2019 Volume 67 Issue 9 Pages 977-984

2019 Volume 67 Issue 9 Pages 977-984

Endomorphin-1 (Tyr-Pro-Trp-Phe-NH2, EM-1), an endogenous μ-opioid receptor ligand with strong antinociceptive activity, is not in clinical use because of its limited metabolic stability and membrane permeability. In this study, we develop a short-peptide self-delivery system for brain targets with the capability to deliver EM-1 without vehicle. Two amphiphilic EM-1 derivatives, C18-SS-EM1 and C18-CONH-EM1, were synthesized by attaching a stearyl moiety to EM-1 via a disulfide and amide bond, respectively. The amphiphilicity of EM-1 derivatives enabled self-assembling into nanoparticles for brain delivery. The study assessed morphology, circular dichroism, and metabolic stability of the formulations, as well as their pharmacodynamics and in vivo distribution, directly monitored by near-IR fluorescence imaging in mouse brains. In aqueous solution, the C18-SS-EM1 derivative self-assembled into spherical nanostructures with a diameter of 10–20 nm. Near-IR fluorescence analysis visualized the accumulation of the peptides in the brain. Importantly, the analgesic effect of C18-SS-EM1 nanoparticles was significantly stronger as compared to that of unmodified EM-1 or C18-CONH-EM1 nanoparticles. An in vitro release study demonstrated that self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 nanoparticles possessed reduction-responsive behavior. In summary, self-assembling C18-SS-EM1 nanoparticles, which integrate the advantages of lipidization, nanoscale characteristics and, labile disulfide bonds, represent a promising strategy for brain delivery of short peptides.

Delivery of therapeutic peptides to the central nervous system (CNS) represents a challenge and is the subject of neuropharmaceuticals research. The most critical factor limiting peptide delivery is the protective function of the blood–brain barrier (BBB). The BBB consists of the endothelial cells in brain capillaries that form tight junctions, which control the concentration and entry of drugs into the CNS.1) In addition, low metabolic stability of peptides represents a serious liability that restricts their accumulation in the brain, which reduces their bioavailability or their ability to exert an adequate intrinsic activity.2) Many peptides are potential neuropharmaceuticals including amyloid beta aggregation inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease,3) peptides for Parkinson’s disease,4) and analgesic opioid peptides.5) Endomorphin-1 (Tyr-Pro-Trp-Phe-NH2, EM-1) and endomorphin-2 (Tyr-Pro-Phe-Phe-NH2, EM-2), isolated from the bovine brain and, subsequently, from the human brain cortex,6–8) are two μ-opioid receptor (MOR) agonists with improved affinity and selectivity. Both EM-1 and EM-2 have a wide range of physiological and pharmacological effects, among which the antinociceptive activity is the most interesting.9,10) However, similar to other neuropeptides, EMs remain undeveloped as clinically viable drugs for the treatment of pain because of the delivery challenges including exclusion from the brain and degradation within the blood.

Over the last two decades, a considerable number of strategies for the transport of therapeutic molecules across the BBB have been proposed and tested in preclinical and clinical trials.4,11) Among them, nanocarriers have shown their potential to deliver drugs across the BBB due to their notable properties such as tiny size and an easily tailored surface.4,12,13) However, there are still some challenges including low drug loading capacity resulting from the polymers with high molecular weight, poor reproducibility of dual- or multi-functional modifications and the potential long-term toxicity of synthetic nanomaterials.

Recently, scientists proposed a new concept for a drug self-delivery system that uses the drugs as materials to build a nanosystem. For example, hydrophobic anticancer drugs were stimulated to self-assemble into diverse nanostructures by direct conjugation to a short peptide,14,15) a short oligomeric ethylene glycol16) or small organic molecules.17) This amphiphilic self-assembling drug–drug conjugation strategy has attracted much attention as a promising approach to achieve improved drug loading capacity, fewer side effects caused by carriers and passive target properties in drug delivery. Peptides, due to their unique secondary structures, have the intrinsic ability to form self-assembling nanostructures by intermolecular hydrogen bonding18,19) as an advantage over conventional small organic drugs in drug–drug conjugate delivery systems. In addition, the self-assembled short-peptide-based nanostructures have many beneficial properties, such as high synthesis yields, stability, flexibility, inherent biocompatibility and biodegradability.20) Mazza’ group reported the direct conjugation of dalargin, a leucine-enkephalin analog, to a palmitoyl moiety via an ester link.21) The resulting amphiphilic peptide could form nanofibers with high drug loading capacity and remarkably improved BBB permeability.

