2015 Volume 21 Issue 5 Pages 639-647

2015 Volume 21 Issue 5 Pages 639-647

Acyl ascorbates were synthesized through the condensation of L-ascorbic acid with various fatty acids using an immobilized lipase in water-miscible organic solvent, and their antioxidative properties on lipid oxidation in bulk, disperse and microcapsule systems were examined. The optimal conditions for enzymatic synthesis in a batch reaction were determined and the continuous production of acyl ascorbate was conducted using a continuous stirred tank reactor and a plug flow reactor. The oxidative stability of lipid with saturated acyl ascorbate in bulk system increased with increasing acyl chain length, whereas that in the oil-in-water emulsion and microcapsule system depended on the acyl chain length and the concentration of the ascorbate.

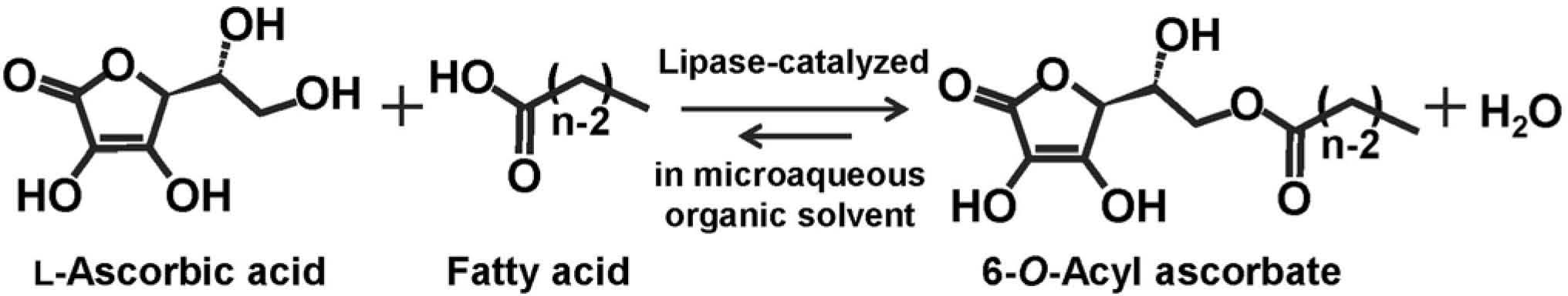

Lipid, which is one of the main components in food, is susceptible to oxidation, resulting in the generation of undesirable flavors and toxic products such as hydroperoxides. Therefore, lipid oxidation has received much attention due to its involvement in food deterioration and the relevance of lipid peroxidation in vivo to membrane damage, cancer, heart disease and aging (Cosgrove et al., 1987). Lipid oxidation is a complicated process consisting of three steps: initiation, propagation and termination, and the reaction mechanism has been elucidated in detail (Endo, 1998; Frankel, 1991; Porter, 1986). The addition of an antioxidant is one way to suppress oxidation, as the antioxidant may lengthen the oxidation induction period at very low concentrations (Gwo et al., 1985). These are usually phenolic compounds such as tocopherols, butylated hydroxyanisole, butylated hydroxytoluene and propyl gallate, and are used to inhibit the chain reaction by scavenging free radicals generated from lipid molecules. l-Ascorbic acid is a water-soluble compound also known as vitamin C. It is used widely as an additive in foods and cosmetics owing to its strong reducing ability. Its lipophilic derivatives are acylated with a long-chain fatty acid, such as palmitic acid, and used in lipid-rich foods (Enomoto et al., 1991). These are mainly synthesized by a chemical procedure (Tanaka and Yamamoto, 1966), and are edible surfactants because each substrate is eaten daily. The antitumor activity and metastasis-inhibitory effects of 6-O-palmitoyl ascorbate have been reported (Miwa and Yamazaki, 1986; Nagao et al., 1996). In addition, the 6-O- and 2-O-monoesters of ascorbic acid with phosphate or fatty acid are known to have physiological activity equivalent to unmodified ascorbic acid (Inagaki and Kawaguchi, 1966). Acyl ascorbate consists of an ascorbyl moiety as the hydrophilic group and an acyl residue as the hydrophobic group, and therefore is a promising emulsifier with both reductivity and surface activity. However, palmitoyl and stearoyl ascorbates, which are commercially available, are highly water insoluble, preventing their use as an emulsifier in oil-in-water emulsions. Ascorbates with short acyl chains would be more water-soluble and have greater potential for use in preparing emulsions than those with long acyl chains. Medium-chain fatty acids or their esters with glycerol have been recognized to improve the absorption of hydrophilic substances in the intestine (Shima et al., 1997). Thus, it is expected that an ester of ascorbic acid with medium-chain fatty acid itself could be easily absorbed in the intestine with the physiological activity of vitamin C or that the ester could facilitate the absorption of hydrophilic substances. Fatty acids are classified as saturated or unsaturated fatty acids. Polyunsaturated fatty acids are not synthesized in the human body (Miyazaki et al., 2001) and have important physiological functions such as a cholesterol-lowering agent, and antithrombotic and antiallergenic properties (Linko and Hayakawa, 1996; Yoshii et al., 1999). However, polyunsaturated fatty acids are extremely susceptible to oxidation compared to monounsaturated and saturated fatty acids (Song et al., 1997). Acyl ascorbates with a long acyl chain length would effectively oxidize polyunsaturated lipids due to their lipophilic property. Furthermore, the esterification of polyunsaturated fatty acid with ascorbic acid is expected to improve the oxidative stability of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Enzymatic synthesis of acyl ascorbate would be more advantageous than a chemical method because of its high regioselectivity, and the simplicity of the reaction and purification processes. Watanabe et al. synthesized various 6-O-acyl ascorbates through condensation of ascorbic acid with fatty acids, such as medium-, long-chain and polyunsaturated fatty acids, using lipases of various origins in a water-miscible organic solvent with low water content (Fig. 1), and examined their properties as an antioxidant and emulsifier (Kuwabara et al., 2003a, 2003b, 2003c, 2005; Watanabe et al., 1999, 2000a, 2001a, 2001b, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2008a, 2008b, 2009a, 2009b, 2010a, 2010b, 2012). In this context, first, the optimal conditions for enzymatic synthesis of acyl ascorbate using an immobilized lipase in a batch reaction system are found. Second, acyl ascorbate is produced continuously using a continuous stirred tank reactor (CSTR) or plug flow reactor (PFR). Moreover, the antioxidant properties of acyl ascorbate against lipid oxidation in bulk and disperse systems are evaluated. Finally, the application of acyl ascorbate to microencapsulation of a lipid is described to demonstrate the effective utilization of acyl ascorbate.

