Case Description

A 46-year-old man presented with headache, rapid weight loss (10 kg/year), hyperhidrosis, tachycardia (110 bpm), severe hypertension (220/130 mmHg) and hyperglycemia (fasting plasma glucose 350 mg/dL, glycated albumin 23.6%, HbA1c 8.3%). There were not typical Cushingoid appearances, such as moon face, buffalo hump or central obesity. There was not apparent hyperpigmentation. There was no family history of pheochromocytoma or correlates except for stroke in his maternal grandparents. Height was 170 cm and body weight was 52 kg (body mass index of 18.0 kg/m2). Initial examination revealed hypokalemia (3.0 mEq/L), severe dehydration without diabetic ketoacidosis, and liver dysfunction (Tables 1, 2). He was referred to our hospital for further investigation and treatment.

Table 1

Clinical data of the present case and reported cases with metyrapone-sensitive ectopic ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma

| Author |

Present case |

White et al. [16] |

Sakuma et al. [33] |

| Year |

2017 |

2000 |

2016 |

| Sex |

Male |

Female |

Female |

| Age |

46 |

44 |

56 |

| Clinical manifestation |

|

|

|

| Cushingoid appearance |

(–) |

(+) |

(+) |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 |

18.0 |

|

32.8 |

| Blood Pressure, mmHg |

220/130 |

220/130 |

153/93 |

| Fasting blood glucose, mg/dL |

350 ↑ |

NA |

341 ↑ |

| Serum potassium, mEq/L |

3.0 |

2.3 |

NA |

| Liver dysfunction |

(+) |

(+) |

NA |

| Results of dexamethasone suppression test |

|

|

|

| ACTH, pg/mL |

before |

270.5 |

NA |

18.4a |

|

0.5 mg |

331.9 |

|

NA |

|

1 mg |

237.6 |

|

18.4a |

|

8 mg |

390 |

|

241a |

| Cortisol, μg/dL |

before |

32.3 |

|

<1.0a |

|

0.5 mg |

41.2 |

|

NA |

|

1 mg |

25.8 |

|

<1.0a |

|

8 mg |

34.8 |

|

<1.0a |

| Pheochromocytoma |

|

|

|

| Site/Size, cm |

Right/6.0 |

Left/4.0 |

Left/5.3 |

| MIBG scintigraphy |

(–) |

(+) |

(+) |

| Hyperplasia of cortex |

not apparent |

contralateral |

bilateral |

ACTH, adrenocorticotrophin; NA, Not available

a Dexamethasone suppression test was performed taking 6 g/day of metyrapone.

Table 2

Clinical data—before (B) and after (A) metyrapone treatment and post operation (Postop)—of the present case compared with reported cases with metyrapone-sensitive ectopic ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma

| Author |

Present case |

|

(Postop) |

White et al. [16] |

Sakuma et al. [33] |

| Dose of metyrapone (g/day) |

0.5→0.25 |

|

none |

1.0a |

4.0→6.0 |

| Serum or plasma |

|

|

A/B (%) |

|

|

|

| Cortisol, μg/dL |

B |

32.3 |

|

1.7 |

>60.2 |

85.6 |

| (4.0–18.3) |

A |

5.5 |

(17.0%) |

|

2.6 |

<1.0 |

| ACTH, pg/mL |

B |

270.5 |

|

5.4 |

927 |

995 |

| (7.2–63.3) |

A |

34.8 |

(12.8%) |

|

50.0 |

18.4 |

| Adrenaline, pg/mL |

B |

4,448 |

|

5 |

NA |

589 |

| (<100) |

A |

1,139 |

(25.6%) |

|

|

NA |

| Noradrenaline, pg/mL |

B |

8,901 |

|

228 |

NA |

1,342 |

| (100–450) |

A |

3,965 |

(44.5%) |

|

|

NA |

| Dopamine, pg/mL |

B |

203 |

|

14 |

NA |

68 |

| (<20) |

A |

21 |

(10.3%) |

|

|

NA |

| ACTH/Cortisol ratiob |

B |

8.4 × 10–4 |

|

3.2 × 10–4 |

<15.4 × 10–4 |

11.6 × 10–4 |

| (1–4 × 10–4) |

A |

6.3 × 10–4 |

|

|

19.4 × 10–4 |

>18.4 × 10–4 |

| Adrenaline/Cortisol ratioc |

B |

137.7 × 10–4 |

|

|

NA |

6.9 × 10–4 |

| (<25 × 10–4) |

A |

207.1 × 10–4 |

|

|

|

|

| POMC, pmol/L |

B |

NA |

|

|

1,625 |

NA |

|

A |

NA |

|

|

163 |

NA |

| ALT/AST, U/L |

B |

119/38 |

|

|

NA |

NA |

|

A |

15/12 |

|

15/13 |

|

|

| Blood Pressure, mmHg |

B |

220/130 |

|

|

200/130 |

153/93 |

|

A |

128/80 |

|

124/78 |

110/70 |

|

| Urine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Free cortisol, μg/day |

