2013 Volume 55 Issue 4 Pages 234-243

2013 Volume 55 Issue 4 Pages 234-243

Objectives: This study among Japanese dual-earner couples examined the independent and combined associations of work-to-family conflict (WFC) and family-to-work conflict (FWC) with psychological health of employees and their partners and the relationship quality between partners. Methods: The matched responses of 895 couples were analyzed with logistic regression analysis to examine whether there were differences among the four work-family conflict groups (i.e., no conflict, WFC, FWC and both conflicts groups) in terms of own psychological distress, social undermining (i.e., negative behaviors directed toward the target person) reported by partners and partner's psychological distress. The no conflicts group was used as the reference group. Results: The both conflicts group had the highest odds ratios for own psychological distress and social undermining towards the partner for both genders. In addition, for husbands, the both conflicts group had the highest odds ratio for partner's psychological distress, whereas for wives, it did not. Conclusions: Dual experiences of WFC and FWC have adverse associations with psychological health of employees and relationship quality between partners of both genders. In addition, dual experiences in husbands have an adverse association with psychological health of their partners (i.e., wives), whereas this is not the case for wives.

(J Occup Health 2013; 55: 234-243)

Research on predictors of employee health has grown considerably over the past two decades. Most research has focused on predictors that are intrinsic to the work environment, including job demands, job resources (e.g., job control, workplace support), effort-reward imbalance and exposure to physical hazards1-3). However, in recent years, social trends such as increasing participation by women in the workforce and a greater number of dual-earner families have created the potential for interference or conflicts to occur between peoples' work and non-work lives4-7).

The present study among Japanese dual-earner couples with preschool children focused on the association of conflict between work and non-work lives with well-being by using a large community sample. Specifically, we examined whether employees' dual experiences of work-to-family conflict (WFC) and family-to-work conflict (FWC) have more adverse associations than separate experiences of WFC or FWC with regard to their own and their partner's psychological health and relationship quality between partners.

Work-family conflict and psychological healthWork-family conflict is defined as “a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect, such that participation in one role makes it difficult to participate in the other”8). This definition of work-family conflict implies a bidirectional relation between work and family life in such a way that work can interfere with family life (i.e., work-to-family conflict: WFC) and family life can interfere with work (i.e., family-to-work conflict: FWC)1).

Ever since the construct of work-family conflict was introduced, a large body of literature has explored the relations of work-family conflict with (health) outcomes, and bivariate associations of WFC and FWC with psychological health, physical health, and health-related behaviors have been examined9, 10). However, in reality, it is less likely that people experience either type of conflict (i.e., WFC or FWC) exclusively. Rather, they often experience both types of conflicts simultaneously because WFC and FWC have a positive reciprocal relationship11). Indeed, the meta-analytic review of Byron12) showed that both types of conflicts are positively related (r=0.48). Hence, it is important to examine the combined as well as independent associations of WFC and FWC with well-being in employees and their partners.