Disulfide bonds have been extensively used as reduction-responsive linkers in brain targeted drug delivery because of their susceptibility to a reductive environment and the rapid cleavage by reducing agents such as glutathione (GSH).22–24) In our previous study, we also confirmed that, as compared to amide and maleimide, the disulfide bond was the most efficient linkage to promote endomorphin-1 translocation across the BBB due to its reductive effect.25) Importantly, disulfide bonds play a significant role in the folding and aggregation of peptides and proteins,26) which potentially can promote self-assembling. Wang et al. also proved that a disulfide bond could balance the competition between intermolecular forces, suggesting that its insertion into molecules could promote and stabilize the self-assembling of nanomedicines.27)

In this report, we synthesized two amphiphilic EM-1 derivatives, C18-SS-EM1 and C18-CONH-EM1, by covalently linking a stearyl moiety to the opioid peptide EM-1 via a disulfide and amine bond, respectively, to stimulate self-assembling into nanoparticles (NPs). We profiled the in vitro properties of the novel EM-1 derivatives, studied their pharmacodynamics in a mouse model, and directly monitored the drug distribution profile in the mouse brain.

All fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc)-protected amino acids are of the L-form and all were obtained from GL Biochem Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBT) O-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) were also purchased from GL Biochem Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Rink Amide MBHA resin (0.45 mmol/g) were obtained from Nankai Hecheng S&T Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). A near-infrared (NIR) dye, 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindotricarbocyanine iodide (DiR), was purchased from Fanbo Biochemicals Ltd. (Beijing, China). All other reagents and chemicals were obtained from J&K Scientific Ltd. (Beijing, China).

AnimalsMale Kunming mice (18–22 g) supplied by the Animal Center at the Medical College of Lanzhou University (Gansu, China) were used in the analgesia studies. Adult Balb/c male nude mice (8 weeks of age) purchased from the Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) were used in the NIR fluorescence studies. All animal experiments were performed according to the principles and guidelines of the Ethics Committee at Lanzhou University.

Synthesis of EM-1 ConjugatesTwo different EM-1 conjugates were synthesized by forming covalent linkages via an amide or a disulfide bond.

Synthesis of C18-SS-EM1The synthesis of stearic acid containing a disulfide was performed as described previously.27) Briefly, dithiodiglycolic acid was induced to form the corresponding anhydride using acetic anhydride as a dehydration agent. Excessive acetic anhydride was removed using a rotary evaporation apparatus at 30°C. The residue was reacted with stearyl alcohol, using 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) as a catalyst to expedite product formation.

The EM-1 peptide was synthesized by standard solid-phase peptide synthesis using Fmoc chemistry. The stearic acid containing disulfide was used as Fmoc amino acid and attached to the N-terminus of EM-1. The resulting EM-1 derivative C18-SS-EM1 was cleaved in a mixture of trifluoroacetic acid–triisopropylsilane–water at a ratio of 95 : 2.5 : 2.5 for 3 h at room temperature.

Synthesis of C18-CONH-EM1The amide-linked derivative C18-CONH-EM1 was assembled following the conventional Fmoc-based solid-phase method. Stearic acid was coupled to the N-terminus of EM-1 as Fmoc amino acid.

All crude peptide derivatives were purified and analyzed by reversed-phase (RP)-HPLC (Waters 1525, Waters) on a C18 column. The molecular mass was determined by electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS.

Self-assembly and CharacterizationSelf-assembly of the nanomedicines was performed according to the nanoprecipitation method.27) Briefly, the EM-1 derivatives were dissolved in ethanol and added dropwise to deionized water over 30 min, under mechanical stirring (approx. 600–800 rpm) at room temperature. The final ethanol concentration was maintained at 2–5% and the self-assembly occurred spontaneously under these conditions.

The shape and morphology were visualized and imaged by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL, Japan). The particle sizes, zeta potential, and polydispersity index (PDI) of self-assembled nanomedicines were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern, U.K.). The concentration of the solution was 10 µmol/L and each sample analysis was carried out in triplicate.

