2016 Volume 22 Issue 1 Pages 23-29

2016 Volume 22 Issue 1 Pages 23-29

Sensory properties, i.e., firmness, sugar contents, and color, were evaluated for Fuji apples and Niitaka pears irradiated with gamma rays, electrons, or X-rays. The sugar contents in Fuji apples and Niitaka pears were not changed by the three types of radiation. The change in the Hunter's value for radiation doses between 200 and 1,000 Gy was similar for all sources. Although the firmness of the samples decreased remarkably by the phytosanitary irradiation process at doses above 600 Gy, there were no significant differences in this response among the radiation sources. This study identified the applicability of X-ray irradiation as a phytosanitary treatment based on comparisons with gamma-ray and electron-beam irradiation. The effect of X-ray irradiation was similar to that of gamma-ray and electron-beam irradiation with respect to the quality of Fuji apples and Niitaka pears.

The Fuji apple (Malus domestica Borkh. cv. Fuji) and Niitaka pear (Pyrus pyrifolia cv. Niitaka) are major agricultural commodities in Korea. When exporting fresh fruits to foreign markets, one major concern is preventing the introduction or spread of exotic quarantine pests and insects to the receiving area. Thus, phytosanitary treatments are required to disinfest quarantine pests and insects in agricultural commodities. Methyl bromide gas is commonly used for phytosanitary treatment of agricultural commodities, including the apple and pear, owing to its wide spectrum of activity (Fields and White, 2002; Hallman, 2011). Irradiation is more effective than methyl bromide fumigation, which is restricted in many countries owing to possible toxic residues, in controlling insects and pests without undesired effects (Diehl, 2002; Farkas, 2006; Farkas and Andrassy, 1988). In 2003, the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) approved irradiation technology as an international standard for phytosanitary measures in fresh fruits and vegetables (IPPC, 2003). The USDA approved a generic dose of 400 Gy for all insects except pupae and adults in the order Lepidoptera (APHIS, 2002). Fresh fruit must be treated at a minimum dose of 400 Gy for phytosanitary purposes and the maximum dose must not exceed 1,000 Gy.

Food irradiation can be performed using various radiation sources and energy levels: (i) gamma rays produced from radioisotopes cobalt-60 (1.17 and 1.33 MeV) or cesium-137 (0.662 MeV); (ii) electron beams (maximum energy 10 MeV) generated from machine sources; and (iii) X-rays (bremsstrahlung, maximum energy 7.5 MeV) obtained by bombarding a high-density target with a high-power electron beam (Cember and Johnson, 2009). When ionizing radiation passes through matter such as fruit, its energy is absorbed. Absorbed energy leads to interactions between atoms and molecules. X-rays and gamma rays are composed of photons in the electromagnetic spectrum, while electron beams are a particulate radiation with a different energy level (Cleland and Stichelbaut, 2013; Gregoire et al., 2003). Stronger interactions among matter are known to occur for high-energy charged particles emitted from electron beams than for photons of gamma rays and X-rays (Cember and Johnson, 2009; Stewart, 2001). Therefore, the three types of radiation show differences in penetration and different effects on the microbiological and physicochemical qualities of food. Recently, the rising prices of cobalt-60 sources and increasing consumer concerns toward radioactive materials have created a favorable environment for the development of electron beam and X-ray machines. Efficient and powerful electron irradiators have entered the industrial market and have successfully been used for sterilization in other sectors such as medical supplies and cosmetics (Arvanitoyannis, 2010). Food manufacturers in the United States are currently allowed to irradiate raw meat and poultry for the control of microbial pathogens using gamma rays, X-rays, or electron beams (Lutter, 1999).

Previous studies that have compared the use of various radiation sources on foods have mostly examined gamma rays and electron beams. Unfortunately, comparative studies of all three radiation sources have rarely been reported. This study applied gamma rays, electron beams, and X-rays to Fuji apples and Niitaka pears, and the sugar contents, firmness, and color as well as the sensorial properties of each sample were investigated. The objective of this study was to investigate the applicability of X-ray irradiation as a phytosanitary treatment by comparisons with gamma-ray and electron-beam irradiation on the quality of Fuji apples and Niitaka pears.

