2020 Volume 26 Issue 2 Pages 247-256

2020 Volume 26 Issue 2 Pages 247-256

The aim of this study was to evaluate the bactericidal effects of coffee and chlorogenic acid (CQA) on Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. under low pH conditions simulating gastric juice. E. coli and Salmonella sp. survived at pH 1.5 and pH 3.0, respectively, for 3 h at 37 °C in our experimental conditions. However, 1.0% soluble coffee and 0.5% CQA killed E. coli at pH 1.5, and Salmonella spp. at pH 3.0, respectively. Thus, coffee and CQA showed bactericidal activity under low pH conditions. Although CQA showed stronger bactericidal activity than coffee, considering the content of CQA in soluble coffee, the bactericidal effect of soluble coffee could not be only attributed to CQA. The ethyl acetate fraction prepared from soluble coffee showed the highest activity. As this fraction contained various phenolics as well as CQA, these phenolics may be effective in killing the bacteria under low pH conditions.

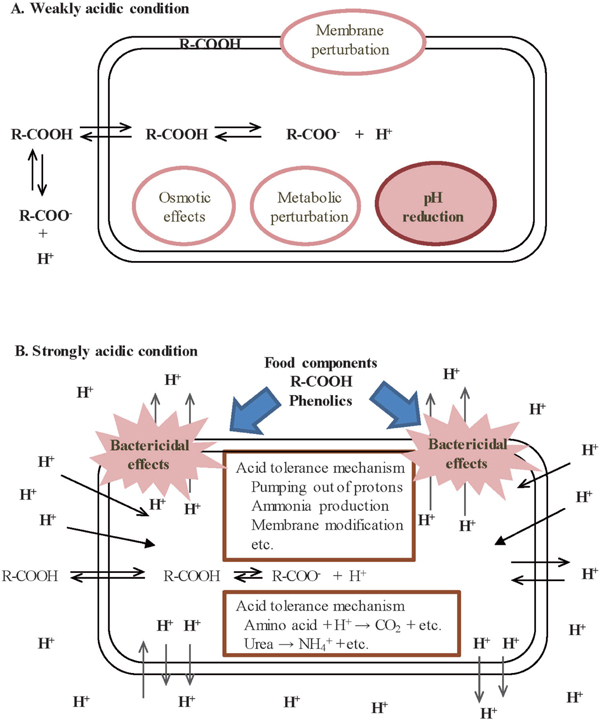

Coffee is one of the world's most popular beverages and is a complex chemical mixture of different compounds including carbohydrates, lipids, nitrogenous compounds, vitamins, minerals, alkaloids, and phenolic compounds (Farah, 2012). The antibacterial activities of coffee against foodborne pathogens such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. have been reported in previous studies (Aeschbacher et al., 1980; Daglia et al., 1994; Mueller et al., 2011). Some components in coffee such as organic acids and phenolics have antimicrobial activities (Almeida et al., 2006; Santana-Gálvez et al., 2017). The reason why organic acids are effective in preventing bacterial growth is that the acids enter cells in the hydrophobic unionized form and then dissociate protons in the cells, lowering the intracellular pH (Fig. 1A; Hirshfield et al., 2003). The pKa values range from 3 to 5 for most organic acids. The antimicrobial activities of organic acids in food are enhanced as the pH of food is lowered, because the unionized form of the acids, which penetrates cells more easily than the ionized form, is increased. (Mani-López et al., 2012). Chlorogenic acid (CQA), which is the major organic acid and phenolic in coffee (Clifford, 1985; Okada et al., 1997; Fukuyama et al., 2009), has antimicrobial effects (Santana-Gálvez et al., 2017). However, weakly acidic conditions such as pH 4–5 were used for examining its antimicrobial effect since most foods are weakly acidic.