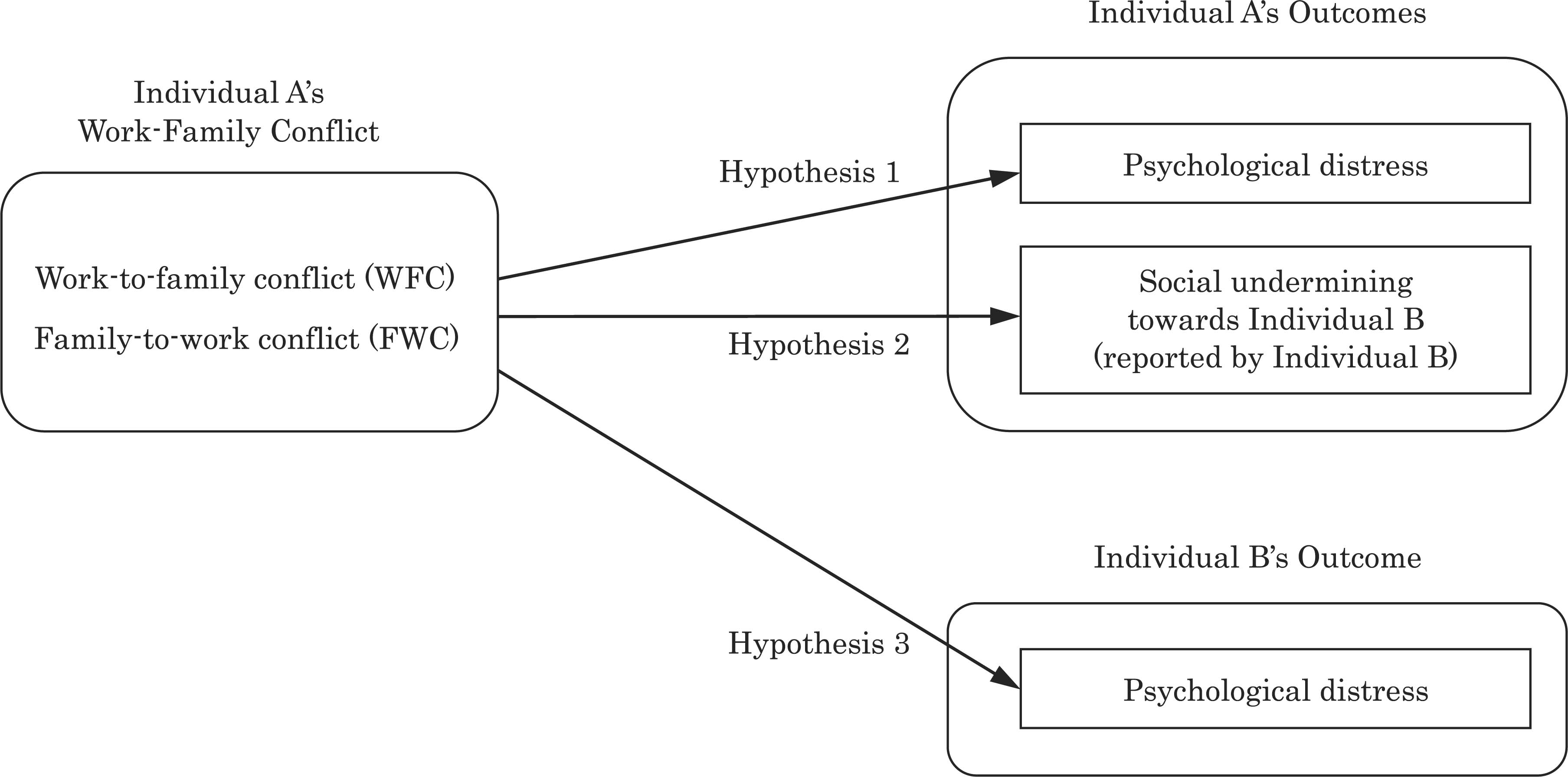

The relationship between work-family conflict and health outcomes might be explained by COR theory, which asserts that an individual aspires to preserve, protect and build resources such as objects, conditions, personal characteristics or energies13). The COR is a relevant theoretical framework, as it integrates work and family by the concept of resources that join these different domains in a common economy in which resources are exchanged13). According to COR theory, stress occurs when individuals are threatened with resource loss, actually lose resources or fail to gain resources following resource investment. Managing inter-role relationships leads to stress because resources can be lost in the process of juggling both work and family roles14). Thus work-to-family or family-to-work conflict represent the experience of threat or actual loss of resources (e.g., less time for sleep and leisure activities at home and less time for breaks and lunch at the workplace) and therefore can result in adverse psychological and/or physical health and impaired functioning in either domain. On the basis of this theory, we can predict that people suffer from more severe psychological distress if they experience both WFC and FWC at the same time (Hypothesis 1). This is because the combination of both experiences requires more effort to deal with, and the result may be a more severe depletion of resources.

Work-family conflict and relationship quality between partnersAs work-family conflict represents threatened or actual loss of resources, it may deteriorate an individual's functioning and behavior in either domain. We focus specifically on the association of work-family conflict with relationship quality between partners. Considerable research evidence now demonstrates that individuals who are psychologically distressed are more likely to withdraw from others or be hostile and irritable in their interactions with others, including family members7, 15-17). In line with this, we focus on social undermining as poor relationship quality between husband and wife. Social undermining is theorized to consist of behaviors directed toward the target person and to display (a) negative affect, (b) negative evaluation of the person in terms of his/her attributes, actions, and efforts (criticism) and (c) behaviors that compromise or hinder the attainment of instrumental goals18).