Sample preparation and irradiation Fuji apple and Niitaka pears harvested from September to October of 2014 were purchased from a local market in Jeongeup, Korea. The average moisture contents in the Fuji apples and Niitaka pears were 84.0 ± 0.6% and 88.9 ± 1.2%, respectively. Fuji apples (60 – 70 mm) and Niitaka pears (90 – 100 mm) of similar size were irradiated with a dose of 0 (control), 200, 400, 600, 800, or 1,000 Gy using one of the designated sources at room temperature (20 – 25°). To ensure uniformity of dose, the samples irradiated with gamma rays were treated by rotating 360° during the irradiation time. The electron beam irradiation was conducted by double-sided irradiation to minimize the variation in penetration depth among the radiation sources, because electron beams has lower penetration ability than those of gamma rays and X-rays. Gamma ray irradiation was performed in a cobalt-60 gamma ray irradiator (AECL, IR-79, MDS Nordion Inc., Ottawa, Canada) at the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute (Jeongeup, Korea) and its source strength was approximately 11.1 PBq. Electron beam irradiation and X-ray irradiation were performed with an ELV-4 electron beam accelerator (10 MeV) and an X-ray linear accelerator (7.5 MeV), respectively, at the EB-Tech Co. (Daejeon, Korea). For each irradiation treatment, the actual doses were determined by placing alanine pellets (Brinker Instruments, Rheinstetten, Germany) at three different heights (top, middle, and bottom positions) within Fuji apples and Niitaka pears. The actual doses were within 5% of targeted doses. After irradiation, the samples were stored at 4°C and used for subsequent experiments.

Sensory evaluation A sensory evaluation was carried out for each sample immediately after irradiation (with gamma rays, electron beams, or X-rays) by ten trained panelists consisting of members of the Team for Radiation Food Science and Biotechnology of the Atomic Energy Research Institute. Both irradiated (200, 400, 600, 800, and 1,000 Gy) and non-irradiated samples were provided to panelists along with an explanation of the purpose of irradiation, and evaluated in terms of appearance, overall acceptance (sweetness, sourness, and crispness), and off-flavor. According to the method described by Civille and Szczesniak (1973), a sensory test was administered to panelists using a 7-point scale, where “7” means the panelist liked the sample extremely and “1” means the panelist disliked the sample extremely. The off-flavor was evaluated on a scale from 1 to 7, where “7” indicates very strong and “1” indicates no off-flavor. The samples were placed on a white plastic dish and labeled randomly with three-digit numerical codes. Sensory evaluations for each group were independently conducted in triplicate.

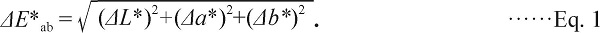

Determination of firmness and Hunter's color values Ten irradiated samples of similar size were selected for an assessment of firmness and Hunter's color values. The peel of each sample was removed for determination of firmness. Firmness was measured at ten locations per fruit using a textural measurement instrument (TA-XT2i, Stable Micro Systems, Surrey, UK) equipped with a 5-kg mechanical load cell. Fruit tissues were compressed with the 11-mm diameter probe. Data were measured with the maximum force of hardness recorded during tissue compression and presented as a force (g). To quantify the rind color of samples in terms of Hunter's L* (lightness), a* (redness), and b* (yellowness), each sample was measured using a spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta CM-5, Tokyo, Japan). For each treatment, ten measurements along the equatorial area of ten samples were obtained. The color difference (ΔE*ab) was calculated from the following equation:

|

Analysis of sugar contents Fructose, glucose, and sucrose in irradiated samples were analyzed through high-performance liquid chromatography (Agilent Technologies 1200 Series, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Crude extracts of Fuji apples and Niitaka pears were obtained with a rotatory squeezer and filtered by a 0.45-µm filter (Millipore, Cork, Ireland). The analytical conditions of the sugar contents were as follows: column, Agilent Zorbax Carbohydrate Analysis Column (4.6 × 250 mm); mobile phase, H2O/acetonitrile (15:85, v/v), 1.0 mL/min; and column temperature, 35°C. As a standard compound, chemicals of fructose, glucose, and sucrose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Statistical analyses Data were analyzed statistically using IBM® SPSS Statistics 21 software for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Analysis of variance and Duncan's multiple range tests with a significance threshold of p < 0.05 were used to compare the differences among mean values.

Sensory evaluation Appearance, overall acceptance, and off-flavor are important quality indicators of irradiated fruit. Sensory scores of non-irradiated and irradiated samples for appearance, overall acceptance, and off-flavor are presented in Table 1. The panelists scored the overall acceptance of 1,000-Gy irradiated samples in the range of 4.7 to 5.7, whereas the non-irradiated samples were scored in the range of 6.6 to 6.8. An off-flavor was detected by most panelists for the samples irradiated at 800 Gy or higher for all sources. The panelists recognized significant dose-dependent overall acceptance and off-flavors (p < 0.05). Statistical analysis of the data revealed that sensory scores of non-irradiated samples were significantly higher than those of irradiated samples for all sources (p < 0.05). However, there were no differences in the individual appearance attributes of Fuji apples and Niitaka pears after irradiation, regardless of the dose and source (Table 1). The effect of the three types of radiation on the sensory properties was indistinguishable for each radiation dose.

| Species | Attributes | Radiation source | Irradiation dose (Gy) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 200 | 400 | 600 | 800 | 1,000 | |||

| Fuji apple | Appearance | Gamma ray | 6.3 ± 0.5Aa | 5.9 ± 1.2Aa | 5.9 ± 1.0Aa | 6.2 ± 0.6Aa | 5.8 ± 0.9Aa | 6.3 ± 1.3Aa |

| E-beam | 6.3 ± 0.5Aa | 6.1 ± 0.6Aa | 6.1 ± 0.6Aa | 6.0 ± 0.7Aa | 6.1 ± 0.6Aa | 6.1 ± 0.6Aa | ||

| X-ray | 6.3 ± 0.5Aa | 6.1 ± 0.6Aa | 6.1 ± 0.6Aa | 6.1 ± 0.3Aa | 6.1 ± 0.3Aa | 6.1 ± 0.3Aa | ||

| Overall acceptance | Gamma ray | 6.6 ± 0.5Aa | 5.7 ± 0.9Aab | 5.4 ± 1.2Aab | 5.6 ± 1.1Aab | 5.3 ± 1.1Ab | 5.2 ± 1.4Ab | |

| E-beam | 6.6 ± 0.5Aa | 6.0 ± 0.5Aab | 5.7 ± 0.5Ab | 5.7 ± 0.5Ab | 5.8 ± 0.8Ab | 5.3 ± 1.0Ab | ||

| X-ray | 6.6 ± 0.5Aa | 6.1 ± 0.6Aab | 6.0 ± 0.7Aab | 5.8 ± 0.7Ab | 5.4 ± 0.7Ab | 5.7 ± 0.7Ab | ||

| Off-flavor | Gamma ray | 1.0 ± 0.0Aa | 1.4 ± 0.7Aa | 1.8 ± 1.2Aab | 1.4 ± 0.7Aa | 1.8 ± 0.4Bab | 2.3 ± 1.2Bb | |

| E-beam | 1.0 ± 0.0Aa | 1.0 ± 0.0Aa | 1.2 ± 0.4Aab | 1.3 ± 0.5Aab | 1.2 ± 0.4Aab | 1.4 ± 0.5Ab | ||

| X-ray | 1.0 ± 0.0Aa | 1.0 ± 0.0Aa | 1.2 ± 0.4Aab | 1.2 ± 0.4Aab | 1.4 ± 0.5Ab | 1.4 ± 0.5Ab | ||