Schematics of the mechanism of antimicrobial activity of organic acid or food components on bacteria under weakly acidic conditions as pH 3–7 (A: Hirshfield et al., 2003) and under strongly acidic conditions as pH 1.5–3 (B). The uncharged form of the weak acid such as carboxylic acid (R-COOH) passes across the membrane. The acid dissociates in cells to give a proton (H+) and an anion (R-COO−), which disturbs the normal conditions and/or function of cells (A). Under strongly acidic conditions (B), various acid-tolerance mechanisms function to excrete or reduce protons (Lund et al., 2014). We supposed that when this mechanism was disturbed by organic acid or food components, bacteria couldn't survive under strongly acidic conditions.

On the other hand, we intake various kinds of bacteria including pathogenic and food-poisoning bacteria with food through the mouth. These bacteria are exposed to strongly acidic conditions in the stomach and most are killed. Intragastric pH in healthy persons is about 1.4–2.1 in the fasted state (Dressman et al., 1990; Russell et al., 1993). Depending on the contents of the meal, gastric pH of the fed state is raised to about 4–5 and then gradually returns to the fasted state pH. The normal human stomach averages pH 2 for approximately 2–4 h after it becomes empty (Richard and Foster, 2003; Russell et al., 1993).

Acid tolerance of bacteria is closely related with pathogenesis and food-borne illness (Lund et al., 2014). E. coli and Salmonella spp. can survive at low pH such as pH 2–4 because they have acid tolerance mechanisms to excrete or reduce protons from cells (Beales, 2004; Foster, 2004; Lianou et al., 2017; Lund et al., 2014). We assumed that if food components or organic acids disturbed the acid tolerance mechanism, these bacteria could not survive under low pH conditions such as those in the stomach (Fig. 1B).

Few studies have examined the bactericidal effects of food or food components under such low pH conditions. The bactericidal effects of wine were reported using a model stomach system of pH 2 (Boban et al., 2010; Moretro and Daeschel, 2004), which showed that wine had little effect on E. coli survival whereas Salmonella spp. was undetectable after 2 h. Bactericidal effects of coffee against E. coli and Salmonella spp. have not been examined under lower pH conditions such as a model stomach system.

The purpose of this study was to clarify the bactericidal effects of coffee and CQA against E. coli and Salmonella spp. under low pH conditions simulating gastric juice.

Bacterial strains and conditions E. coli NBRC 14237, E. coli O157:H7 (strains C-13 and C-52; Fukuyama et al., 2009), Salmonella Enteritidis NBRC 3313 and S. Typhimurium DT104 held in our laboratory were used in this study.

Soluble coffee and CQA Soluble coffee samples (Nescafe Gold Blend, Nestle Japan, Tokyo, Japan; MAXIM, Ajinomoto AGF, Tokyo; The BLEND 114, UCC Ueshima Coffee, Kobe, Japan,) were used as coffee powder. 3-Caffeoyl quinic acid hemihydrate (Wako Fujifilm, Tokyo) was used as a standard CQA and abbreviated as 5-CQA. This compound has an ester bond between caffeic acid and a hydroxy group of 5-position of quinic acid in IUPAC system (IUPAC, 1976). This numbering or abbreviation was recommended by Clifford (1985).

Preparation of soluble coffee fraction As shown in Fig. 2, a soluble coffee sample (Nescafe Gold Blend) was fractionated using several extraction solvents with different polarity. At first, 6 g of the sample was ground using mortar and pestle, and then transferred into a centrifuge tube. Diethyl ether (30 mL) was then added. The mixture was shaken with a vortex mixer (Iwaki Glass, Tokyo) for 30 s and allowed to stand for 30 sec. After centrifugation at 3 000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was obtained. This procedure was further repeated four times. The supernatants were combined and evaporated under reduced pressure (Ether frac. in Fig. 2). The residue was similarly extracted with methanol (30 mL) five times. The methanol extracts were combined and evaporated under reduced pressure (Methanol frac.). The residue after methanol extraction was similarly extracted with 80% methanol (30 mL) five times. The extracts were combined and concentrated under reduced pressure (80% MeOH frac.). The residue after 80% methanol extraction was extracted with hot water (30 mL) three times. The hot water extracts were combined (Hot water frac.), adjusted to pH 1.5 with 6 M HCl, and left for 1 h. Formed precipitate was recovered by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The precipitate and supernatant were freeze-dried, respectively, (Acid ppt. frac. and Soluble frac.). The 80% methanol frac. was dissolved in 20 mL water, which was extracted with ethyl acetate (10 mL) five times, and layers of ethyl acetate and water were obtained. The ethyl acetate layer was evaporated under reduced pressure (EtOAc frac.) and the water layer was freeze-dried (Water frac.). Each fraction was dissolved in hot water, and its absorbance at 400 nm and the amounts of 3-, 4- and 5-CQAs were measured with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Each fraction was added to HI broth (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo), which was subjected to the bactericidal test.