Lipase-catalyzed condensation of ascorbic acid with fatty acid in a microaqueous organic solvent with low water content.

Enzymatic Synthesis of Acyl Ascorbate in Batch and Continuous Reactions Ascorbic acid was esterified with lauric acid in acetonitrile using various lipases of different origins. Chirazyme®L-2 C2 from Candida antarctica (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Germany) immobilized on a macroporous acrylic resin, lipases PS from Pseudomonas cepacia, A from Aspergillus niger, F from Rhizopus oryzae and M from Mucor javanicus (Amano Enzyme Inc., Japan), lipases PL and QL from Alcaligenes sp., AL from Achrobacter sp., OF from C. cylindracea and MY from C. cylindracea nov. sp. (Meito Sangyo Co., Ltd., Japan), and lipase type VII from C. cylindracea (Sigma-Aldrich Fine Chemicals, USA) were used to identify a lipase capable of catalyzing the condensation reaction in the medium (Watanabe et al., 1999). In advance, acetonitrile was dehydrated using molecular sieves at a concentration of 0.2 g/mL-solvent. Twenty milliliters of the dehydrated solvent, 1 mmol of ascorbic acid and 5 mmol of a fatty acid were placed in an amber glass vial with a screw-cap, and then 400 mg of lipase was added. The vial was tightly sealed and immersed in a water-bath. The reaction was conducted at 60°C with vigorous shaking. A portion of the reaction mixture was sampled at appropriate intervals and used for HPLC analysis. Chirazyme®L-2 C2 yielded a sufficient amount of product and lipase PS produced a trace amount of product for 24 h. The other lipases could not produce any products. Chirazyme®L-2 C2 was subsequently used for the synthesis of acyl ascorbate. The lipase-catalyzed condensation of ascorbic acid and lauric acid was executed at various temperatures. The conversion was calculated based on the amount of ascorbic acid added as the limiting reactant. The reaction rate was faster at a higher temperature. The conversion leveled off at 70°C compared to 55 and 60°C. The decrease in the conversion at that temperature was likely due to the denaturation of lipase. Thus, condensation at 60°C was adopted. The transient changes in the conversion of conjugated linoleoyl ascorbate in various organic solvents, such as acetone, acetonitrile, 2-methyl-2-propanol and 2-methyl-2-butanol, were measured (Watanabe et al., 2008b). The conversion was high in the order of acetonitrile, acetone, 2-methyl-2-propanol, and 2-methyl-2-butanol. The reactivity seemed to be in proportion to the polarity of the solvent. Watanabe et al. estimated the equilibrium constant based on concentration, KC, for condensation of mannose and lauric acid in water-miscible solvents using Chirazyme®L-2 C2 (Watanabe et al., 2000b; Watanabe et al., 2001c). The KC value correlated with the relative dielectric constant of the solvent, because the solubility of a hydrophilic substrate such as ascorbic acid was higher in the solvent with the higher relative dielectric constant. The relationships between maximum conversion and the molar ratio for the condensation of ascorbic acid and saturated fatty acid with chain length from 6 to 12 were examined (Watanabe et al., 1999). There was no significant difference in the relationship among the fatty acids tested, as shown in Fig. 2. The maximum conversion was higher at a higher molar ratio. A molar ratio of 5 would be the most appropriate for acyl ascorbate synthesis in the present reaction system, because high conversion and a lower amount of unreacted fatty acid were favorable for the purification process of the product. The gradual decrease in conversion was observed at prolonged reaction time. This was attributed to product degradation to the compounds corresponding to dehydroascorbic acid and 2,3-diketo-gulonic acid (Kurata, 1976). Therefore, too long a reaction time would not be desirable for the efficient production of acyl ascorbate. The water content in the reaction medium is an important factor affecting the conversion, since the enzymatic reaction is reversible (Fig. 1) and water is one of the condensation products. Watanabe et al. estimated the equilibrium constant, KC, for the formation of lauroyl ascorbate through condensation in acetonitrile (Watanabe et al., 1999). KC is defined by