| Niitaka pear | Appearance | Gamma ray | 6.5 ± 0.5Aa | 6.0 ± 0.9Aa | 5.8 ± 1.1Aa | 5.8 ± 0.9Aa | 5.6 ± 0.9Aa | 5.7 ± 0.8Aa |

| E-beam | 6.5 ± 0.5Aa | 5.7 ± 1.1Aa | 5.7 ± 0.7Aa | 5.7 ± 1.3Aa | 5.6 ± 0.8Aa | 5.9 ± 1.4Aa | ||

| X-ray | 6.5 ± 0.5Aa | 5.8 ± 0.9Aa | 5.6 ± 0.8Aa | 6.0 ± 0.7Aa | 5.8 ± 0.9Aa | 6.1 ± 1.2Aa | ||

| Overall acceptance | Gamma ray | 6.8 ± 0.4Aa | 5.8 ± 0.9Ab | 5.8 ± 1.4Ab | 5.1 ± 0.9Abc | 4.3 ± 0.8Ac | 4.7 ± 1.1Ac | |

| E-beam | 6.8 ± 0.4Aa | 5.4 ± 1.0Ab | 5.2 ± 1.2Ab | 5.3 ± 1.3Ab | 5.3 ± 1.0Ab | 4.9 ± 1.4Ab | ||

| X-ray | 6.8 ± 0.4Aa | 5.5 ± 0.7Ab | 5.1 ± 1.1Ab | 5.5 ± 1.0Ab | 5.4 ± 1.0Ab | 5.1 ± 1.4Ab | ||

| Off-flavor | Gamma ray | 1.0 ± 0.0Aa | 1.5 ± 0.9Aab | 1.5 ± 0.7Aab | 1.7 ± 0.8Aab | 1.8 ± 0.8Ab | 1.9 ± 1.0Ab | |

| E-beam | 1.0 ± 0.0Aa | 1.5 ± 0.7Aab | 1.5 ± 0.9Aab | 1.6 ± 0.8Aabc | 1.9 ± 0.6Abc | 2.3 ± 1.1Ac | ||

| X-ray | 1.0 ± 0.0Aa | 1.4 ± 0.5Aab | 1.4 ± 0.5Aab | 1.5 ± 0.7Ab | 1.8 ± 0.4Abc | 2.1 ± 0.6Ac | ||

Data represent mean values ± standard deviation (n = 3).

A–B, a–c Values followed by the same upper case letters within a column and by the same lower case letters within a row are not significantly different by Duncan's multiple range test (p < 0.05).

Determination of firmness The firmness of fruit is a major component of consumer preference for eating quality in apples and pears in addition to appearance and flavor (Kappel et al., 1995; King et al., 2000). Harker (2008) reported that firmness has a universal impact on acceptability and purchase intentions. Consumer acceptability increases with increasing firmness. As the radiation dose increased, the firmness of Fuji apples and Niitaka pears decreased. Multiple comparisons among the individual dose levels for gamma rays, electron beams, and X-rays revealed a significant loss of firmness in Fuji apples at doses of 400, 800, and 1,000 Gy, respectively (p < 0.05) (Table 2). A significant loss of firmness in Niitaka pears was observed at doses of 600, 400, and 1,000 Gy, respectively (p < 0.05) (Table 2). However, there were no differences in the individual radiation sources (Table 2). According to a previous study, the extent of the firmness depends on irradiation and storage time. As irradiation dose and storage time increase, firmness decreases. Numerous studies have reported that the softening of fruits induced by irradiation is associated with the decrease in total pectin content (Gunes et al., 2001; Massey and Smock, 1964). Gamma ray irradiation at doses above 400 Gy decreases the firmness of Fuji apples immediately after irradiation (Al-Bachir, 1999; Gunes et al., 2001; Mostafavi et al., 2012). In this study, the firmness of Fuji apples and Niitaka pears was especially reduced at a dose of 800 Gy (Table 2). The softening of texture in this study was similar to previous findings on apples, citrus, kiwifruits, papayas, and pears (Al-Bachir, 1999; Jung et al., 2014; Kim and Yook, 2009; Miller et al., 2000; Ross and Engeljohn, 2000).