Extraction procedure of soluble coffee with solvents. Soluble coffee was extracted with ether, methanol (MeOH), 80%MeOH, and hot water, successively. 80% MeOH frac. was further extracted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc). Hot water frac. was further adjusted to pH 1.5, and then formed precipitate (Acid ppt. frac.) was prepared. Each fraction was subjected to the bactericidal test.

Media for bactericidal test The pHs of HI broth were adjusted with HCl, and then autoclaved at 121 °C in 20 min. Each sample (0.1–1.0% soluble coffee powder, 0.1–0.5% 5-CQA, and 0.125–2% of each soluble coffee fraction, about 1% equivalent of the original soluble coffee powder) was added to the broth. The pH of each broth was adjusted to pH 1.5±0.1 and 3.0±0.1 after adding samples to autoclaved media. One brand of a soluble coffee powder (Nescafe Gold Blend) was mainly used for the bactericidal test. Each broth medium (5 mL) was then dispensed aseptically into a screw-capped tube (16.5 i.d. mm×150 mm).

Inoculum preparation First, a loopful of the bacterial culture from a slant was transferred to a HI agar plate (Eiken Chemical) and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Then, a colony of the bacterial culture was transferred from the plate to 5 mL of HI broth, which was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h with shaking at 110 rpm. After 50 µL of the bacterial culture had been transferred to 5 mL of the HI broth, it was further incubated at 37 °C until the bacteria reached different growth phases of the early exponential, late exponential and stationary phases. The cultures of the early exponential, late exponential and stationary phases were obtained by growing the bacteria for 2–2.5 h of incubation (Optical density at 600 nm; OD600 = 0.4), for 4–8 h (OD600 = 1.3), and for 24 h, respectively. The pre-culture medium incubated at the stationary phase (24 h of incubation) was mainly used for the bactericidal test of soluble coffee samples, CQA, and each coffee fraction. To examine the effect of growth phases of bacteria on the bactericidal activity of coffee, the bacteria at the early exponential and late exponential phases were also used.

The three strains of E. coli and two strains of Salmonella spp. were mixed at a ratio of 1:1:1 and 1:1, respectively. Each mixed culture was appropriately diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% peptone, and then inoculated into 5 mL of the HI broth containing a sample at the rate of about 106 colony forming units (CFU)/mL.

Bactericidal test against E. coli and Salmonella spp. in HI broth under low pH conditions Each HI broth (5 mL) containing a sample and 106 CFU/mL of E. coli or Salmonella spp. was incubated in a test tube closed with a screw cap with shaking at 110 rpm, 37 °C and pH 1.5 or 3.0 for 0.25–3 h. After incubation, the bacteria were washed twice with PBS containing 0.1% peptone, and the bacterial survival number was counted on the agar plate method using HI agar. The detection limits of bacterial number were about 100–101 CFU/mL.

Bactericidal test of coffee fractions against Salmonella spp. in HI broth under low pH conditions HI broth added to different concentrations of a coffee fraction prepared as shown in Fig. 2 was inoculated with about 106 CFU/mL of Salmonella spp., before being incubated at 37 °C for 1.5 h at pH 3.0. As described above, the bacterial count was determined. The bactericidal activity (U) of each coffee fraction was defined as a reduction in viable bacteria of 103 CFU/mL after 1.5 h of incubation from the initial inoculum. The specific bactericidal activity (SBA; U/g of sample) was calculated from the concentrations of an added sample and survival bacterial numbers, while the total bactericidal activity (TBA; U) was calculated as SBA (U/g) × yield (g) of each sample.