B |

765 |

|

NA |

NA |

1,250 |

| (26–187) |

A |

15.1 |

(2.0%) |

|

|

NA |

| Adrenaline, μg/day |

B |

2,590 |

|

NA |

1,181 |

244.4 |

| (3–30) |

A |

239.4 |

(9.2%) |

|

NA |

NA |

| Noradrenaline, μg/day |

B |

3,130 |

|

NA |

1,444 |

1,175.8 |

| (30–150) |

A |

619.9 |

(19.8%) |

|

NA |

NA |

| Dopamine, μg/day |

B |

1,536 |

|

NA |

NA |

669.8 |

| (350–950) |

A |

188.2 |

(12.3%) |

|

|

NA |

| Metanephrine, μg/day |

B |

6,660 |

|

10 |

NA |

1,120 |

| (40–190) |

A |

1,110 |

(16.7%) |

|

|

440 |

| Normetanephrine, μg/day |

B |

2,590 |

|

40 |

NA |

1,290 |

| (90–330) |

A |

990 |

(38.2%) |

|

|

540 |

ACTH, adrenocorticotrophin; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; NA, Not available; ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AST, Aspartate aminotransferase; Numbers in parenthesis are reference values.

a 0.75 mg dexamethasone was added for replacement

b Calculated as plasma ACTH divided by serum cortisol

c Calculated as plasma adrenaline divided by serum cortisol

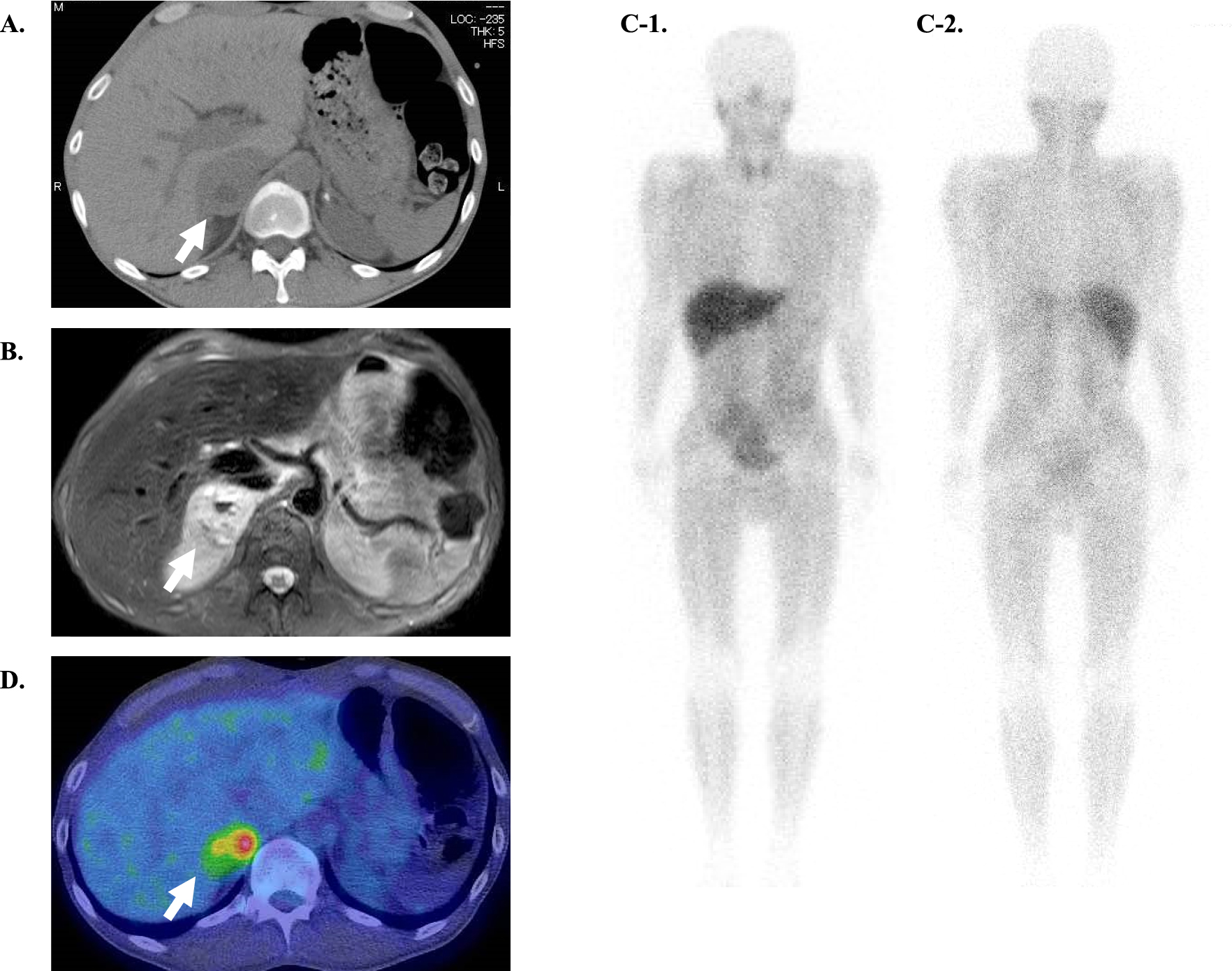

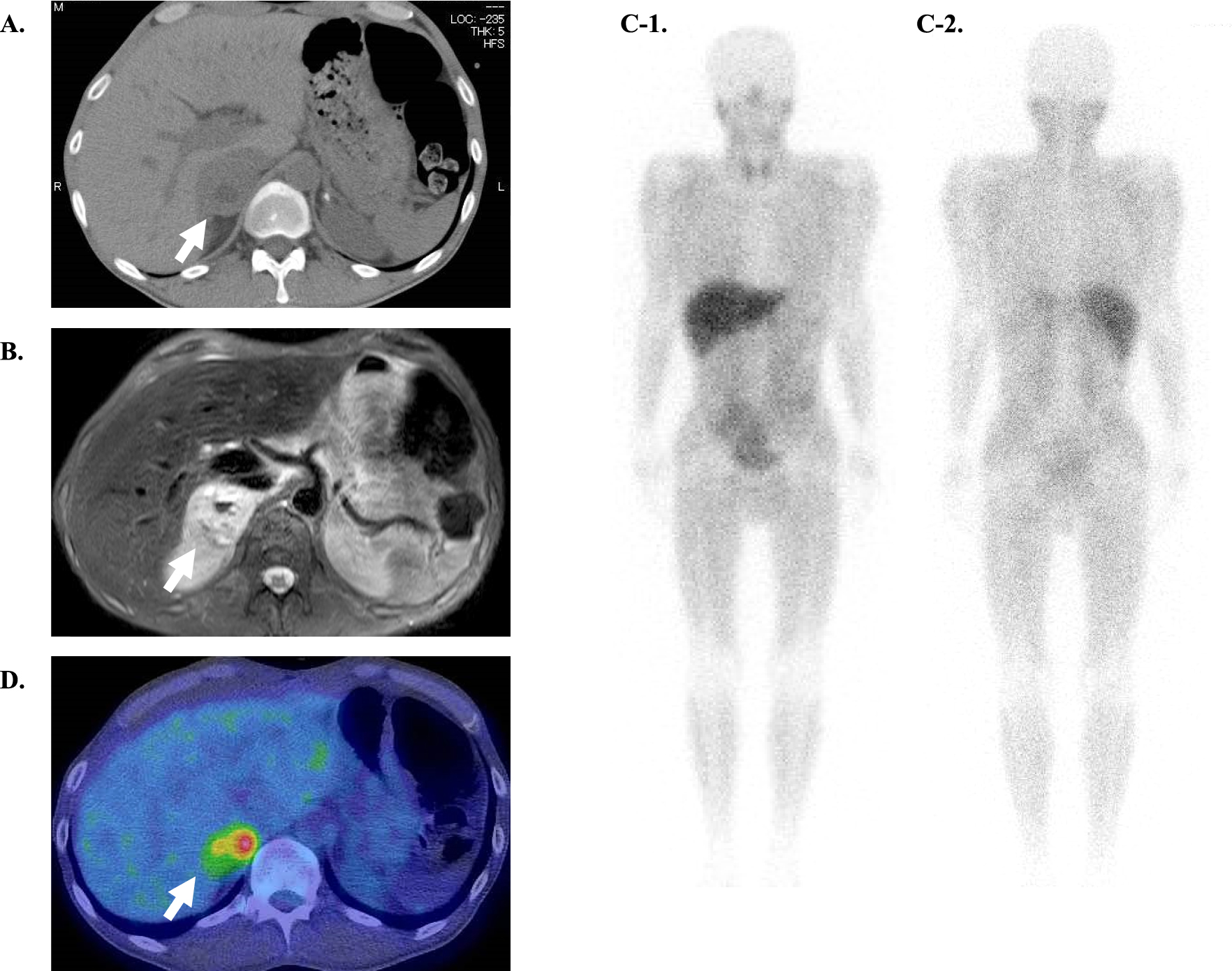

Laboratory studies displayed extremely high levels of plasma and urine catecholamines and their metabolites (Table 2). Plain CT revealed a 6.0 cm right adrenal tumor with high- and low-density area, suggesting intratumoral hemorrhage and necrosis respectively (Fig. 1A). Plain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed mainly a T1-low and T2-high tumor, with mixed-intensity area suggesting intratumoral hemorrhage and necrosis (Fig. 1B). 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy showed no accumulation in the tumor (Fig. 1C), while 18F-FDG positron emission tomography (PET) showed uptake in the area of the adrenal tumor, mainly the marginal area (SUVmax 6.25) (Fig. 1D). Laboratory studies also displayed an elevated plasma ACTH level (270.5 pg/mL) and serum cortisol level (32.3 μg/dL at 9:00 a.m.) with an extremely high ACTH/cortisol ratio (8.4 × 10–4), suggesting ACTH-driven hypercortisolemia (Table 2). Serum cortisol remained elevated after overnight 0.5-mg, 1-mg, and 8-mg dexamethasone suppression. Intriguingly, dexamethasone paradoxically stimulated ACTH secretion (Table 1). Furthermore, 24-h urinary-free cortisol was very high (765 μg/24 h). Several imaging studied (Plain CT, MRI, Enhanced pituitary MRI and 18F-FDG PET) were performed to rule out pituitary abnormality or any other ectopic source of ACTH. With these investigations suggesting elevated catecholamine levels accompanied with ACTH-driven hypercortisolemia, the right adrenal tumor was diagnosed to be an ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma. The characteristic of this patient was his extremely elevated levels of catecholamine (Table 2).