|

Relationships between the maximum conversion and the molar ratio of ascorbic acid to (○) hexanoic acid, (□) octanoic acid, (△) decanoic acid and (▽) lauric acid as fatty acids. The initial concentrations of ascorbic acid and immobilized lipase from C. antarctica were 50 mmol/L and 20 g/L, respectively. The reaction was executed at 60°C in acetonitrile.

Estimation of equilibrium constant, KC, based on concentrations for the synthesis of 6-O-lauroyl ascorbate at 60°C in acetonitrile by 20 g/L immobilized lipase from C. antarctica. The inset shows the effect of initial water content on maximum conversion as the equilibrium value.

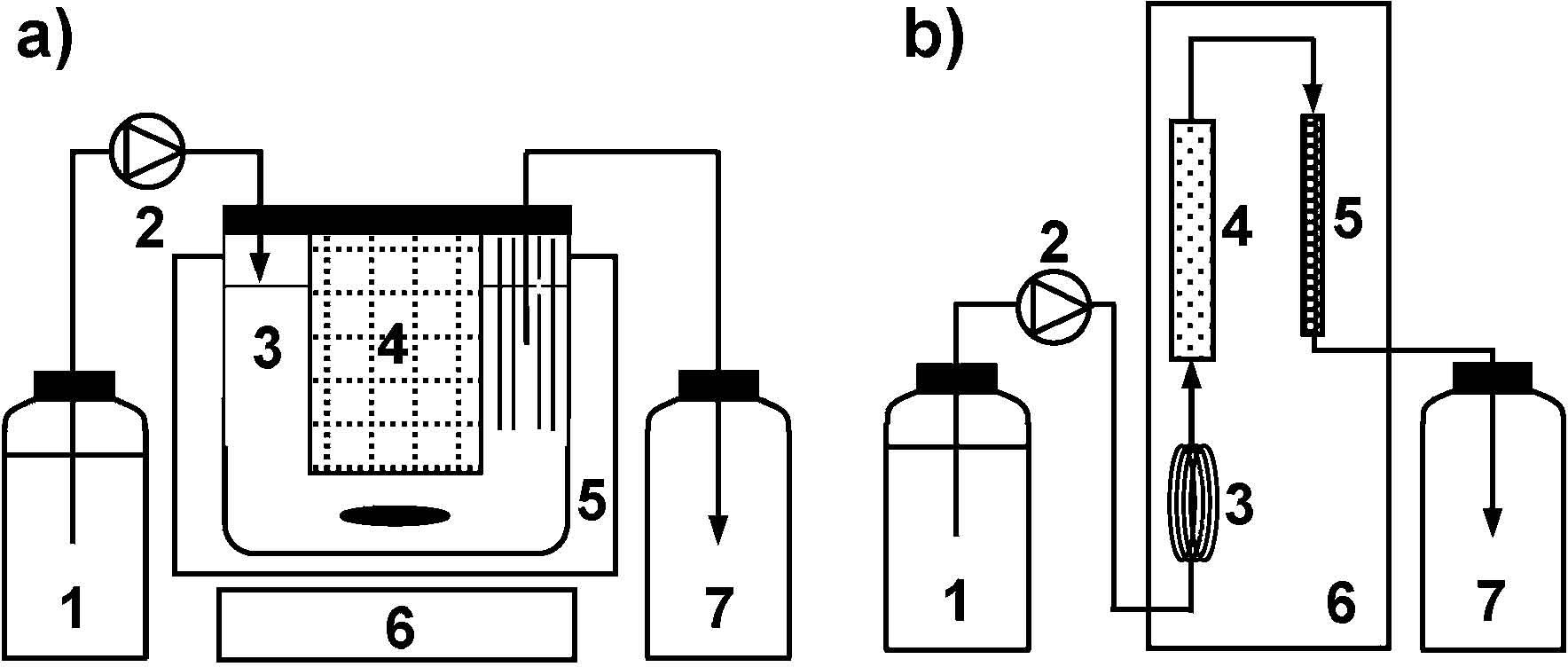

A schematic diagram of a CSTR system for continuous production of acyl ascorbate is shown in Fig. 4(a) (Watanabe et al., 2003). Three grams (dry weight) of an immobilized lipase, Chirazyme®L-2 C2, was packed into a stainless steel basket. The volume of medium in the reactor (85 mmϕ × 90 mm) was 350 mL. At the beginning of the reaction operation, 40 g of ascorbic acid was added to the reactor after removing the upper lid. A fatty acid, such as decanoic, lauric and myristic acids, was dissolved with acetone at a concentration of 200 mmol/L, and the mixture was fed to the reactor at a specified flow rate. The reactor was immersed in a water-bath at 50°C, and the mixture was mixed by a magnetic stirrer in the reactor. The flow rate was varied in the range of 1.5 – 9.9 mL/min for each fatty acid. The reaction was operated at the mean residence time, τ, of 175 min for the long-term production of acyl ascorbates. The long-term operational stability of the immobilized enzyme was examined for the synthesis of decanoyl, lauroyl and myristoyl ascorbates at τ = 175 min. As shown in Fig. 5, the productivity of lauroyl ascorbate for 5 days was constant, and was