Analysis of 3-, 4-, and 5-CQA in coffee Aqueous methanol (methanol : water = 70 : 30; v/v, 20 mL) was added to soluble coffee powder (0.5 g; Nescafe Gold Blend) and heated for 15 min at 70 °C. After centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was obtained. This procedure was further repeated three times. The four supernatants were combined and filled up to 100 mL with 70% methanol. Part of the mixture (10 mL) was evaporated under reduced pressure and dissolved in 2 mL with 70% methanol, which was passed through Chromatodisk (0.45 µm; Juji Field, Tokyo) and then subjected to HPLC. HPLC conditions were as follows: system, Chromaster (Hitachi, Tokyo); column, YMC-Packed R&D ODS-A (4.6 mm i.d. × 250 mm, YMC, Kyoto, Japan); eluent, solution A (CH3CN : 2% acetic acid = 2 : 98, v/v) and solution B (20% CH3CN : 2% acetic acid = 20 : 80, v/v), 100% A for 0–10 min, 0–100% B for 10–50 min and 100% B (v/v) for 50–60 min with a linear gradient; flow rate, 1.0 mL/min; detection, 260, 320 and 400 nm; and quantification, 320 nm. 5-CQA standard was detected at a retention time of about 33 min under this condition. 3-CQA and 4-CQA were detected at respective retention times of about 23 min and 35 min using prepared authentic samples (Murata et al., 1995). The concentrations of 5-CQA in soluble coffee and coffee fractions were calculated from the peak area of the sample of 5-CQA to the corresponding external standard. 3- and 4-CQAs were determined as 5-CQA equivalence.

Specific absorbance and total absorbance Absorbance at 400 nm of each aqueous solution of sample was measured with a spectrophotometer (MultiSpec-1500; Shimadzu, Kyoto). Specific absorbance at 400 nm (SA400) was defined as absorbance at 400 nm of solution of 1 g sample/100 mL. Total absorbance at 400 nm (TA400) was calculated as SA400 × yield (g) of sample from 1 g coffee.

Statistical analysis Statistical analyses were performed using Excel Mac 2011 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) with the add-in software Statcel 3 (OMS, Tokorozawa, Japan). Data were assessed using Pearson's correlation coefficient and one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. The significance level was set at p<0.05. All experiments were conducted in at least triplicate.

Bactericidal effects of soluble coffee against E. coli and Salmonella spp. in HI broth under low pH conditions For the bactericidal test, three strains of E. coli and two strains of Salmonella spp. were, respectively, mixed and used, because the efficiency of the survival of acid shock is strain dependent in both E. coli and Salmonella spp. (Chang and Cronan, 1999, Lianou et al., 2017). Not buffer solutions but HI broths were used for the bactericidal test, because HI broth contains various organic compounds and it is expected that using HI broth is more representative of practical conditions than a buffer solution. First, the bactericidal effect of soluble coffee against E. coli was examined at pH 3.0 and 1.5 (Figs. 3A and 3B). At pH 3.0, E. coli survived for 3 h in HI broth added with and without soluble coffee (Fig. 3A). At pH 1.5, E. coli survived for 3 h in HI broth added with and without 0.1% soluble coffee (Fig. 3B). After 2 and 3 h of incubation at pH 1.5 in HI broth added with 0.5% and 1.0% soluble coffee, the numbers of viable bacteria were significantly decreased compared to the control (no addition of coffee). The viable number 2 h after incubation in the medium added with 1.0% coffee was lower than the detection limit. With increases in the incubation time and the concentration of soluble coffee, the viable number of E. coli was reduced. Thus, the soluble coffee clearly showed bactericidal activity against E. coli under strongly acidic conditions such as pH 1.5, although it did not at pH 3.0. Two other brands of soluble coffee showed similar bactericidal effects at the level of 0.5% and 1.0% at pH 1.5 (data not shown).