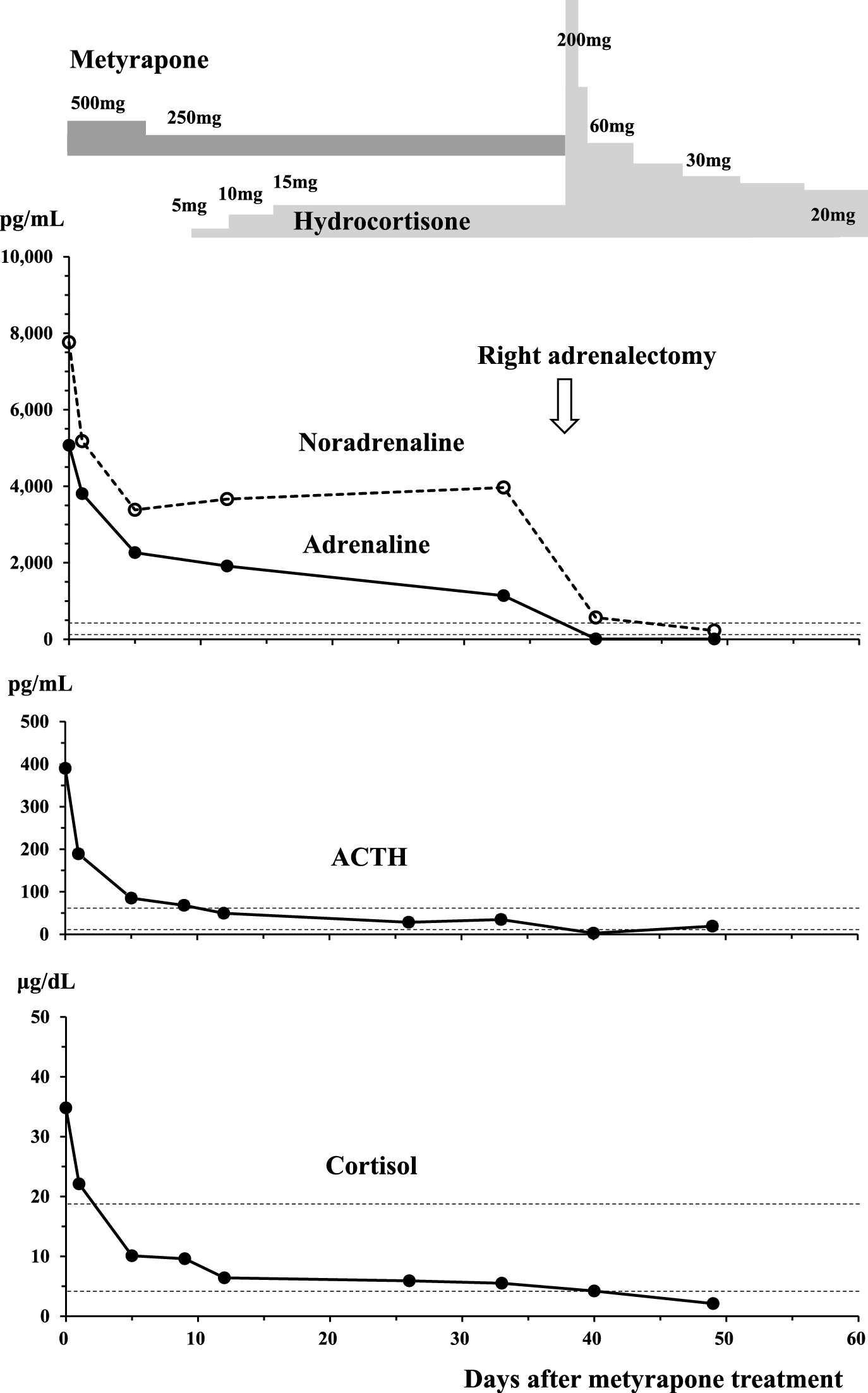

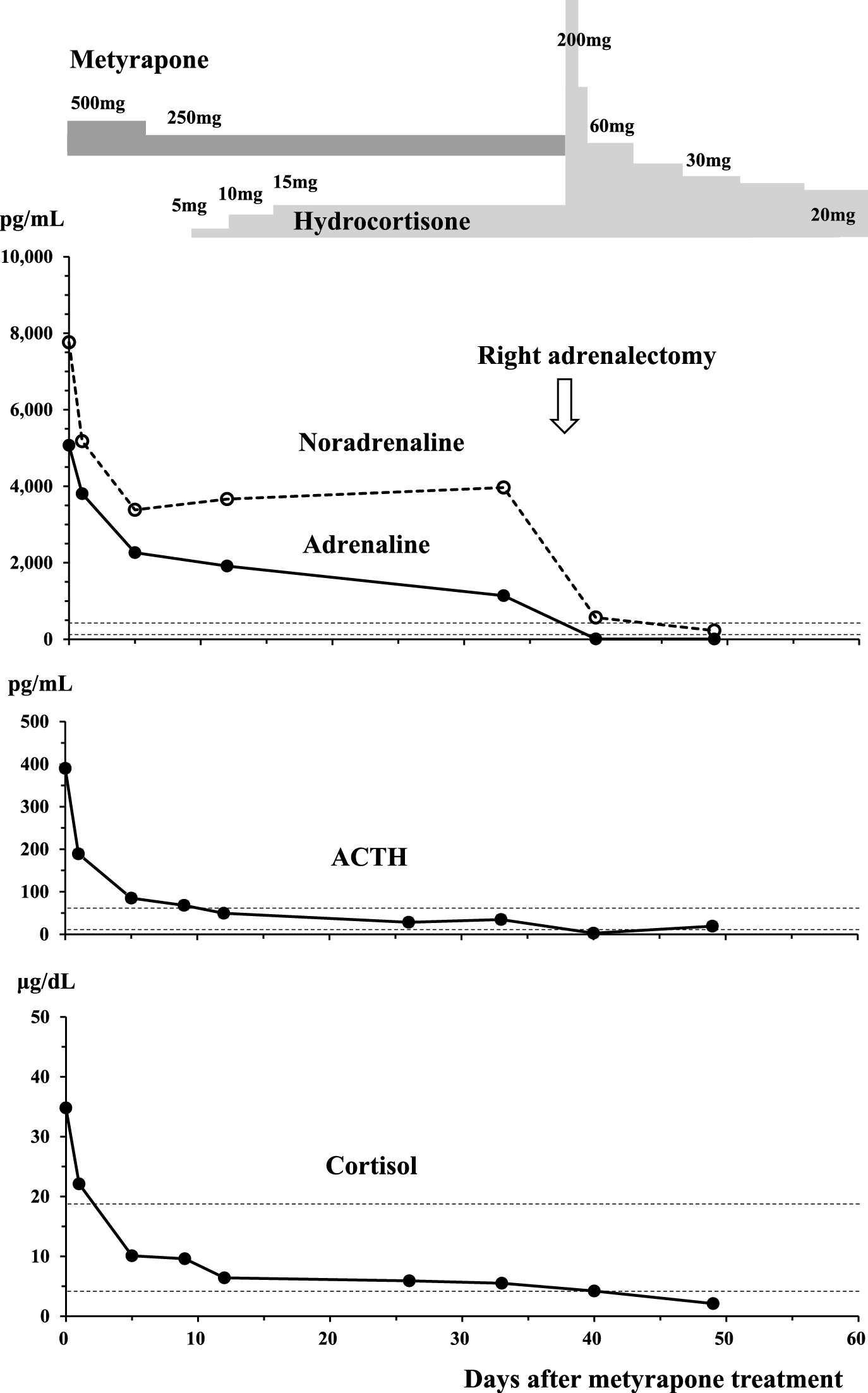

A right adrenalectomy was planned, and he was initiated on α- and β-adrenoceptor blockade treatment (doxazosin titrated up to 16 mg/day, followed by carvedilol 10 mg/day) with continuous saline infusion of 2,000 mL/day. After medication and hydration to some extent (15 days after admission), the hypercortisolemia was treated with the 11-β-hydroxylase inhibitor metyrapone 500 mg/day (Fig. 2). After two days, he lost 2 kg of body weight and complained of severe thirst suggesting dehydration, requiring physiological saline infusion of 3,000 mL/day. His serum cortisol level rapidly and exponentially dropped to 6.4 μg/dL. His dosage of metyrapone was reduced to 250 mg/day and hydrocortisone supplementation was initiated (titrated up to 15 mg/day). Intriguingly, after the introduction of metyrapone treatment, his plasma ACTH level was also rapidly and exponentially decreased from 390.0 pg/mL to 85.1 pg/mL after 6 days, and then to 34.8 pg/mL after 33 days (Fig. 2).