determined to be ca. 57 g/L-reactor•day. The productivities of decanoyl and myristoyl ascorbates were estimated to be ca. 53 and 66 g/L-reactor•day, respectively. The immobilized enzyme was stable and the reactor was steadily operated for at least 11 days. A scheme of a PFR is shown in Fig. 4(b) (Kuwabara et al., 2003a). Ascorbic acid powders (ca. 40 g) were packed into a cylindrical glass column (10 mmϕ × 150 mm) and Chirazyme®L-2 C2 particles (ca. 1.5 g by dry weight) were packed into a stainless steel column (4.6 mmϕ × 150 mm). These two columns were connected in series with a stainless steel tube. A fatty acid, such as decanoic, lauric, myristic, oleic, linoleic and arachidonic acids, was dissolved in acetone at a concentration of 25 – 250 mmol/L. The fatty acid solution was fed to the column packed with ascorbic acid through the pre-heating coil (1.0 mmϕ × ca. 1.0 m) and then to the immobilized-enzyme column at a specified flow rate. The pre-heating coil and columns were installed in a thermo-regulated chamber at 50°C. Arachidonoyl ascorbate was synthesized for the first day using the reactor system. The fatty acid to be fed was changed to oleic acid, and the synthesis of oleoyl ascorbate was continued for 2 days. Then, linoleic, decanoic, lauric and myristic acids were, in this order, fed to the system to produce the corresponding ascorbates every two days (Fig. 5). For the synthesis of each acyl ascorbate, the τ value was fixed at 5 min. The system could be stably operated for 11 days, and no loss in enzyme activity was observed. The product concentrations in the effluent were in the range of 14 to 17 mmol/L. These product concentrations corresponded to a productivity of 1.6 to 1.9 kg/L-reactor•day, depending on the molecular mass of the product. The productivity in PFR was considerably higher than that in CSTR.