Bactericidal effect of soluble coffee against E. coli (A, pH 3.0 and B, pH 1.5) and Salmonella spp. (C, pH 3.0). Mixtures of three strains of E. coli (about 106 CFU/mL) or two strains of Salmonella spp. (about 106 CFU/mL) were incubated at 37 °C for 3 h or 2 h, respectively, in HI broths added without (control, ◆) and with soluble coffee at levels of 0.1% (■), 0.5% (▲), and 1.0% (×). The detection limits of bacterial number were about 100–101 CFU/mL Values within the same column followed by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05; n=3). n.d., not detected.

Next the bactericidal effect of soluble coffee against Salmonella spp. was examined at pH 3.0 and 1.5. Salmonella spp. could not survive in HI broth at pH 1.5 in the presence and absence of soluble coffee even for 15 min. On the other hand, Salmonella spp. survived in HI broth at pH 3.0 added with and without 0.1% soluble coffee for 2 h (Fig. 3C). After 1.5 and 1 h of incubation in HI broth added with 0.5% and 1.0% soluble coffee, the numbers of viable bacteria were significantly decreased compared to the control (no addition of coffee), respectively. After 1.5 h of incubation, Salmonella spp. was not detected in the presence of 1.0% coffee. With increases in the incubation time and the concentration of soluble coffee, the viable number of Salmonella spp. was reduced. Thus, soluble coffee exhibited noticeable bactericidal effects against Salmonella spp. as well as E. coil under low pH conditions.

As shown in Fig. 3, E. coli was more tolerant to lower pH than Salmonella spp.. This result was consistent with previous studies (Lianou et al., 2017; Lund et al., 2014; Spector and Kenyon, 2012), although they did not examine the effects of coffee. Intragastric pH in the fasted state is usually about pH 1.4–2.1 (Dressman et al., 1990; Russell et al., 1993). Therefore, drinking coffee under low pH conditions such as fasted state may effectively kill these bacteria. However, we do not know whether drinking coffee while eat a meal is effective because the intragastric pH usually rises to about 5–6 depending on the content of the meal. Because the concentration of coffee in the stomach will be diluted by when food is consumed, the influence of the dilution on the bactericidal effect of soluble coffee against these bacteria should be also considered. Although acidity is the main cause of bacterial death in the stomach, pepsin is known to promote killing bacteria at low pH in gastric juice (Zhu et al., 2006). It seems to be necessary to examine the synergistic effect of pepsin in HI broth on the bactericidal effect of coffee.

E. coli and Salmonella spp. have similar but different survival systems for acid conditions (Beales, 2004; Foster, 2004; Lianou et al., 2017; Lund et al., 2014). The difference in the effects of pH on the survival of E. coli and Salmonella spp. are considered to be due to the difference in acid resistant systems. In this study, E. coli and Salmonella spp. were directly inoculated to the liquid media adjusted to pH 1.5 and 3.0, respectively. However, it was reported that E. coli and Salmonella spp. became more resistant to acidity when they were adapted to mildly acid pH conditions such as pH 4.5–5.8 (Foster and Hall, 1990; Lin et al., 1995). It will be necessary to examine the effects of preincubation at mildly acidic conditions on the bactericidal activity of coffee.

Effects of different growth phases of E. coli and Salmonella spp. on the bactericidal effects of soluble coffee under low pH conditions Bacteria in different growth phases exist in food, and they show different acid tolerances (Alvarez-Ordonez et al., 2010; Bearson et al., 1997; Benjamin and Datta, 1995; Chang and Cronan, 1999; Richard and Foster, 2003). The bactericidal effects of soluble coffee against three different growth phases, the early exponential, late exponential, and stationary phases, of E. coli and Salmonella spp. were examined.

As shown in Fig. 4, E. coli at the late exponential and stationary phases survived for 3 h in HI broth added with and without 0.1% soluble coffee but most E coli were killed at 3 h of incubation in HI broth added with 0.5% soluble coffee. In HI broth added with 1% soluble coffee, E. coli at the late exponential and stationary phases were not detected 1 h and 2 h after incubation, respectively. E. coli at the early exponential phase was killed at 1 h of incubation in HI broth added with and without 0.1% soluble coffee, and killed at 0.25 and 0.5 h of incubation in HI broth added with 1.0 and 0.5% soluble coffee, respectively. These results showed that E. coli at the early exponential phase were the most sensitive to the strongly acidic condition and that E. coli at the stationary phase were the most resistant to the bactericidal effects of coffee.