More remarkably, plasma and urine catecholamine levels were decreased along with the correction of the hypercortisolemia (Fig. 2, Table 2), although the levels remained higher than normal. Pre-operatively, his blood pressure and heart rate became stable (128/80 mmHg and 80 bpm by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM)), and his plasma glucose levels were gradually stabilized by intensive-insulin therapy (26 units/day). Hypokalemia was improved and serum liver transaminase became normal (Table 2).

Right laparoscopic adrenalectomy, which was performed uneventfully 50 days after admission, resulted in complete remission of pheochromocytoma and Cushing’s syndrome. His blood pressure and heart rate dropped to within normal range without medication (124/78 mmHg and 80 bpm by ABPM). He presented normal glucose tolerance by a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (75 g OGTT) and no longer required potassium replacement. There were no signs of recurrence or metastasis one year after the surgical treatment. Plasma ACTH level became extremely low after adrenalectomy (Table 2, Fig. 2), requiring hydrocortisone replacement for about one year.

Discussion

The characteristics of this case were 1) abrupt onset of pheochromocytoma and Cushing’s syndrome without typical Cushingoid appearance, 2) extremely elevated plasma ACTH and catecholamine levels with high ACTH/cortisol ratio, 3) paradoxical elevation of both his plasma ACTH and serum cortisol level during the dexamethasone suppression test, 4) almost parallel exponential decrease not only in serum cortisol but also in plasma ACTH and catecholamine levels during metyrapone treatment, and 5) 123I-MIBG scintigraphy-negative pheochromocytoma. Most of these characteristics were well explained by the confirmation of a catecholamine-dominant ectopic ACTH secreting pheochromocytoma with the recently clarified glucocorticoid-driven positive-feedback regulation [33], resulting in a vicious cycle of cortisol and catecholamine overproduction.

Our case satisfied all the diagnostic criteria of ectopic ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma proposed by Chen H et al. [12], including 1) hypercortisolemia, 2) elevated plasma ACTH levels, 3) biochemical evidence of a pheochromocytoma and MRI evidence of an adrenal mass with a bright T2 signal, 4) resolution of symptoms and signs of adrenocorticoid and catecholamine excess after unilateral adrenalectomy, and 5) rapid normalization of plasma ACTH levels after adrenalectomy. However, the criteria 5) should be changed to rapid normalization or suppression of plasma ACTH levels after adrenalectomy using more sensitive ACTH assay. Furthermore, diagnosis of ectopic ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma was histologically and biochemically confirmed by positive staining with synaptphysin, chromogranin A, and ACTH.

Among various types of Cushing’s syndrome, the absence of a negative-feedback mechanism may be observed in corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)-secreting tumor or ectopic ACTH-secreting syndrome. More interestingly, positive feedback has been suggested by increased proopiomelanocortin (POMC) production by dexamethasone [16, 33] or increased CRH production by dexamethasone in a human pheochromocytoma cell line [40].

Considering whether this positive-feedback phenomenon was the characteristic of an ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma, 69 cases from 47 reports of ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma reported in the English literature since 1977 and the present case were evaluated [2-35]. The mean age of patients was 49 ± 14 years. Hypertension, hyperglycemia, Cushingoid appearance, hyperpigmentation, and hypokalemia were present in 94%, 90%, 88%, 10%, and 85% of cases, respectively. Tumors were 4.5 ± 2.0 cm in diameter on average, and 123I-MIBG scintigraphy revealed abnormal accumulation in the tumor in 53% of the cases. Severe hypertension and hyperglycemia, found in this case, are common in patients with ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma, suggesting an additive or synergistic effect of excess catecholamine and excess glucocorticoid. Cushingoid appearance was found in many of the cases, but was not found in 2 slim patients including the present case [6]. Acute clinical deterioration was described in many of the cases.

A dexamethasone suppression test was performed in 32 cases, with suppression not observed in most patients. Careful evaluation of the data suggested that paradoxical elevation of serum cortisol and/or ACTH level occurred in 9 cases including ours [3, 11, 19, 22, 23, 29, 33, 35]. However, evaluation of the positive-feedback phenomenon was difficult when serum cortisol or plasma ACTH levels had been already high before the test. The dose-dependent paradoxical response was more clearly shown when the suppression test was performed during metyrapone treatment, because the serum cortisol level before suppression was almost null [33].

Metyrapone is effective for short- and long-term control of hypercortisolemia in Cushing’s syndrome of all types [41-43]. After metyrapone administrations, plasma ACTH levels usually increase in patients with pituitary Cushing’s disease and ectopic ACTH syndrome [41, 42]. Clinical responses to metyrapone administration were reported in 7 cases of ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma [9, 11, 16, 17, 28, 33, 34]. Metyrapone treatment was not sufficiently effective in one case [28], and an increase in plasma ACTH level and a decrease in serum cortisol level were observed in another case [9]. However, a paradoxical decrease in plasma ACTH accompanying the decrease in serum cortisol was suggested in 5 patients. This phenomenon may be explained by the positive-feedback control of ACTH production by glucocorticoid. Since the decrease in the plasma ACTH level was small or ambiguous in two patients, the presence of a positive-feedback loop was tentatively diagnosed when the plasma ACTH level fell below 20% of the level before metyrapone treatment in this study, as shown in three patients including our own (Table 2).