Previous studies on family processes strongly suggest that the experience of WFC and its accompanying frustration, tension or psychological distress lead an individual to initiate or exacerbate a negative interaction sequence with their partner19, 20). Given that people feel more psychological distress when they experience both WFC and FWC simultaneously according to COR theory, we can predict that dual experiences of WFC and FWC will be more strongly related to poor relationship quality (i.e., social undermining towards the partner) (Hypothesis 2).

Work-family conflict and psychological health of partnersNot only should work-family conflict have an association with relationship quality between partners, it might also have an association with the psychological health of one's partner. This interindividual transmission of stress or strain between closely related persons is referred to as crossover19, 20). Whereas work-family conflict or spillover is a within-person across-domains transmission of strain from one area of life to another, crossover involves transmission across individuals. For instance, Shimazu et al.17) showed that a husband's (wife's) WFC led to a poor relationship quality (reduced social support and increased social undermining towards the partner), which resulted in his (her) partner's diminished health (i.e., psychological distress and physical complaints). Thus, given that a person exhibits more social undermining towards their partner when that person experiences both WFC and FWC simultaneously according to COR theory, we can predict that dual experience of WFC and FWC will be more strongly related to psychological distress of the partner (Hypothesis 3).

The current studyIn the current study, we examined the abovementioned three hypotheses by using a large community sample; that is, we examined whether employees' dual experiences of WFC and FWC have stronger associations than separate experiences of WFC or FWC with regard to their own psychological distress (Hypothesis 1), social undermining behaviors towards their partner (Hypothesis 2), and their partner's psychological distress (Hypothesis 3). Figure 1 shows the framework of this study.

The framework of this study.

The present study is a part of the Tokyo Work-family INterface (TWIN) study, a large two-wave cohort study with a one-year time interval21). The TWIN study aims to examine the intraindividual (i.e., spillover) and interindividual (i.e., crossover) processes of well-being among all dual-earner couples with preschool children in the Setagaya Ward, Tokyo, Japan. Setagaya Ward has the seventh highest socioeconomic status among the 62 municipalities in metropolitan Tokyo, with an average annual taxable income of ¥ 4,989,074 (i.e., approximately US $ 61,880) per taxpayer in 200922). In the present study, we analyzed the first wave of data collected in 2008.

Working partners were approached through the nursery schools where they brought their children. With the help of the Child-raising Assistance Department of Setagaya Ward in Tokyo, a letter was sent to all directors of nursery schools in this ward to approach all dual-earner couples there. The letter explained the aims, procedure and ethical considerations of the study. Eighty-one out of all 82 schools agreed to participate. The data were collected by means of two questionnaires. The researchers distributed two identical questionnaires, one for each partner, through the nursery schools. Respondents returned their questionnaires in closed, prestamped envelopes to a researcher at the University of Tokyo. Of the 8,964 questionnaires distributed, 2,992 were returned, resulting in a response rate of 33.4%. The participants in the present study were 1,790 parents (i.e., 895 couples) who met the following five criteria: (a) had at least one child six years of age or younger, (b) had a partner (neither widowed nor divorced status), (c) lived in a dual-earner household, (d) were employed at least 20 hours per week according to the criteria of Frone (2000)1), and (e) answered all the items of the variables.

The whole procedure followed in the present study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo.