| Species | Radiation sources | Irradiation dose (Gy) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 200 | 400 | 600 | 800 | 1,000 | ||

| Fuji apple | Gamma ray | 6,665 ± 1,036Aa | 6,767 ± 941Aa | 5,899 ± 503Ab | 5,768 ± 373Ab | 5,080 ± 700Ac | 5,270 ± 833Ac |

| Electron beam | 6,665 ± 1,036Aa | 5,883 ± 859Aa | 5,902 ± 615Aa | 5,650 ± 683Aab | 5,337 ± 476Ab | 5,394 ± 478Ab | |

| X-ray | 6,665 ± 1,036Aa | 5,702 ± 554Aab | 5,824 ± 949Aab | 5,589 ± 479Aab | 5,365 ± 479Aab | 5,494 ± 523Ab | |

| Niitaka pear | Gamma ray | 7,642 ± 1,831Aa | 7,043 ± 817Aabc | 7,020 ± 1,281Aabc | 7,242 ± 1,067Abc | 6,350 ± 882Ac | 6,665 ± 1,256Abc |

| Electron beam | 7,642 ± 1,831Aa | 7,564 ± 1,224Aab | 6,264 ± 857Abc | 6,810 ± 995Abc | 6,495 ± 767Ac | 6,132 ± 1,275Ac | |

| X-ray | 7,642 ± 1,831Aa | 7,067 ± 1,481Aab | 7,003 ± 1,710Aab | 6,753 ± 1,190Aab | 6,901 ± 1,468Aab | 6,262 ± 1,503Ab | |

Data represent mean values ± standard deviation (n = 10).

A, a–c Values followed by the same upper case letters within a column and by the same lower case letters within a row are not significantly different by Duncan's multiple range test (p < 0.05).

Color evaluation To compare the rind colors, the ΔE*ab value was calculated using the Hunter's values. A ΔE*ab value in the range of 0 to 0.5 signifies an imperceptible difference in color between the non-irradiated and irradiated samples, 0.5 to 1.5 indicates a slight difference, 1.5 to 3.0 indicates a just noticeable difference, 3.0 to 6.0 indicates a remarkable difference, 6.0 to 12.0 indicates an extremely remarkable difference, and above 12.0 indicates colors of a different shade (Young and Whittle, 1985). Table 3 shows the changes in color of the Fuji apples and Niitaka pears treated with gamma rays, an electron beams or X-rays. The significant differences in the color parameters (L*, a*, and b*) were observed among all the samples (p < 0.05). However, the change in the ΔE*ab value for radiation doses between 200 Gy and 1,000 Gy was similar for all sources. The range of ΔE*ab values for Fuji apples was 1.6 – 2.1 and of particular note, the ΔE*ab values for Niitaka pears were less than 1.5. All Fuji apple samples exposed to gamma ray, electron beam, and X-ray irradiation at doses of up to 1,000 Gy indicated just noticeable differences (1.5 – 3.0) compared to the control (a non-irradiated Fuji apple). All Niitaka pear samples, except the sample exposed to X-ray irradiation at 1,000 Gy, indicated slight differences (0.5 – 1.5) compared to the control (a non-irradiated Niitaka pear). These results demonstrate that decoloring by radiation exposure did not progress. It was reported that gamma ray irradiation at low dose of 900 Gy does not influence the external color of apples and pears (Drake et al., 1999).