While very high plasma ACTH levels may be seen in ectopic ACTH syndrome (>100 pg/mL), the values frequently overlap those seen in Cushing’s disease [44]. Theoretically, the plasma ACTH/serum cortisol ratio could be a useful marker for evaluating the negative-feedback system. The ACTH/cortisol ratio should be close to zero in Cushing’s syndrome induced by primary adrenocortical disease. The ACTH/cortisol ratios in reported cases with ectopic ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma are shown in Fig. 4, together with the values in pituitary Cushing’s disease calculated from the report of Nieman LK et al. [45]. There was no significant correlation between serum cortisol levels and the ACTH/cortisol ratio, that would suggest a negative-feedback phenomenon, especially in Cushing’s disease. On the other hand, it was interesting to find a positive correlation between plasma ACTH level and ACTH/cortisol ratio, not only in Cushing’s disease but also in ectopic ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma. It was also suggested that both the plasma ACTH level and ACTH/cortisol ratio were extremely high in three clinically proven cases with positive-feedback regulation [16, 33]. Fig. 4 suggests that when the plasma ACTH level is higher than 200 pg/mL or the ACTH/cortisol ratio is higher than 6 × 10–4, an ectopic ACTH-producing tumor with or without positive-feedback regulation should be kept in mind. In the present case, the serum cortisol level was slightly lower than in the other patients with ectopic ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma. The absence of apparent adrenocortical hyperplasia found at surgery might suggest that adrenocortical responsiveness to ectopically produced ACTH might have been reduced in our patient.

Sakuma et al. also showed a dose-dependent increase in serum catecholamine levels during the dexamethasone suppression test, in addition to the paradoxical increase in plasma ACTH level. They also suggested the decrease in urine metanephrine or normetanephrine excretion during metyrapone treatment. We also confirmed the dramatic decrease in plasma and urine catecholamine levels with the decrease in serum cortisol and plasma ACTH level by metyrapone (Table 2, Fig. 2). This was really a unique observation.

As to the correlation between adrenal cortex and medulla, it has been well known that glucocorticoids stimulate the synthesis of catecholamines through the induction of phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) [46, 47]. However, from the clinical point of view, it has been clearly shown that administration of glucocorticoid in healthy volunteers has very little effect on serum catecholamine levels [48]. It was then suggested that excess glucocorticoid may not have any serious effect on the adrenal medulla in healthy adults. Therefore, the decrease in the serum catecholamine level following the decrease in the serum cortisol level during metyrapone therapy confirmed in our patient was quite a distinctive phenomenon, although the inhibition of catecholamine synthesis by metyrosine, which inhibits TH, is well known [49].

On the other hand, pheochromocytoma crisis after the administration of glucocorticoid has been reported and reviewed in several papers [50, 51], leading to a fatal clinical course in 32% of the patients [50]. A pheochromocytoma crisis induced by the dexamethasone suppression test was also reported [52]. This might suggest glucocorticoid stimulation of catecholamine synthesis in the tumor. Several studies have suggested that steroids have permissive effects on the vasoactive response to catecholamines in peripheral tissues through receptors found on endothelial and smooth muscle cells [53], which could also be responsible for the steroid-induced pheochromocytoma crisis.

On the contrary, we must also pay attention to the possibility of hypoadrenalism during metyrapone treatment. High levels of cortisol found in ectopic ACTH syndrome may overwhelm the 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 enzyme in the kidney, allowing cortisol to act as a mineralocorticoid [54]. Therefore, approximately 70% of patients with ectopic ACTH syndrome have hypokalemia compared with only 10% in Cushing’s disease. Both catecholamine and glucocorticoid excess have complex effects on adipogenesis and lipolysis. The plasma (4,448 pg/mL) and urinary (2,590 μg/day) adrenaline levels in the present case were extremely high, compared to the reported levels of 589–2,870 pg/mL [8, 14, 22, 29, 33] and 5.8–302 μg/day [17, 19, 22, 23, 29, 30, 32, 33], respectively, in ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma. The extremely high levels of catecholamine suggested catecholamine-dominant ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma, explaining the patient’s weight loss, lack of typical Cushingoid appearances and low BMI, probably through enhanced lipolysis within the body. In these situations, the effect of metyrapone is striking. The decrease in cortisol is rapid, with trough levels at 2 hours post dose [41-43]. In the present case, dehydration was exacerbated two days after the initiation of the metyrapone treatment, probably through hypoadrenalism in the presence of sustained hypercatecholaminemia, resulting in enhanced lipolysis producing more metabolic water and loss of mineralocorticoid action including renal reabsorption of sodium and free water. Thus, the patient required corticosteroid replacement with metyrapone treatment. In the special conditions of pheochromocytoma, the protective and lifesaving effect of steroids was suggested for preventing epinephrine shock [55]. Thus, rapid improvement of hypercortisolemia in the presence of hypercatecholaminemia might be dangerous resulting in hypoadrenalism.