Measures 1) Work-family conflictWork-family conflict (WFC and FWC) was measured using the corresponding subscales of the Survey Work-home Interaction-NijmeGen (SWING)23). The SWING captures WFC with eight items, while FWC is captured with four items. Example items are “How often does it happen to you that your work schedule makes it difficult for you to fulfill your domestic obligations?” (WFC) and “How often does it happen to you that you have difficulty concentrating on your work because you are preoccupied with domestic matters?” (FWC). Items are scored on a four-point scale, from (0) “never” to (3) “always.” The reliabilities of the scales were good; Cronbach's alphas were 0.86 (husbands) and 0.85 (wives) for WFC and 0.81 (husbands) and 0.77 (wives) for FWC. The respondents were classified into four quadrant groups using the median split for the scores on WFC and FWC in the current study: (1) the no conflict group, which scored low for both WFC and FWC (n=323 for husbands and n=327 for wives); (2) the WFC group, which scored high for WFC but low for FWC (n=136 for husbands and n=202 for wives); (3) the FWC group, which scored high for FWC but low for WFC (n=190 for husbands and n=146 for wives); and (4) the both conflicts group, which scored high for both WFC and FWC (n=246 for husbands and n=220 for wives).

2) Psychological distressThe Kessler 6 (K6) questionnaire was employed to assess psychological distress24, 25). The K6 includes six items assessing how frequently one experienced symptoms of psychological distress (e.g., feeling so sad that nothing can cheer you up) during the past 30 days. Items are scored on a five-point scale, from (0) “none of the time” to (4) “all of the time”. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.89 and 0.89 for husbands and wives, respectively. Psychological distress was defined as a dichotomized variable with the cut-off point at a score of 4/523).

3) Social underminingSocial undermining was measured with seven items from the scale of Abbey et al.26). Respondents were asked to indicate to what extent their partner “acted in an unpleasant or angry manner towards you” and so on. Items are scored on a five-point scale, from (1) “not at all” to (5) “a great deal”. Cronbach's alpha was 0.86 and 0.84 for husbands and wives, respectively. Social undermining was defined as having a score above the 33 percentile.

4) Other variablesGender, age, occupation, job contract, working hours, and number of children were included as possible confounders.

Data analysesFirst, demographic characteristics were compared between genders (Table 1). The means, standard deviations and correlations between the key variables were calculated by gender (Table 2). Next, the matched responses of both partners were analyzed with logistic regression analysis to examine whether there were differences among the four work-family conflict groups in terms of psychological distress (Table 3), social undermining reported by partners (Table 4) and partner's psychological distress (Table 5). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. The no conflict group was used as the reference group. PASW Statistics 18 was used for the statistical analysis.

| Men | Women | Statistical test | p value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | Mean | (SD) | n | (%) | Mean | (SD) | |||

| Age (years) | 895 | 38.0 | (5.3) | 895 | 36.1 | (4.3) | t (894)=13.821) | <0.001 | ||

| Occupation | χ2 (16)=380.97 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Worker for private company | 644 | (72.0) | 531 | (59.3) | ||||||

| Civil servant | 78 | (8.7) | 104 | (11.6) | ||||||

| Self-employed | 111 | (12.4) | 89 | (9.9) | ||||||

| Teacher | 17 | (1.9) | 20 | (2.2) | ||||||

| Others | 45 | (5.0) | 151 | (16.9) | ||||||

| Job contract | χ2 (4)=8.69 | 0.069 | ||||||||

| Full time (≥40 hours/week) | 867 | (96.9) | 624 | (69.7) | ||||||

| Part time (<40 hours/week) | 6 | (0.7) | 223 | (24.9) | ||||||

| Others | 22 | (2.5) | 48 | (5.4) | ||||||

| Education | ||||||||||

| High school or below | 261 | (29.2) | 207 | (23.1) | χ2 (4)=185.60 | <0.001 | ||||

| Junior college | 24 | (2.7) | 174 | (19.4) | ||||||

| College or above | 610 | (68.2) | 514 | (57.4) | ||||||

| Working hours / week | 49.6 | (12.3) | 37.1 | (7.7) | t (894)=25.041) | <0.001 | ||||

1) Paired t-test.

