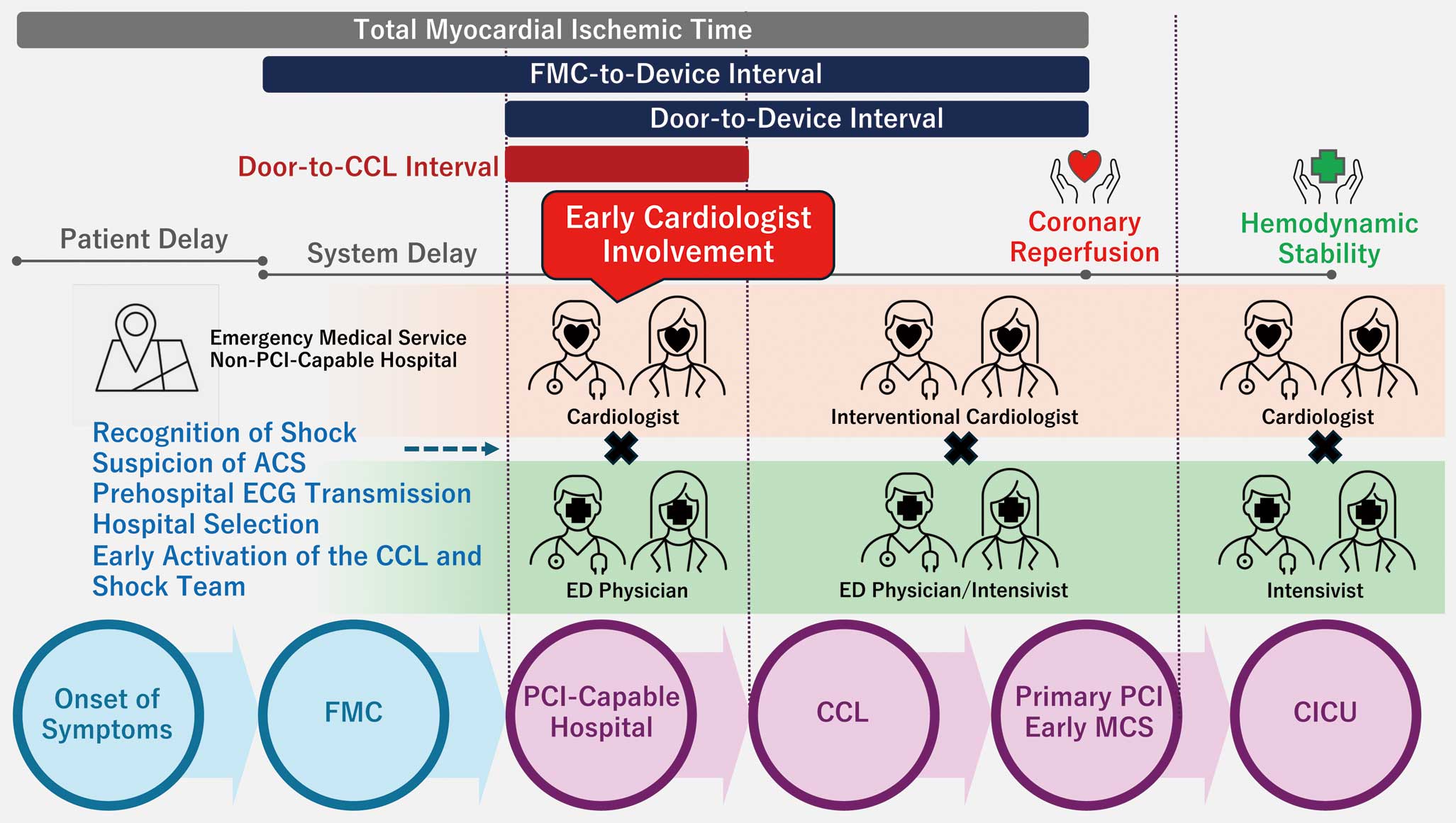

In combination with advances in PCI techniques and antithrombotic therapy, these time-sensitive strategies have contributed to improved outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) without shock (Figure).7 However, additional considerations are required in patients with AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock (AMI-CS), to simultaneously rescue the at-risk myocardium through primary PCI and prevent end-organ damage by achieving early hemodynamic stabilization. The latter often requires early initiation of mechanical circulatory support (MCS), particularly in cases refractory to vasopressors or inotropes.

Time-sensitive management pathway for patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CCL, cardiac catheterization laboratory; CICU, cardiac intensive care unit; ECG, electrocardiogram; ED, emergency department; FMC, first medical contact; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

In this issue of the Journal, Ko et al. analyze data from the K-ACTIVE registry, comprising 369 patients with AMI-CS, admitted to 52 PCI-capable hospitals.8 They focus on an underexplored in-hospital time metric: the door-to-catheterization laboratory interval (D2C), using it as a surrogate marker for system efficiency and triage effectiveness in the time management of AMI-CS. The group with shorter D2C times (≤39 min) had a significantly lower in-hospital mortality rate than the longer D2C group (>39 min), with mortality rates of 18.8% and 37.6%, respectively. In their multivariable analysis, shorter D2C was independently associated with the presence of first contact by a cardiologist, chest pain, lower heart rates, and lower serum creatinine levels at admission. Early cardiologist involvement may facilitate procedural planning, frontline recognition, and triage in patients with AMI-CS.

However, this study has several limitations. First, it did not incorporate standardized classifications of shock severity, such as the Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions staging system,9 and lacked detailed information on initial treatments administered in the ED or the temporal progression of shock. Given that collaborative models between ED physicians and cardiologists, and the ED’s capacity to manage shock, likely varied across participating institutions, the actual interventions delivered during D2C remain unclear and may have been heterogeneous. Second, the extent to which prehospital information was utilized in early patient management remains unclear. The contribution of prehospital EMS-provided data, such as prehospital ECGs or vital signs, to initial clinical decision-making remains unclear. Third, patients in the shorter D2C group may have been less critically ill. As the authors noted, the longer D2C group included more patients who experienced out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. In such cases, necessary interventions in the ED, such as intubation, mechanical ventilation, or computed tomography imaging to evaluate for intracranial hemorrhage, neurological damage, or thoracic trauma from chest compressions, could have delayed D2C. Furthermore, the shorter D2C group had lower heart rates and serum creatinine levels on admission, both of which may suggest lower baseline illness severity. Fourth, the hemodynamic phenotype of shock was not reported. Hemodynamic presentations in AMI-CS are often heterogeneous,10 and cases involving vasodilatory or mixed shock may require additional delay to differentiate CS from other shock etiologies.

Only 34% of patients in this study achieved an FMC2D within 90 min, highlighting the logistical and clinical challenges of time-sensitive management in AMI-CS. Nevertheless, early cardiologist involvement was associated with shorter D2C, which provides important insights for optimizing future CS care. Early cardiologist engagement may promote early recognition and accurate triage of CS and early initiation of MCS and PCI, all of which can potentially improve clinical outcomes. We strongly emphasize that cardiologists should not wait to be called by ED physicians, but should instead establish systems that enable collaboration from the moment a patient’s transport is arranged. This concept aligns with the expert consensus released by the Japan Critical Care Cardiology Committee.11 In managing CS, the ability to balance both speed and quality in clinical decision-making across the prehospital setting, ED, cardiac catheterization laboratory, and cardiac intensive care unit will be increasingly essential.

None.