| Species | Hunter's value | Radiation source | Irradiation dose (Gy) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 200 | 400 | 600 | 800 | 1,000 | |||

| ‘Fuji’ apple | L* | Gamma ray | 51.7 ± 3.6Ac | 49.5 ± 2.4Cd | 55.9 ± 3.0Ba | 53.7 ± 3.0Ab | 56.2 ± 3.8Aa | 53.8 ± 2.8Ab |

| Electron beam | 51.7 ± 3.6Ab | 55.5 ± 2.5Aa | 51.9 ± 2.6Ab | 55.5 ± 5.3Aa | 53.5 ± 5.0Bab | 53.1 ± 4.5Ab | ||

| X-ray | 51.7 ± 3.6Ac | 53.9 ± 3.3Bab | 54.4 ± 4.7Bab | 55.3 ± 3.2Aa | 55.7 ± 3.5Aa | 53.0 ± 4.1Abc | ||

| a* | Gamma ray | 18.9 ± 4.3Aa | 18.8 ± 2.0Aa | 16.1 ± 3.1Bc | 17.0 ± 2.2Abc | 17.5 ± 3.7Aabc | 18.0 ± 1.8Aab | |

| Electron beam | 18.9 ± 4.3Aa | 18.2 ± 2.7Aab | 18.1 ± 2.1Aab | 17.3 ± 5.2Aab | 17.6 ± 2.4Aab | 16.4 ± 3.0Bb | ||

| X-ray | 18.9 ± 4.3Aa | 18.3 ± 2.8Aa | 17.1 ± 3.1ABa | 17.7 ± 3.3Aa | 14.9 ± 4.3Bb | 18.0 ± 2.8Aa | ||

| b* | Gamma ray | 12.8 ± 4.7Abc | 11.1 ± 2.8Cc | 16.1 ± 2.5Aa | 13.8 ± 2.7Bb | 15.9 ± 3.7Aa | 13.6 ± 3.0Ab | |

| Electron beam | 12.8 ± 4.7Ab | 15.6 ± 2.4Aa | 12.3 ± 2.3Bb | 15.7 ± 4.7Aa | 14.9 ± 3.7Aa | 13.8 ± 4.2Aab | ||

| X-ray | 12.8 ± 4.7Ac | 14.0 ± 2.9Babc | 14.9 ± 4.0Aab | 15.8 ± 3.5Aa | 15.4 ± 3.7Aa | 13.3 ± 3.6Abc | ||

| 1) ΔE*ab | Gamma ray | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.8 | ||

| Electron beam | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.6 | |||

| X-ray | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.7 | |||

| ‘Niitaka’ pear | L* | Gamma ray | 61.6 ± 1.7Ab | 61.4 ± 0.9Ab | 61.3 ± 0.9Bb | 63.1 ± 0.9Aa | 61.7 ± 1.2Bb | 61.1 ± 1.1BB |

| Electron beam | 61.6 ± 1.7Ab | 61.5 ± 1.2Ab | 61.9 ± 1.1ABb | 61.9 ± 2.1Bb | 62.7 ± 1.4Aa | 61.8 ± 1.1Ab | ||

| X-ray | 61.6 ± 1.7Aa | 61.9 ± 1.3Aa | 62.1 ± 1.6Aa | 62.4 ± 1.4ABa | 61.8 ± 0.8Ba | 61.8 ± 1.6Aa | ||

| a* | Gamma ray | 12.7 ± 0.9Abc | 12.6 ± 0.9Abc | 13.0 ± 0.9Aab | 12.3 ± 0.7Bc | 13.2 ± 1.2Aa | 12.7 ± 0.9Abc | |

| Electron beam | 12.7 ± 0.8Aa | 12.6 ± 0.9Aa | 13.2 ± 1.1Aa | 12.8 ± 1.4ABa | 12.7 ± 1.2Aa | 12.6 ± 1.1Aa | ||

| X-ray | 12.7 ± 0.9Aab | 12.9 ± 0.8Aa | 12.0 ± 0.9Bc | 13.0 ± 0.9Aa | 12.8 ± 0.8Aa | 12.1 ± 1.8Abc | ||