(a) Scheme of a continuous stirred tank reactor for the continuous synthesis of acyl ascorbates; 1: feed reservoir, 2: pump, 3: reactor, 4: basket packed with immobilized lipase, 5: water-bath, 6: magnetic stirrer, 7: effluent reservoir; (b) Scheme of a plug flow reactor; 1: feed reservoir, 2: pump, 3: pre-heating coil, 4: column packed with ascorbic acid, 5: column packed with immobilized lipase, 6: thermo-regulated chamber, 7: effluent reservoir.

Continuous production of (□, ■) decanoyl, (○, ●) lauroyl, (△, ▲) myristoyl, (▼) oleoyl, (◆) linoleoyl, and (◆) arachidonoyl ascorbates using CSTR (open symbols) or PFR (closed symbols) with immobilized lipase from C. antarctica at 50°C. The flow rates were 2.0 mL/min for CSTR and 0.5 mL/min for PFR, respectively. The fatty acid concentration was 200 mmol/L.

Suppressive Effect of Acyl Ascorbate on Lipid Oxidation in Bulk System It was proposed that the entire oxidation process of an n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid and its ester could be expressed by the kinetic equation of the autocatalytic type (Adachi et al., 1995; Ishido et al., 2001). The oxidation processes of linoleic acid with ascorbic acid or saturated acyl ascorbate in bulk system were analyzed by applying a kinetic equation of the autocatalytic type in order to evaluate the antioxidative property of acyl ascorbate (Watanabe et al., 2005). Linoleic acid was mixed with ascorbic acid, octanoyl, lauroyl or palmitoyl ascorbate at a molar ratio (= ascorbate/ linoleic acid) of 0.025, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1 or 0.2, and preserved in a plastic container at a relative humidity of 12%. The container was stored in the dark at 37, 50, 65 and 80°C. Samples were periodically taken, and the amount of unoxidized linoleic acid was measured by GC analysis with an FID according to previous reports (Hashimoto et al., 1981; Minemoto et al., 2002). The oxidative stabilities at 37°C and 12% relative humidity of linoleic acid mixed with ascorbic acid and octanoyl ascorbate at various molar ratios of the ascorbates to linoleic acid indicated that the higher the molar ratio, the more strongly the oxidation of linoleic acid was suppressed in both cases. The addition of the ascorbates elongated the induction period for the oxidation of linoleic acid. Similar results were observed for the oxidation processes of linoleic acid mixed with lauroyl and palmitoyl ascorbates. Octanoyl ascorbate had stronger antioxidative ability than ascorbic acid, and the oxidation with octanoyl ascorbate at a molar ratio of 0.1 was suppressed for at least 130 h. Figure 6(a) shows the oxidation processes of linoleic acid with no additive and that mixed with ascorbic acid or octanoyl, lauroyl, or palmitoyl ascorbate at a molar ratio of 0.05, 80°C and 12% relative humidity. Linoleic acid with no additive was rapidly oxidized. The oxidative stability of linoleic acid was slightly improved by adding ascorbic acid. Octanoyl, lauroyl, and palmitoyl ascorbates retarded the oxidation of linoleic acid much more than ascorbic acid. There seemed to be little difference in the antioxidative ability among the three acyl ascorbates. The entire oxidation process of linoleic acid could be expressed by the following kinetic equation of the autocatalytic type:

|

|

(a) Oxidation processes of (●) linoleic acid without additive and with (□) ascorbic acid, (◇) octanoyl ascorbate, (△) lauroyl ascorbate or (▽) palmitoyl ascorbate at 80°C and a molar ratio of 0.05. Y and t denote the fraction of unoxidized linoleic acid and time, respectively. The solid curves were drawn using the k and Y0 values estimated in Fig. 6(b); (b) Estimation of the rate constant, k, in the rate expression of the autocatalytic type. The symbols are the same as those in Fig. 6(a). The solid curves were drawn based on Eq. 2.