Circular Dichroism (CD) MeasurementsThe CD measurements of the C18-CONH-EM1 and C18-SS-EM1 NPs were performed on a CD spectropolarimeter (JASCO, J-810) using a quartz cell with a 1.0 mm path length. The concentration of the solution was 50 µmol/L for CD measurements. The CD spectra were obtained with solvent subtraction from 190 to 260 nm at a 10 nm·min−1 scan rate and were averaged from five repeat scans per sample. The obtained CD spectral intensity is presented as the mean molar ellipticity per residue (deg·cm2·dmol−1·residue−1). For secondary structure determination, samples were analyzed in the range of 190–240 nm to derive the content of α-helix (%) and β-strand (%) using k2d3 software, a package freely available online (http://www.ogic.ca/projects/k2d3).

Metabolic Stability StudiesMetabolic stability of EM-1 and its self-assembled nanomedicines was assessed in mouse serum and brain homogenate. Fresh plasma and 15% mouse brain homogenate were prepared as described previously.28) The amounts of remaining intact peptides were determined by RP-HPLC. Briefly, approximately 10 µL of self-assembled nanomedicine solution (2 mmol/L) was incubated in 190 µL test or control solution at 37°C. At designated time points (0, 10, 30, 60, 120, 240, 480 min), 20 µL aliquots were removed from the samples and immediately mixed with 90 µL of acetonitrile to precipitate proteins. Enzymatic activities were stopped on ice for 5 min and terminated by acidifying with 90 µL of a 0.5% acetic acid solution. Then, aliquots were centrifuged at 10000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatants were collected and analyzed by RP-HPLC.

Assessment of AntinociceptionThe antinociceptive responses were assessed in Kunming mice using the warm water tail-flick test. Test groups (n = 6–8) were treated by intravenous (i.v.) injection (via tail vein) with EM-1, C18-CONH-EM1 NPs or C18-SS-EM1 NPs dispersed in water (10 µmol/kg). To present the locus of antinociception, animals were pretreated peripherally with opioid antagonists naloxone (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneal (i.p.)) and naloxone methiodide (50 mg/kg, i.p.) before i.v. challenge with peptide derivatives.

The warm water tail-flick test was performed as described earlier. The mouse tail was immersed in hot water maintained at 50 ± 0.2°C and the latencies to flicking, bending, and swing were measured. Before treatment, baseline latency times [control latency (CL)] were recorded and selected as 3–5 s; the maximum cut-off time was set at 10 s. The tail-flick responses were measured at designated times points after i.v. injection of drugs. The latency to tail-flick was defined as the test latency (TL) and 0.9% sodium chloride was used as control. The antinociceptive response was expressed by converting analgesic tail-flick times to percentage of maximal possible effect (%MPE): %MPE = 100 × (TL − CL)/(10 − CL).

NIR Fluorescence ImagingThe NIR fluorescent dye DiR was employed as a probe for fluorescent imaging by loading it onto C18-SS-EM1 NPs. An aliquot of 2 mg C18-SS-EM1 was dissolved in 1 mL of ethanol and 0.1 mL of a DiR solution (0.5 mg/mL) was added under stirring for 10 min at room temperature; this mixture was slowly added dropwise to deionized water and stirred moderately for 30 min. Then, the solution was dialyzed for 16 h to remove free dye molecules (molecular weight cutoff = 1000 g/mol). The dialysate was freeze-dried and dissolved in distilled water for the experiment in male BALB/c nude mice. In vivo imaging was performed using the IVIS Lumina II imaging system (Caliper Life Science). 15 µmol/L DiR-loaded C18-SS-EM1 NPs or DiR alone was injected into the tail vein of the mice (n = 3 for each group). Before optical imaging, the mice were anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane mixed with medical air using a gaseous anesthesia system. Whole body fluorescence images were recorded at 10, 30, 60, 90, 120, 240, and 360 min after the injection. Images were captured using a CCD camera and analyzed with the Lumina II Living Imaging 4 software. After completion of the in vivo fluorescence imaging studies, we performed the ex vivo NIR fluorescence imaging analysis. Animals were sacrificed within 1 h after i.v. administration and perfused with heparinized saline to remove the blood from the brain; the whole brains were removed and placed into the imaging system as described above.