Therefore, we must be careful in performing the dexamethasone suppression test or metyrapone test, when an ectopic ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma is suspected. From the therapeutic point of view, metyrapone administration with dexamethasone supplementation [16, 33] may be the safest and most useful first therapeutic test before surgery.

Considering the life-saving effect of glucocorticoid in emergency, we further evaluated the problem whether catecholamine crisis can be quenched by intrinsic hypercortisolemia in ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma. Review of the literature suggested that the incidence of crisis was 10.3%, and short-term mortality was 33.3% before 1990 and 3.3% after 1990, which were not significantly different from those of usual cases of pheochromocytoma [56-60]. Causes of perioperative mortality included mostly vascular accident such as myocardial infarction [2], shock followed by sudden cardiac arrest [5] or sepsis [30]. Loh et al. reported hypertensive encephalopathy crisis during ketoconazole treatment [13]. The interaction of catecholamine excess and glucocorticoid excess seems to be complicated but very important. Both beneficial and deteriorating effects of chronic glucocorticoid excess were suggested. Further studies may be required to elucidate the interaction of catecholamine and glucocorticoid, not only in hemodynamics but also in lipid or water metabolism.

The glucocorticoid-driven positive feedback clearly explains the relatively rapid exacerbation of Cushing’s syndrome and pheochromocytoma through a vicious cycle, compared with adrenal or pituitary Cushing’s syndrome in which a negative-feedback system works as a brake. The mechanisms for this positive feedback may be related to the neoplastic character of ACTH-secreting tumors. It must be pointed out that in our case the plasma ACTH level became extremely low (Table 2, Fig. 2) after laparoscopic adrenalectomy. This suggests that the pituitary gland itself had been suppressed by glucocorticoid-driven negative-feedback regulation and that positive-feedback regulation might be specific to ectopic ACTH production.

In the normal pituitary, glucocorticoids inhibit POMC by binding to the glucocorticoid receptors which translocate to the nucleus and interact with the negative glucocorticoid response element of the POMC promoter [61]. In our case the pheochromocytoma was consisted of many synaptophysin- and chromogranin A-positive cells and sparsely distributed ACTH-positive cells. These cells appeared to be mutually exclusive. Sakuma et al. reported the same findings and that ACTH-positive cells contained primarily chromogranin A, suggesting a neuroendocrine tumor possibly arising from the same origin as the pheochromocytoma cells. Glucocorticoid receptors were detected in most cells. There may be some abnormality in glucocorticoid signaling in the POMC gene in ectopic ACTH-secreting neoplasms. Sakuma et al. suggested that hypomethylation of the POMC promoter of the tumor, particularly the E2F binding site, may be responsible for the paradoxical ACTH response to dexamethasone [33]. They also demonstrated the dose dependent stimulation of catecholamine synthesis by dexamethasone in vivo and in vitro, with upregulated POMC, TH and PNMT mRNA expression [33], as previously suggested in dexamethasone-treated rats in vivo [46].

As to the histological findings, immunohistochemistry for ACTH was carried out with anti-ACTH antibody from DAKO Cytomation (Glostrup, Denmark, 1:75 dilution) in our case, which is specific to the C-terminal portion of ACTH (amino acid 24–39). Despite the diagnosis of ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma, it may well be high-molecular-weight ACTH precursors or “big” ACTH that are responsible for Cushing’s syndrome with or without pigmentation, as reported by White et al. [16]. Cassarino et al. reported a case of ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma with negative immunostaining for ACTH [29]. Interestingly, expression of POMC mRNA in the ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma was markedly increased compared to that in cases of pheochromocytoma not associated with Cushing’s syndrome [29]. In the present case, ACTH-positive cells were distributed sparsely within the tumor, which could have been the insufficient recognition of high-molecular-weight ACTH precursors secreted from the tumor. Further studies are required to elucidate the unusual processing of POMC in ectopic ACTH-producing tumors.

Finally, we have described a relatively rare case of 123I-MIBG scintigraphy negative pheochromocytoma. The sensitivity of 123I-MIBG scintigraphy in pheochromocytoma is reported to be 94% [62]. In ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma, however, the tumors were confirmed to be 123I-MIBG scintigraphy negative in 8 cases [11, 12, 17, 22, 29]. It has been reported that a negative finding in the 123I-MIBG scintigraphy is frequently associated with malignant pheochromocytoma or SDHB mutations [63], and it is well established that pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas caused by SDHB mutations are associated with shorter survival and a higher incidence of malignancy [64, 65]. In the present case, expression of SDHB was preserved immunohistochemically, and there were no clinical implications for malignancy at the post-operative stage. The patient will need continuous careful monitoring following the surgery.