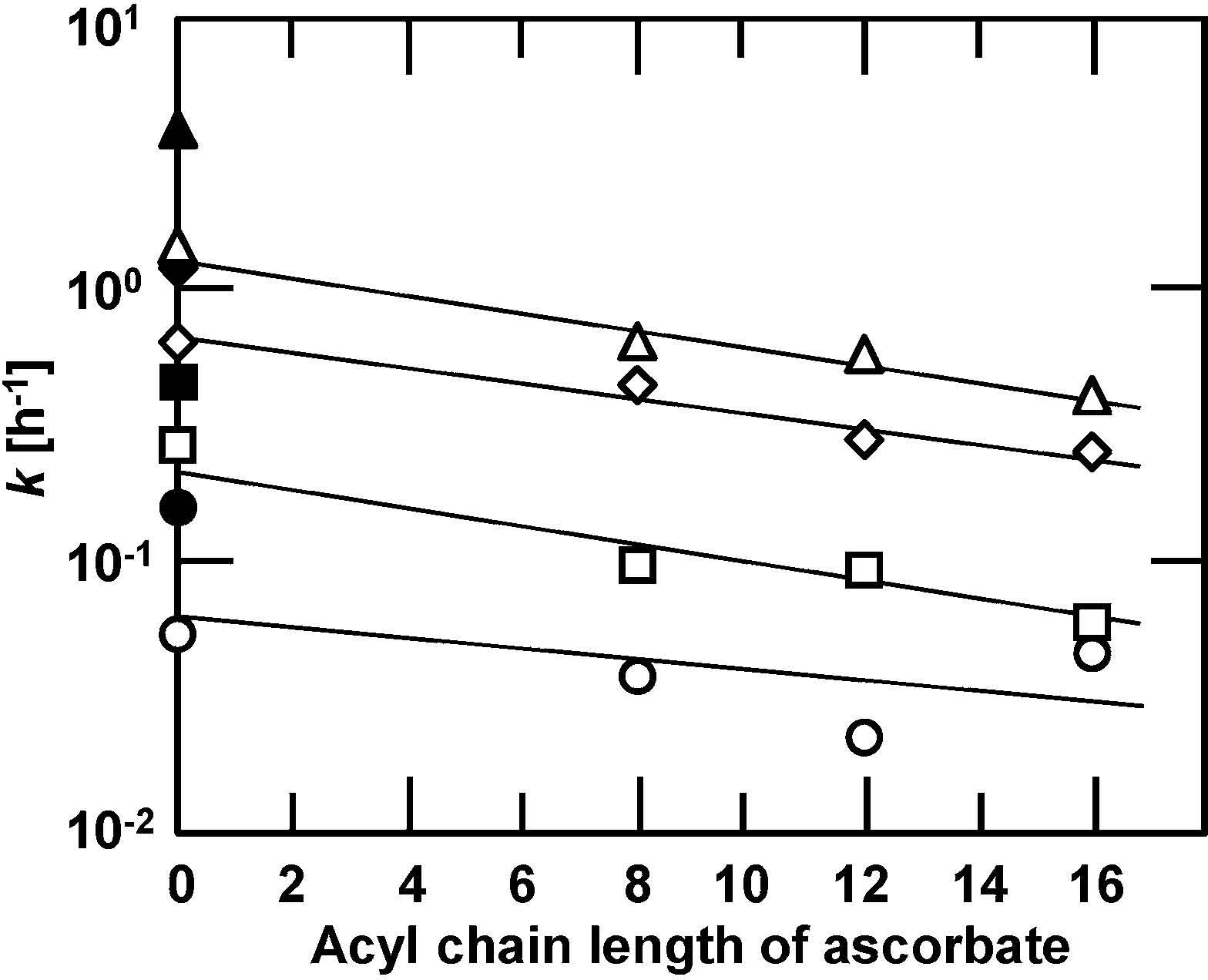

Relationship between the rate constant, k, for the oxidation of linoleic acid at (○) 37, (□) 50, (◇) 65 and (△) 80°C and acyl chain length of ascorbates. Open symbols represent the rate constants for the oxidation with various ascorbates, and closed symbols represent that for no additive.