Reduction Release Study of Self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 NPs in VitroThe in vitro release characteristics of the self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 NPs were evaluated in the presence or absence of dithiothreitol (DTT) by HPLC analysis. Briefly, 1 mmol/L self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 NPs was prepared in water. Equal volumes aqueous solutions of C18-SS-EM1 NPs and DTT were mixed to reach a final DTT concentration of 10 mmol/L. Then, the solutions were continuously mixed by horizontal shaking (100 rpm) at 37°C with or without DTT. At the designated time (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6 h), samples were collected and replaced with an equal volume of water. The intact prodrug content and release rate of C18-SS-EM1 NPs was determined by RP-HPLC.

Statistical AnalysisEach group were performed at least three independent experiments. All data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) except for the assessment of antinociception test using mean ± standard error (S.E.M.). Student’s t-test was used to compare the difference between two groups. p < 0.05 was considered to demonstrate a statistically significant difference (* p < 0.05).

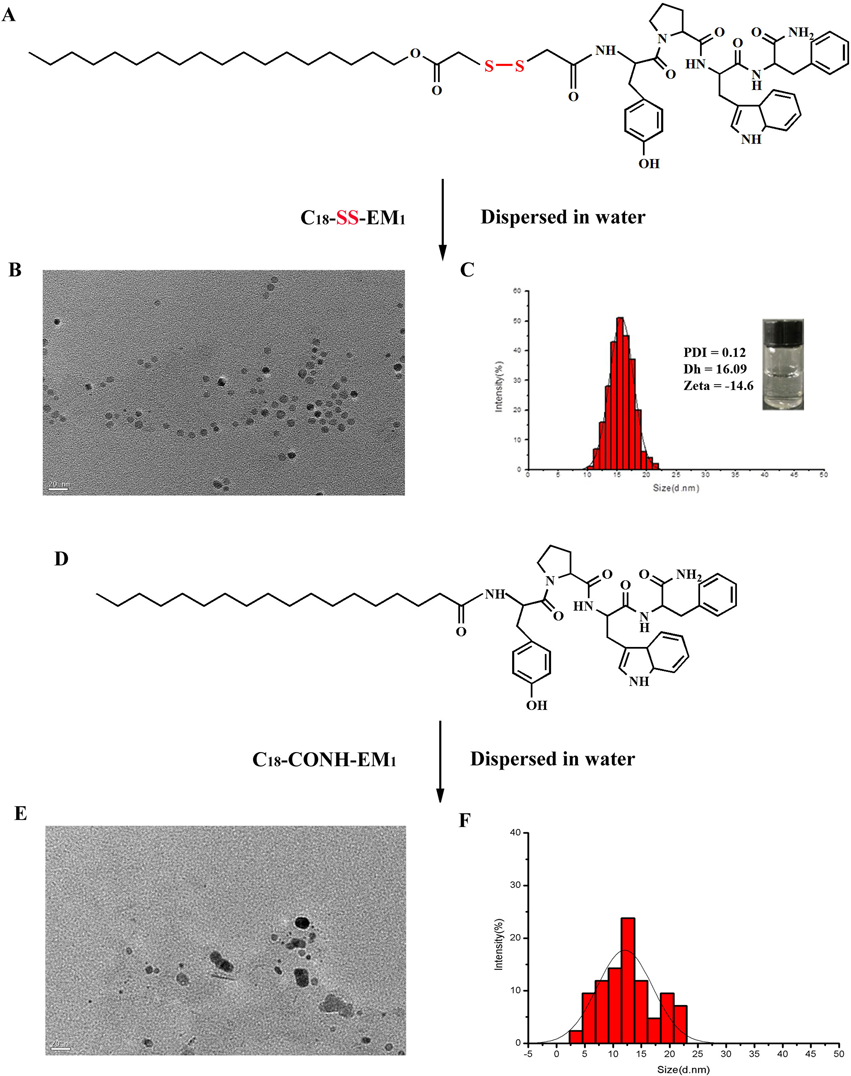

Two amphiphilic derivatives of EM-1, C18-CONH-EM1 and C18-SS-EM1, were synthesized using Fmoc-based chemistry, in which synthesis of the peptide was followed by the linking a stearic moiety to the tyrosine via an amide or disulfide bond as shown in Figs. 1A and D.