Effects of the growth stages of E. coli on the bactericidal effect of soluble coffee. Cultures of the early exponential (◆), late exponential (■), and stationary phases (▲) were obtained by growing the bacteria for 2–3 h, 4–8 h, and 24 h of incubation, respectively. Mixtures of three strains of E. coli (about 106 CFU/mL) at each growth stage were inoculated into HI broths added without (A) and with soluble coffee at levels of 0.1% (B), 0.5% (C), and 1.0% (D) at pH 1.5, which were incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. The detection limits of bacterial number were about 100–101 CFU/mL. Values within the same column followed by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05; n=3). n.d., not detected.

Similarly, we examined the effects of growth phases of Salmonella spp. on the bactericidal activities of soluble coffee in HI broth at pH 3, as the bacteria were killed at pH 1.5 without soluble coffee. As shown in Fig. 5, Salmonella spp. at the late exponential and stationary phases survived for 2 h in HI broth added with and without 0.1% soluble coffee, while the bacteria were not detected 1.0 and 1.5 h after incubation in HI broth added with 0.5 and 1.0% soluble coffee, respectively. As well as E.coli, Salmonella spp. at the early exponential phase were the most sensitive to the strongly acidic condition. Salmonella spp. at the late exponential and stationary phases were more resistant to the bactericidal effects of coffee than those at the early exponential phase.

Effects of the growth stages of Salmonella spp. on the bactericidal effect of soluble coffee. Cultures of the early exponential (◆), late exponential (■), and stationary phases (▲) were obtained by growing all strains for 2–3 h, 4–8 h, and 24 h of incubation, respectively. Mixture of two strains of Salmonella spp. (about 106 CFU/mL) at each growth stage were inoculated into in HI broths added without (A) and with soluble coffee at levels of 0.1% (B), 0.5% (C), and 1.0% (D) at pH 3.0, which were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The detection limits of bacterial number were about 100–101 CFU/mL. Values within the same column followed by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05; n=3). n.d., not detected.

E. coli and Salmonella spp. during the exponential phase were quite acid sensitive. However, they became acid resistant upon entry into the stationary phase. The results in this study agreed with previous studies (Alvarez-Ordonez et al., 2010; Bearson et al., 1997; Benjamin and Datta, 1995; Chang and Cronan, 1999; Richard and Foster, 2003), although the effects of coffee were not examined in the previous studies. The development of acid tolerance in both E. coli and Salmonella spp. was highly influenced by stage of growth. However, with increases in the incubation time and the concentration of soluble coffee, the viable numbers of E. coli and Salmonella spp. in all phases of growth were reduced. The addition of 0.5 and 1.0% soluble coffee killed E. coli and Salmonella spp. at all growth phases effectively under low pH conditions.

Bactericidal effects of CQA against E. coli and Salmonella spp. under low pH conditions CQA is the major phenolic and organic acid in coffee (Clifford, 1985 Okada et al., 1997; Fukuyama et al., 2009). Therefore, bactericidal activities of CQA against E. coli and Salmonella spp. were examined using the stationary phase of these bacteria. E. coli and Salmonella spp. grew in HI broth added with and without 0.1–0.5% CQA at pH 7 similarly (data not shown); however, CQA showed bactericidal activities against E. coli at pH 1.5 and Salmonella spp. at pH 3.0. Figure 6A showed that 0.5% CQA showed a significant bactericidal effect against E. coli compared to the control after 1, 2 and 3 h of incubation, although 0.1 and 0.2% CQA did not. Similarly, 0.5% CQA showed a significant bactericidal effect against Salmonella spp. (Fig. 6B). E. coli and Salmonella spp. were not detected 3 h and 2 h after incubation in the presence of 0.5% CQA at pH 1.5 and pH 3.0, respectively. These results showed that 0.5% CQA killed the bacteria with an increase in incubation time under low pH conditions. It was reported that 0.5 mg/mL of CQA slightly inhibited the growth of E. coli and Salmonella at pH 7 (Puupponen-Pimia et al., 2001; Shen et al., 2014). The bactericidal effect of 2.5 mM CQA against E. coli has been examined at higher pH values, such as pH 4-5 (Kabir et al., 2014), than in the present study. The bactericidal effect of CQA on Salmonella spp. has not been examined yet. It was suggested that CQA was bound to the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, disrupted the membrane, exhausted the intracellular potential, and released cytoplasm macromolecules, which led to cell death (Lou et al., 2011), but the action mechanism of CQA is still not understood.