| b* | Gamma ray | 30.5 ± 1.9Aa | 30.3 ± 0.9Aab | 30.0 ± 1.1Aab | 30.0 ± 1.2Aab | 29.8 ± 1.3Aab | 29.6 ± 2.01Ab | |

| Electron beam | 30.5 ± 1.9Aa | 29.2 ± 1.1Bb | 29.8 ± 1.1Aab | 28.4 ± 1.1Bc | 29.3 ± 1.4Ab | 28.0 ± 1.5Bc | ||

| X-ray | 30.5 ± 1.9Aa | 29.8 ± 1.1Ab | 29.6 ± 1.5Ab | 30.0 ± 0.9Aab | 29.9 ± 0.8Aab | 28.4 ± 0.9Bc | ||

| 1) ΔE*ab | Gamma ray | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.2 | ||

| Electron beam | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.3 | |||

| X-ray | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.9 | |||

Data represent mean values ± standard deviation (n = 10).

A–C, a–c Values followed by the same upper case letters within a column and by the same lower case letters within a row are not significantly different by Duncan's multiple range test (p < 0.05).

Analysis of sugar contents Fructose, glucose, and sucrose were detected in the Fuji apple and Niitaka pear samples by high-performance liquid chromatography. In the Fuji apple samples, the fructose concentration was the highest, in the range of 68,523 to 78,267 ppm, while the sucrose concentration was the lowest (Table 4). In the Niitaka pear samples, the glucose concentration was the highest, in the range of 45,152 to 54,652 ppm, while the sucrose concentration was the lowest (Table 4). Table 4 shows that three types of radiation at doses of up to 1,000 Gy did not affect the fructose, glucose, or sucrose contents in Fuji apples and Niitaka pears. There were no differences in the individual sugar contents of Fuji apples and Niitaka pears after irradiation, regardless of the dose and radiation source (Table 4). It has been reported that sugar contents in apple and pear are relatively stable under gamma ray irradiation for doses of up to 1,200 Gy (Jung et al., 2014).

| Species | Content | Radiation sources | Irradiation dose (Gy) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 200 | 400 | 600 | 800 | 1,000 | |||

| Fuji apple | Fructose | Gamma ray | 71,322 ± 2,838Aa | 70,555 ± 2,411Aa | 71,062 ± 2,202Aa | 71,803 ± 1,197Aa | 70,782 ± 2,551Aa | 69,669 ± 1,708Aa |

| Electron beam | 71,322 ± 2,838Aa | 68,523 ± 2,709Aa | 73,295 ± 2,296Aa | 71,047 ± 1,632Aa | 78,267 ± 2,848Aa | 71,659 ± 5,314Aa | ||

| X-ray | 71,322 ± 2,838Aa | 69,543 ± 3,071Aa | 69,928 ± 3,041Aa | 73,527 ± 3,065Aa | 70,637 ± 2,550Aa | 70,844 ± 1,902Aa | ||

| Glucose | Gamma ray | 51,675 ± 1,260Aa | 51,706 ± 4,450Aa | 50,114 ± 4,884Aa | 55,448 ± 5,211Aa | 55,746 ± 2,923Aa | 52,476 ± 2,869Aa | |

| Electron beam | 51,675 ± 1,260Aa | 47,653 ± 3,543Aa | 47,758 ± 6,946Aa | 51,076 ± 5,514Aa | 48,845 ± 3,763Aa | 48,992 ± 6,650Aa | ||

| X-ray | 51,675 ± 1,260Aa | 51,298 ± 2,236Aa | 49,715 ± 1,722Aa | 48,836 ± 4,197Aa | 52,668 ± 4,185Aa | 52,352 ± 971Aa | ||

| Sucrose | Gamma ray | 24,105 ± 279Aa | 23,098 ± 2,308Aa | 28,992 ± 2,477Aa | 27,803 ± 6,212Aa | 29,110 ± 2,625Aa | 25,906 ± 1,983Aa | |