(A, D) Molecular structures of C18-SS-EM1 and C18-CONH-EM1. (B, E) TEM images of self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 and C18-CONH-EM1 NPs after dispersion in water. Scale bar: 20 nm. (C, F) DLS curve of C18-SS-EM1 and C18-CONH-EM1 NPs. Inset in Fig. C: a photograph of C18-SS-EM1 solution of nanomolecular. (The concentration was 10 µmol/L.) (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

The self-assembled nanoparticles were prepared according to the nanoprecipitation method. Figures 1B and E show TEM images of C18-SS-EM1 and C18-CONH-EM1 NPs, respectively. The C18-SS-EM1 can self-assemble into well-dispersed spherical nanostructures with uniform size (close to 15 nm), whereas the C18-CONH-EM1 generated non-uniform nanostructures under the same conditions (Fig. 1E). The consistent results were presented in the DLS curve. Compared with the self-assembled C18-CONH-EM1 NPs (Fig. 1F), the DLS curve of self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 NPs in aqueous solution indicated a narrow particle size distribution range of 10–20 nm with an average diameter of approximately 16.09 nm (Fig. 1C). The PDI value was 0.12, further confirming a narrow particle diameter distribution. The zeta potential, also determined by DLS, was negative (−14.6 mV). The inset in Fig. 1C showed a photograph of self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 NP in aqueous solution at a concentration of 10 µmol/L, maintaining a stable and transparent solution.

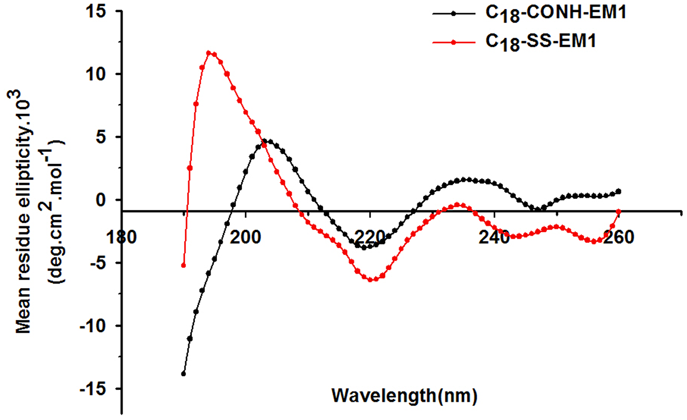

CD MeasurementsCD studies were conducted using the peptide derivatives at a 50 µmol/L concentration to investigate changes in the secondary structure. As shown in Fig. 2, the two amphiphilic EM-1 derivatives were associated with slightly different CD spectral features but shared the same trends. For C18-CONH-EM1, the most prominent features were an intense maximum at 205 nm and a minimum at 220 nm. While C18-SS-EM1 exhibited a similar minimum at 220 nm, it had a much stronger maximum at 195 nm and the molar ellipticity increased significantly. According to the α-helix and β-strand content prediction using the k2d3 software, the percentages β-strand in C18-CONH-EM1 and C18-SS-EM1 were 17.07 and 43.97, respectively. Thus, the CD analysis showed that the C18-SS-EM1 had a strong tendency to form β-strands.

(Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

Figure 3 illustrates the metabolic stability of EM-1 and the two self-assembled EM-1 derivative NPs. Whether in the serum or the brain homogenate, unmodified EM-1 was rapidly degraded within minutes, which corroborated previous results.25) The self-assembled C18-CONH-EM1 NPs displayed an almost equipotent metabolic stability, maintaining the original peptide level for up to 120 min in the serum as well as in the brain homogenate. For the self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 NPs, the degradation rate in serum was slightly lower than that of C18-CONH-EM1. In contrast, the cumulative degradation curve in the brain homogenate indicated a significant decrease of C18-SS-EM1 NPs over time with approximately 50% peptide remaining after 120 min, which may be caused by the cleavage of the disulfide bond.