Antioxidative Behavior of Acyl Ascorbate in Oil-in-water Emulsion Oil-in-water emulsion is a representative disperse system in food processing. The oxidation process of methyl linoleate as an oil phase in the oil-in-water emulsion with ascorbic acid or acyl ascorbate was measured, and their antioxidative properties were evaluated (Watanabe et al., 2010b). In order to elucidate the behavior of the ascorbates in the oil-in-water emulsion, 2,2′-azobis (2-amidinopropane) dihydro-chloride (AAPH) as a hydrophilic proxidant or 2,2′-azobis (2,4-dimethylvaleronitrile) (AMVN) as a lipophilic proxidant was added to the water or oil phase. Five milliliters of a 1.0% (w/v) decaglycerol monolaurate aqueous solution and the same volume of methyl linoleate were added to a tube. AAPH and AMVN dissolved in the water and oil phases at individual concentrations of 1% (w/v) were employed, respectively. Ascorbic acid or octanoyl ascorbate was added to distilled water as the water phase at a specific concentration, whereas the lauroyl or palmitoyl ascorbate was added to the oil phase. The mixture was emulsified using a rotor/stator homogenizer in the tube immersed in ice water to produce the coarse emulsion. The emulsion was circularly passed through a membrane filter to reduce and monodisperse the diameter of the oil droplets. The prepared oil-in-water emulsion was put into an amber glass vial with a screw-cap, and stored in the dark at 40°C with magnetic stirring. The oil phase was sampled from the emulsion at appropriate intervals, and the amount of unoxidized methyl linoleate was determined by GC analysis. The oxidation processes in the emulsion with 1, 10 and 100 µmol/L ascorbates were measured (Fig. 8). The median diameter of the oil droplet in each emulsion was constant at ca. 4.5 µm during the oxidation, indicating that the oxidation processes were appropriate for a stable emulsion. The oxidation kinetics was empirically expressed by the following Weibull equation (Cunha et al., 1998):

|

Oxidative stability of methyl linoleate as an oil droplet at 40°Cin (1) AAPH- and (2) AMVN-containing emulsions with (○) ascorbic acid and (□) octanoyl, (◇) lauroyl, and (△) palmitoyl ascorbates at (a) 1, (b) 10 and (c) 100 µmol/L and (●) without additives. The solid curves were calculated using the estimated kinetic parameters of the Weibull model.

Effect of ascorbate concentration on the rate constant, k, of the Weibull model for the oxidation of methyl linoleate at 40°C in (a) AAPH- or (b) AMVN-containing emulsion with (○) ascorbic acid and (□) octanoyl, (◇) lauroyl, and (△) palmitoyl ascorbates. The broken lines represent the k values for the oxidation without ascorbates.