| Electron beam | 24,105 ± 279Aa | 27,306 ± 3,608Aa | 28,861 ± 4,555Aa | 30,442 ± 3,861Aa | 30,343 ± 1,549Aa | 30,084 ± 5,937Aa | ||

| X-ray | 24,105 ± 279Aa | 25,152 ± 981Aa | 27,850 ± 2,536Aa | 29,529 ± 1,717Aa | 28,670 ± 4,873Aa | 29,842 ± 4,284Aa | ||

| Niitaka pear | Fructose | Gamma ray | 40,046 ± 3,166Aa | 39,428 ± 2,916Aa | 37,203 ± 1,571Aa | 39,683 ± 7,737Aa | 41,217 ± 3,563Aa | 38,196 ± 3,179Aa |

| Electron beam | 40,046 ± 3,166Aa | 35,192 ± 6,422Aa | 39,559 ± 6,647Aa | 36,035 ± 4,601Aa | 38,789 ± 594Aa | 35,929 ± 3,181Aa | ||

| X-ray | 40,046 ± 3,166Aa | 36,421 ± 3,198Aa | 34,076 ± 6,374Aa | 37,553 ± 4,539Aa | 38,678 ± 1,447Aa | 37,126 ± 2,351Aa | ||

| Glucose | Gamma ray | 49,871 ± 3,327Aa | 47,598 ± 10,741Aa | 52,567 ± 4,687Aa | 48,615 ± 2,490Aa | 49,461 ± 3,975Aa | 46,325 ± 7,933Aa | |

| Electron beam | 49,871 ± 3,327Aa | 47,742 ± 10,484Aa | 54,652 ± 5,801Aa | 50,620 ± 6,594Aa | 54,427 ± 7,179Aa | 51,084 ± 1,736Aa | ||

| X-ray | 49,871 ± 3,327Aa | 51,998 ± 4,587Aa | 50,776 ± 6,551Aa | 50,647 ± 1,901Aa | 52,890 ± 5,711Aa | 45,152 ± 4,493Aa | ||

| Sucrose | Gamma ray | 4,649 ± 393Aa | 3,889 ± 1,394Aa | 3,626 ± 1,049Aa | 3,912 ± 1,406Aa | 4,281 ± 978Aa | 4,910 ± 280Aa | |

| Electron beam | 4,649 ± 393Aa | 3,947 ± 734Aa | 4,819 ± 307Aa | 4,839 ± 531Aa | 3,607 ± 1,327Aa | 4,516 ± 1,316Aa | ||

| X-ray | 4,649 ± 393Aa | 4,883 ± 1,132Aa | 5,042 ± 296Aa | 4,689 ± 197Aa | 4,714 ± 672Aa | 4,458 ± 696Aa | ||

Data represent mean values ± standard deviation (n = 5).

A, a Values followed by the same letters within a row are not significantly different by Duncan's multiple range test (p < 0.05).

In this study, the three types of radiation did not affect the physicochemical quality of Fuji apples and Niitaka pears, except the firmness. The decrease in firmness was dose-dependent. In the sensory test by trained panelists, the overall acceptance and off-flavor of irradiated Fuji apples and Niitaka pears were significantly different than those of the non-irradiated sample (control), but the appearance was not different, regardless of the dose and radiation source. The sugar contents, which are related to sweetness, were also not affected by the three types of radiation for doses of up to 1,000 Gy. Moreover, the decoloring caused by radiation exposure was not manifest in colorimetric values. Color stability against radiation exposure did not differ with respect to radiation dose or source. These results suggest that gamma rays, electron beams, and X-rays can be used as phytosanitary measures without undesired effects in fruits, although firmness was reduced by irradiation. Among the three types of radiation, an optimal source should be chosen considering factors such as sample conditions, production rate, treatment costs, and product quality.

Acknowledgements This research was supported by the Nuclear Research & Development Program of the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation grant funded by the Korean Government (2012M2A2A6011320).