Data are given as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

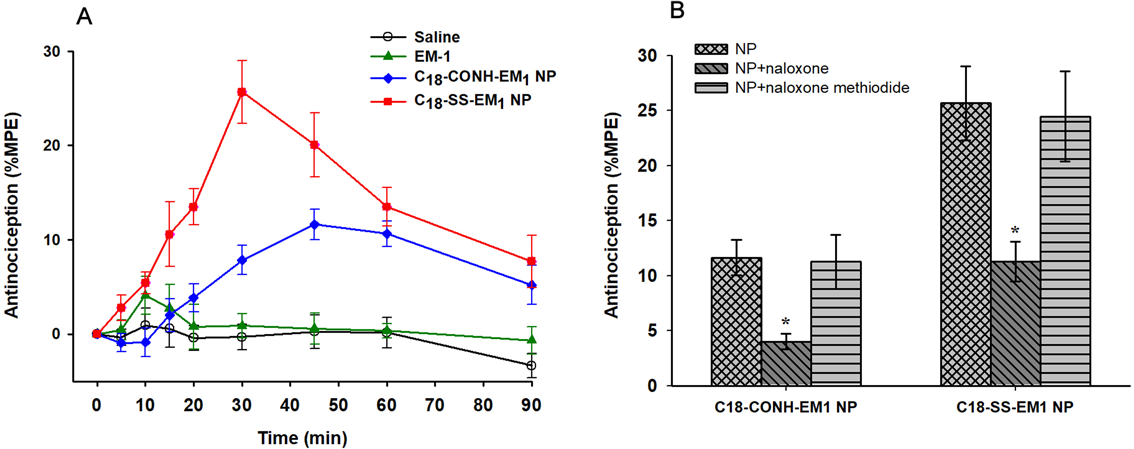

The analgesic effects of unmodified EM-1 or self-assembled EM-1 derivatives were assessed performing the tail-flick test on Kunming mice after i.v. administration. The results presented in Fig. 4A show that the i.v. injection of either C18-CONH-EM1 or C18-SS-EM1 NPs at a dose of 10 µmol/kg led to an enhanced analgesic activity. Especially the C18-SS-EM1 NPs displayed a strong analgesic activity, approximately 6.2-times more antinociception than unmodified EM-1 and 2-times more than C18-CONH-EM1 NP. The maximum analgesic effect of C18-SS-EM1 NPs was observed at 30 min after injection and longer durations of action were recorded up to 90 min. Furthermore, the mice were then pretreated with naloxone and naloxone methiodide to test whether the opioid antagonists were able to suppress the antinociceptive activity. Naloxone and naloxone methiodide both act on opioid receptors but naloxone methiodide has limited access to the brain. As shown in Fig. 4B, the antinociceptive effects of the EM-1 derivatives were effectively blocked by naloxone, suggesting that MOR was involved in producing analgesia. In contrast, naloxone methiodide did not alter the analgesic effect of i.v. administrated EM-1 derivatives, suggesting the site of action is only in the central.

Data are given as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 6–8). (B) Antagonism of antinociception elicited by 10 µmol/kg C18-CONH-EM1 and C18-CONH-EM1 NPs in the tail-flick assay by naloxone (50 mg/kg, i.p., administered 10 min before drugs) and by naloxone methiodide (50 mg/kg, i.p., administered 10 min before drugs). The error bar indicates the S.E.M. of the mean (n = 6–8), and the asterisk indicates that the response is significantly different from NP group (p < 0.05). (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

To demonstrate the delivery of self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 NPs into the mouse brain, fluorescence imaging experiments based on monitoring the fluorescence intensity of DiR were performed. Real-time in vivo images of the distribution of free DiR or DiR-labeled C18-SS-EM1 NPs in a living mouse are shown in Fig. 5A. Visible fluorescence accumulation of DiR-labeled C18-SS-EM1 NPs happened rapidly in the brain at 10 min after injection and reached the highest levels at 60 min. In contrast, the fluorescence signal from free DiR was eliminated quickly from the body and it only remained at very low levels in the brain.

(A) Optical in vivo imaging of nude mouse after i.v. administrated DiR-load C18-SS-EM1 NPs and free DiR. (B) Time course of fluorescence intensity (p/s/cm2/sr) after i.v. injection. (n = 3) (C) Ex vivo imaging of perfused mouse brains 30 min after i.v. injection of the DiR-load C18-SS-EM1 NPs and free DiR and saline as controls. (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

To confirm that the observed fluorescence signal was truly from the brain parenchyma and not from the vascular system, an ex vivo fluorescence imaging experiment was performed after whole-body optical imaging at 1 h. As shown in Fig. 5C, the strongest signal was observed in the brain of mice treated with C18-SS-EM1 NPs. Conversely, no significant fluorescence signal was detected in the brains of saline-treated mice and only a relatively weak signal was detected in the brains of DiR-treated mice.