Bactericidal effects of chlorogenic acid (CQA) on E. coli (A) and Salmonella spp. (B). Mixtures of three strains of E. coli (about 106 CFU/mL) or two strains of Salmonella spp. (about 106 CFU/mL) were incubated in HI broths added without (control, ◆) and with CQA at levels of 0.1% (■), 0.2% (▲), and 0.5% (×) at pH 1.5 or 3.0, respectively, at 37 °C for 2–3 h. The detection limits of bacterial number were about 100–101 CFU/mL. Values within the same column followed by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05; n=3). n.d., not detected.

Green coffee beans contain about 7% CQAs, and 30–50% of them are decomposed during roasting of coffee beans (Farah, 2012). The amounts of CQAs in coffee, which are influenced by the kinds of coffee beans and roasting, range from 5.3 mg/g to 17.1 mg/g in regular coffee (Fujioka and Shibamoto, 2008; Ky et al., 2001). Among CQAs, 5-CQA is present at the highest level, ranging from 2.1 mg/g to 7.1 mg/g of coffee, and comprising 36–42% of total CQAs in regular coffee. 3-, 4-, and 5-CQA (total mono-caffeoylquinic acids) is present ranging from 4.9 mg/g to 15.1 mg/g coffee.

5-CQA and total mono-caffeoylquinic acids of soluble coffee used for the bactericidal test in this study were quantified with HPLC. The amounts of 5-CQA and total mono-caffeoylquinic acids in the soluble coffee sample were about 4.5 mg/g (0.45%) and 12.6 mg/g (1.26%), respectively. The soluble coffee sample used in this study contained about 1% total mono-caffeoylquinic acids. Here, we showed that 0.5% soluble coffee reduced viable cells of E. coli during incubation at pH 1.5 (Fig. 3), but 0.5% soluble coffee contained only 0.002% (0.5 × 0.0045 = 0.00225) of 5-CQA or 0.006% (0.5 × 0.0126 = 0.0063) of mono-caffeoylquinic acids. From these results, the contributions of 5-CQA and mono-caffeoylquinic acids to the total bactericidal effect of soluble coffee were estimated about 0.4% and 1.2% ((0.002 and 0.006)/0.5 × 100), respectively. This estimation showed that the total bactericidal activity of coffee could not be explained by CQA and mono-caffeoylquinic acids alone. It is reported that the synergistic effect of organic acids and ethanol is responsible for the antibacterial effect of wine at low pH (Moretro and Daeschel, 2004). Mixtures of acids could show stronger antimicrobial activity than a single organic acid (Lucera et al., 2012). Coffee contains various chlorogenic acid-related compounds such as feruloylquinic, dicaffeoylquinic, and caffeoyl-feruloylquinic acids. These compounds might be effective or synergistic in killing E. coli and Salmonella spp. under low pH conditions.

Bactericidal effects of coffee fractions against Salmonella spp. under low pH conditions To characterize bactericidal components in soluble coffee, it was fractionated as shown in Fig. 2. Figure 7 showed the ratio of yields (A) and total color intensity (B) of each fraction. From 1 g of soluble coffee, about 0.38 g of 80% MeOH frac. and about 0.38 g of Soluble frac. were obtained. Various products of the Maillard or browning reaction are formed as green coffee beans are roasted, and coffee melanoidins were reported to have antibacterial and bactericidal activities (Rufián-Henares et al., 2009). Therefore, the colors of coffee fractions were also measured. The total color intensity of 1 g soluble coffee estimated by absorbance at 400 nm was 6.9, while those of 80% MeOH frac. and Soluble frac. were 2.5 and 3.2, respectively. These results showed that these two fractions were the major fractions from both of quantity and color. There was no definite difference in the specific absorbance that was defined as the color intensity divided by the yield among fractions. From these results, it is suggested that the major fractions in quantity contributed mainly to the total color of coffee.