Suppression of Lipid Oxidation by Application of Acyl Ascorbate to Microencapsulated Lipid Microencapsulation of a lipid with a wall material is a promising technology in the food and other industries (Gibbs et al., 1999). Microencapsulation of polyunsaturated fatty acid or its acylglycerol suppresses or retards its oxidation (Lin et al., 1995; Maloney et al., 1966; Minemoto et al., 2002; Moreau and Rosenberg, 1996). Microencapsulation consists of the emulsification of a core material such as a lipid with a dense solution of a wall material such as a polysaccharide, followed by drying of the emulsion. Spray-drying is commonly used to prepare the microcapsules (Ré, 1998). Application of acyl ascorbate for the microencapsulation of a lipid was examined as an example of the effective use of acyl ascorbate. Linoleic acid mixed with various acyl ascorbates was microencapsulated with maltodextrin (MD) by spray-drying, and the oxidation process was evaluated to determine the antioxidative property of the ascorbate toward the encapsulated linoleic acid (Watanabe et al., 2002). A specific amount of linoleic acid was mixed with each wall material solution. Ascorbic acid or acyl ascorbate, such as octanoyl, decanoyl, lauroyl and palmitoyl ascorbates, was added to the solution, and the mixture was emulsified using a rotor/stator homogenizer. The emulsion was fed into a spray-dryer at 3.0 kg/h and was atomized at ca. 3 × 104 rpm. The air temperatures at the inlet and the outlet were 200°C and 100 – 110°C, respectively. The flow rate of air was ca. 7.5 m3/min. Microcapsules weighed into a flat-bottom glass cup were placed in a plastic container at a relative humidity of 12%. The container was tightly closed and stored in the dark at 37°C. At appropriate intervals, a cup was removed from the container. The unoxidized linoleic acid in the microcapsules was extracted and determined by GC analysis. The ascorbates with acyl chain lengths of 10 or more at a molar ratio of 0.1 to linoleic acid gave emulsions with small median diameters and significantly suppressed the oxidation of the encapsulated linoleic acid. Especially, decanoyl ascorbate was superior both in emulsification ability (small emulsion diameter) and in suppression of the oxidation. When octanoyl ascorbate was used for microencapsulation of linoleic acid, most of the molecules existed in the dehydrated wall material layer and could not scavenge the polyunsaturated fatty acid radicals generated in the oil phase. As the ascorbates, which produced emulsions with small oil droplets, were surface-active, they might more likely locate in the interface between the linoleic acid and the wall material layer. Then, decanoyl ascorbate was used for the microencapsulation of fish oil with three polysaccharides, such as MD, gum arabic (GA), or soluble soybean polysaccharide (SSPS) (Maeda, 2000; Watanabe et al., 2009a). The oxidation processes of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) in encapsulated fish oil were measured, and kinetically evaluated using the Weibull model (Eq. 4). Figure 10 shows the oxidation processes at 65°C and 12% relative humidity of EPA and DHA in fish oil in the bulk and encapsulated with MD, GA, and SSPS. Decanoyl ascorbate was added to the fish oil in the bulk and encapsulated with MD and GA at 0.24 mmol/g-fish oil or SSPS at 0.24, 0.48, and 0.96 mmol/g-fish oil. EPA and DHA in the bulk oil sharply decreased, and the oxidative stabilities of the microencapsules were high in the order of SSPS > GA > MD. This indicates that reducing the oil droplet size, attributable to the emulsifying ability of the wall material, contributed to the high stabilities of EPA and DHA. The encapsulated oil would likely be exposed on the surface of the microcapsule in large droplets (Minemoto et al., 2002). Decanoyl ascorbate suppressed the oxidations of EPA and DHA in each system. The oxidative stabilities of EPA and DHA in the oil encapsulated with SSPS increased with the increasing concentration of decanoyl ascorbate from 0.24 to 0.96 mmol/g-fish oil. The diameter of the oil droplets became constant at the concentrations of decanoyl ascorbate over 0.24 mmol/g-fish oil, and the contribution of decanoyl ascorbate at a high concentration to the oxidative stability of the microencapsulated oil was due to its antioxidative ability but not to its emulsifying ability. Figure 11 shows the relationship between the fractions, which are on day 1 in a bulk oil, on day 2 in a microcapsule with MD, on day 14 in the capsule with GA and SSPS, of unoxidized EPA and DHA in fish oil with decanoyl ascorbate at 0.24 mmol/g-fish oil, and without the ascorbate. The broken line with a slope of 1 in Fig. 11 indicates that decanoyl ascorbate had no suppressive effect on the oxidation of EPA and DHA. It was indicated that the oxidations of both EPA and DHA were suppressed by the addition of decanoyl ascorbate, as the symbols for each system were above the line in Fig. 11, and the antioxidative effect of decanoyl ascorbate for the acids in the system sensitive to the oxidation, such as in a bulk and microcapsule with MD, was high. Therefore, when the wall materials have a low suppressive ability for the oxidation of the encapsulated oil, the addition of decanoyl ascorbate to the oil would be effective.

Oxidation processes at 65°C and 12% relative humidity of (a) EPA and (b) DHA in fish oil. (1) The symbols represent the oxidation processes of EPA and DHA in fish oil (●, ○) in bulk, encapsulated with (▲, △) MD or (■, □) GA. The closed symbols represent the oxidation process without decanoyl ascorbate, and the open symbols with decanoyl ascorbate at 0.24 mmol/g-fish oil. (2) The closed circle, ●, represents the oxidation process of EPA or DHA in fish oil encapsulated with SSPS without decanoyl ascorbate. The open symbols represent the oxidation process with SSPS and decanoyl ascorbate at (△) 0.24, (□) 0.48 and (◇) 0.96 mmol/g-fish oil. The solid curves were drawn based on the Weibull equation.

Relationship between the fractions of unoxidized EPA and DHA in fish oil with and without decanoyl ascorbate at 0.24 mmol/g-fish oil. The closed and open symbols represent the fractions of unoxidized EPA and DHA, respectively, of (●, ○) bulk oil on day 1, (◆, ◇) the oil encapsulated with MD on day 2, (■, □) the oil encapsulated with GA on day 14, and (▲, △) the oil encapsulated with SSPS on day 14.

The application of acyl ascorbate as an antioxidative emulsifier for the microencapsulation of a lipid represents a useful technology for suppressing lipid oxidation. The emulsifier property of the ascorbates changes by altering acyl chain length, and the ascorbates act not only as an antioxidant but also as a proxidant depending on the concentration. Accordingly, the acyl residue as a hydrophobic group and the amount employed are very important for its application in any food system. In future, more detailed information about its efficient usage in various systems is anticipated.

Acknowledgement A part of this work was financially supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) 19780106 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan, and a Grant from Cosmetology Research Foundation, Japan.