Reduction Release Study of Self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 NPs in VitroThe release of the active peptide represents a critical step for self-assembled prodrugs to exert their function. Therefore, the reduction-responsive release behavior of C18-SS-EM1 NPs was tested in vitro in the presence or absence of DTT at 37°C. As shown in Fig. 6, the C18-SS-EM1 NPs treated with 10 mM DTT showed faster release rates than those without DTT. For example, after 2 h of incubation, the release of C18-SS-EM1 NPs in the presence of 10 mM DTT was 70%, whereas only 10% was released from the C18-SS-EM1 NPs without a reducing agent. The above result indicated that the in vitro release behavior of C18-SS-EM1 NPs was reduction-responsive.

Solutions were incubated in the presence or absence of 10 mM DTT. Data are given as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

Self-assembling peptide-based nanostructures and materials, such as cell-penetrating peptides,29,30) peptide amphiphiles21,31) or hydrogels,32) have been tested as delivery vectors for therapeutic molecules due to their inherent biocompatibility and biodegradable properties.

In this study, the pharmacologically active neuropeptide EM-1 was employed not only as cargo but also as an integral component of the drug delivery carrier. We synthesized two peptide derivatives composed of a stearyl moiety linked to the EM-1 by a disulfide bond (C18-SS-EM1) or an amide bond (C18-CONH-EM1). Based on the intrinsic amphiphilicity of the EM-1 derivatives, we predicted their self-assembly into nanovesicles in water. TEM was used to detect the potential nanostructures of self-assembled derivatives. We found that both EM-1 derivatives could self-assemble into a nanostructure, but the self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 had a more uniform morphology than the C18-CONH-EM1 and formed a homogeneous and monodisperse population according to the PDI value (Fig. 1C, insets). As shown in Fig. 1A, the chemical structure of the C18-SS-EM1 contains three essential elements: the stearic moiety, the active peptide EM-1, and the disulfide bond. First, the stearic moiety as the hydrophobic segment induces hydrophobic interactions, which are responsible for driving self-assembly and exposing the functional peptide group on the surface of the nanostructure.19) Second, the EM-1 (YPWF) is the active drug that serves as the hydrophilic segment of the amphiphilic derivative. This design dramatically increases the drug-loading capacity and diminishes potential side effects due to excipients. Third, a disulfide bond was chosen as a biodegradable linker to covalently attach the stearic moiety to the peptide. The disulfide bond can be rapidly cleaved in the presence of reducing agents such as GSH and has been extensively used as a reduction-responsive linker.27,33,34) Here, the only structural difference between the C18-SS-EM1 and C18-CONH-EM1 is the internal chemical bond, but their nanomorphology differed significantly. We hypothesize that the disulfide bond plays a wider role in the self-assembly. In general, disulfide bond formation is associated with protein folding and the S – S bonds show a preference for dihedral angles approaching 90°.27) This may play an essential role in balancing the intermolecular forces in peptide amphiphiles to control the self-assembly. Self-assembled C18-CONH-EM1 exhibited a poor nanomorphology possibly because of its strongly polar amide group. The CD spectra further supported a role of the disulfide bonds during the self-assembly process. The disulfide conjugate C18-SS-EM1 exhibited much stronger change at 195 nm (Fig. 2) and its β-strand content was approximately 2.5-fold higher than that of the amide conjugate C18-CONH-EM1, which demonstrated that the disulfide bond dramatically affected the CD spectra.

To study the resistance of the amphiphilic derivatives to enzymatic hydrolysis, fresh serum and 15% brain homogenate were chosen to simulate the conditions of the peripheral blood circulation and CNS environment. Like other small peptides, the EMs exhibited very poor metabolic stability and low membrane permeability. Lipidation has been shown as the most robust and effective approach to improve the metabolic stability of a peptide and its BBB transport.35,36) In this study, the stearyl moiety was introduced as the lipidic group, which improved the metabolic stability profile (Fig. 3). Having the same lipidation, the C18-CONH-EM1 displayed a similar degradation rate in the serum and in the brain homogenate, whereas the self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 NPs displayed a significantly faster degradation in the brain as shown in Fig. 3B. A possible interpretation is that C18-SS-EM1 was stable in the peripheral plasma until crossing the BBB but was subsequently cleaved in the reductive environment of the brain tissue to release its biologically active form from the self-assembled NPs. These results were further verified by the reduction-release in vitro study of self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 NPs (Fig. 6). After the addition of the reducing agent DTT, the C18-SS-EM1 NPs displayed a faster release rate than those without DTT.