Yields (A), pigment distribution (B), and bactericidal activities against Salmonella spp. (C) of fractions prepared from soluble coffee. Each fraction was prepared as shown in Fig. 2. Specific absorbance (SA400) was defined as absorbance at 400 nm of a solution of 1 g sample/100 mL. Total absorbance (TA400) was calculated by SA400 × yield (g/g coffee). TA400 of 1 g of soluble coffee (6.9) was set as 100% of TA400 in B. One unit of the bactericidal activity (U) was defined as a reduction in viable bacteria of 3 log CFU/mL after 1.5 h of incubation in this assay condition. Bactericidal activity of each fraction was calculated by specific bactericidal activity (U/g) × yield (g) of fraction. The bactericidal activity of 1 g of soluble coffee (880 U) was set as 100% of bacterial activity in C.

Then, the bactericidal effect of each coffee fraction against Salmonella spp. was examined in a HI broth at pH 3.0. To estimate bactericidal effects qualitatively, one unit (U) of bactericidal activity was here defined as the reduction of 3-log of the bacteria in this assay condition. Figure 7C shows the total bactericidal activities of soluble coffee and each fraction. The total activity of soluble coffee (1 g) was about 880 U, which was set to 100% in Fig. 7C, while those of MeOH frac., 80% MeOH frac., and Soluble frac. in Fig. 2 are 77, 310, and 140 U, respectively, showing that the 80% MeOH fraction was the major fraction for bactericidal activity. Soluble frac., one of the major color fractions, did not show strong bactericidal activity. Acid ppt frac. prepared from Soluble frac. by acid-precipitation seemed to be coffee melanoidins because this fraction is composed of water-soluble acidic brown polymers. However, this fraction did not show definite bactericidal activity. On the other hand, EtOAc frac. obtained from 80% MeOH frac. by extracting with ethyl acetate showed the highest total activity (47% of the total activity) and specific bactericidal activity (4,700 U/g). The specific bactericidal activities of other fractions were lower than that of soluble coffee (data not shown). These results suggest that substances in EtOAc frac. contributed to killing Salmonella spp. and that colored substances such as melanoidins did not kill them efficiently. Next, the amounts of 3-, 4-, and 5-CQAs in soluble coffee and each fraction were measured with HPLC. MeOH frac. and 80% MeOH frac. contained about 30% and 60–70% of mono-caffeoylquinic acids, that are the sum of 3-, 4-, and 5-CQAs, in soluble coffee, respectively. EtOAc frac. showing the highest bactericidal activity contained about 2.3 mg of 5-CQA/g soluble coffee and 5.5 mg of mono-caffeoylquinic acids/g soluble coffee. From these results it was suggested that compounds other than 5-CQA and mono-caffeoylquinic acids existing in EtOAc frac. contributed to killing the bacteria under acidic conditions. The bactericidal activities of some components or CQA-related compounds such as dicaffeoylquinic and caffeoyl-feruloylquinic acids in EtOAc frac., and the synergistic effects of coffee components should be examined in the future.

Here we clearly showed that soluble coffee and CQA exhibited significant bactericidal effects against E. coli and Salmonella spp. under low pH conditions simulating gastric juice. With increases in the concentrations of soluble coffee and CQA, the bactericidal effects increased. Drinking coffee under low pH gastric conditions may kill these bacteria effectively. CQA also exhibited significant bactericidal effects against E. coli and Salmonella spp.. However, considering the concentration of CQA in soluble coffee, the contribution of CQA to the bactericidal activities of coffee seemed to be partial. Melanoidins or colored substances of coffee also did not seem to contribute to intense bactericidal activities of coffee. The bactericidal activities of CQA-related compounds such as dicaffeoylquinic and caffeoyl-feruloylquinic acids, and the synergistic effects of coffee components should be examined.