The potent antinociceptive effect after peripheral administration indicates the ability of the peptide derivatives to cross the BBB. Compared with the free EM-1, the two self-assembled EM-1 derivatives with an internal amide or disulfide linkage produced an enhanced antinociceptive effect (Fig. 4A). That was probably related to the fatty acid modification. As described earlier, the lipidation as a modification increases the uptake by the brain by modulating peptide lipophilicity, which promotes translocation across the BBB by passive diffusion. Interestingly, although the stearic acid was incorporated into both peptide derivatives, the disulfide conjugate C18-SS-EM1 NPs exhibited approximately 2-fold stronger antinociception as compared to that of the amide-containing derivative C18-CONH-EM1. This is linked to the formation of self-assembled nanostructures of C18-SS-EM1. It is clear that the self-assembled nanoparticle arrangement prevents the access of peptidases to the EM-1 and protects the integrity of the peptide in the plasma. In addition, as shown in Fig. 4B, the antinociceptive effects after i.v. administration of the self-assembled EM1 derivative NPs were significantly reversed by naloxone but not by naloxone methiodide. Naloxone is known to potentially antagonize the antinociceptive effect induced by μ-opioid agonists on central and peripheral receptors. Naloxone methiodide, its quaternary derivative, is thought act only in the periphery and is used to distinguish between central and peripheral sites of action for drugs acting on opioid receptor. These results further revealed that the observed analgesic effects may involve central μ-opioid receptors.

To directly demonstrate that the peptide NPs crossed the BBB, the NIR dye DiR was employed as a fluorescent marker to monitor the distribution of C18-SS-EM1 NP in the brain. The in vivo and ex vivo studies showed that the fluorescence intensity of DiR-labeled C18-SS-EM1 NPs was significantly higher than that of the free DiR, indicating that the brain targeting of C18-SS-EM1 NPs was successful, confirming the results of the pharmacodynamics analysis.

As opioid-based pain treatment occurs mainly within the CNS, the opioid peptides including endomorphins should be able to cross the BBB intact.37,38) Van Dorpe et al. described the transport properties of EMs.39) Both EM-1 and EM-2 display high influx constant rates (Kin = 1.06 and 1.14 µL/(g × min), respectively), which were consistent with their log p values (2.04 and 1.94, respectively). Additionally, the capillary depletion method showed that EMs entered the brain parenchyma for about 90%. It is hence possible that the EMs penetrate the BBB by passive transmembrane diffusion. However, there are two factors influencing EM brain delivery. One factor is the presence of the efflux system at the BBB. In some studies Van Dorpe et al.39) and Kastin et al.,40,41) it is demonstrated that EM-1 and EM-2 entering the brain could be pumped out again by a saturable efflux system. The half-time disappearance is 15 and 22 min, respectively. Another factor is their fast degradation by peptidases. The study showed both EM-1 and EM-2 showed the poorest brain and plasma stability among the eight investigated opioid peptides. Compared to the brain tissue, the plasma showed half-life stabilities of a few minutes only. In present study, the prodrug strategy and nanocarriers were combined to enhance penetration of EM-1 across the BBB after systemic administration. The introduction of fatty acid is able to increase the lipophilic character of EM-1. The self-assembled nanoparticles can effectively avoid the enzymatic hydrolysis and readily cross BBB by small size mediated endocytotic mechanisms.

In this study, we successfully synthesized the reduction-responsive EM-1 derivative C18-SS-EM1. In an aqueous medium, it self-assembled into NPs. We concluded from our profiling experiments that the self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 NPs consisted of a hydrophobic core that was surface-decorated with peptide β-sheets. Based on the structural similarity to micelles, we concluded that the tightly arranged peptide moieties provide protection against peptide-degrading activities in the plasma and at the BBB. As compared with the unmodified EM-1 or the amide-linked C18-CONH-EM1, the self-assembled C18-SS-EM1 NPs exhibited significantly increased antinociceptive activities. The NIR fluorescent experiments further confirmed our hypothesis that the C18-SS-EM1 NPs could cross the BBB and accumulate in the mouse brain. In summary, the C18-SS-EM1 NP design integrated the advantages of lipidization, nanocarriers and, a labile disulfide bond that resulted in improved brain targeting, which indicated the great potential of the self-assembled prodrug NPs in brain drug delivery and therapy.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81773564); the Key Science and Technology Program of the Gansu Province (No. 17YF1FA125); the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province (No. 17JR5RA204); and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. lzujbky-2016-144, lzujbky-2017-204).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.