| Measures | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Husbands WFC | 7.9 | 4.6 | |||||||

| 2 | Husbands FWC | 1.4 | 1.9 | 0.39 *** | ||||||

| 3 | Husbands psychological distress | 9.2 | 4.1 | 0.37 *** | 0.41 *** | |||||

| 4 | Husbands social undermining (rated by wives) | 14.7 | 5.3 | 0.13 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.18 *** | ||||

| 5 | Wives WFC | 6.6 | 4.5 | 0.09 ** | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.10 ** | |||

| 6 | Wives FWC | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.07 * | 0.17 *** | 0.04 | 0.26 *** | 0.28 *** | ||

| 7 | Wives psychological distress | 9.1 | 4.1 | 0.09 ** | 0.14 *** | 0.08 * | 0.33 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.37 *** | |

| 8 | Wives social undermining (rated by husbands) | 16.0 | 5.4 | 0.24 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.06 | 0.14 *** | 0.13 *** |

WFC=work-to-family conflict; FWC=family-to-work conflict. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001.

| Psychological distress of husbands | Psychological distress of wives | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | OR | (95% CI) | Prevalence (%) | OR | (95% CI) | ||

| No conflict (husbands) n=323 | 12.4 | 1.00 | No conflict (wives) n=327 | 9.2 | 1.00 | ||

| WFC (husbands) n=136 | 28.3 | 2.79 | (1.68-4.66) ** | WFC (wives) n=202 | 30.7 | 4.55 | (2.77-7.47) ** |

| FWC (husbands) n=190 | 23.2 | 2.13 | (1.32-3.42) ** | FWC (wives) n=146 | 23.3 | 3.13 | (1.82-5.38) ** |

| Both conflicts (husbands) n=246 | 53.7 | 8.25 | (5.39-12.63) ** | Both conflicts (wives) n=220 | 49.5 | 10.29 | (6.42-16.50) ** |

WFC=work-to-family conflict; FWC=family-to-work conflict.

no conflict, low for both WFC and FWC; WFC, high for WFC but low for FWC; FWC, low for WFC but high for FWC; and both conflicts, high for both WFC and FWC. The model is adjusted for age, occupation, job contract, working hours and number of children. ** p<0.01.

| Social undermining towards wives by husbands (rated by wives) | Social undermining towards husbands by wives (rated by husbands) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | OR | (95% CI) | Prevalence (%) | OR | (95% CI) | ||

| No conflict (husbands) n=323 | 20.7 | 1.00 | No conflict (wives) n=327 | 25.1 | 1.00 | ||

| WFC (husbands) n=136 | 21.3 | 1.04 | (0.63-1.71) | WFC (wives) n=202 | 28.7 | 1.30 | (0.87-1.95) |

| FWC (husbands) n=190 | 30.0 | 1.64 | (1.09-2.49) * | FWC (wives) n=146 | 39.7 | 2.00 | (1.31-3.04) ** |

| Both conflicts (husbands) n=246 | 39.8 | 2.54 | (1.73-3.72) ** | Both conflicts (wives) n=220 | 40.9 | 2.20 | (1.51-3.20) ** |

WFC=work-to-family conflict; FWC=family-to-work conflict.

no conflict, low for both WFC and FWC; WFC, high for WFC but low for FWC; FWC, low for WFC but high for FWC; and both conflicts, high for both WFC and FWC. The model is adjusted for age, occupation, job contract, working hours and number of children. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01.

| Psychological distress of wives | Psychological distress of husbands | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | OR | (95% CI) | Prevalence (%) | OR | (95% CI) | ||

| No conflict (husbands) n=323 | 21.7 | 1.00 | No conflict (wives) n=327 | 25.4 | 1.00 | ||

| WFC (husbands) n=136 | 23.5 | 1.13 | (0.70-1.85) | WFC (wives) n=202 | 26.7 | 1.05 | (0.70-1.59) |

| FWC (husbands) n=190 | 29.5 | 1.52 | (1.01-2.30) * | FWC (wives) n=146 | 32.2 | 1.38 | (0.89-2.12) |

| Both conflicts (husbands) n=246 | 31.3 | 1.68 | (1.14-2.48) ** | Both conflicts (wives) n=220 | 32.3 | 1.37 | (0.99-1.06) |

WFC=work-to-family conflict; FWC=family-to-work conflict.

no conflict, low for both WFC and FWC; WFC, high for WFC but low for FWC; FWC, low for WFC but high for FWC; and both conflicts, high for both WFC and FWC. The model is adjusted for age, occupation, job contract, working hours and number of children. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics by gender. The husbands were older than the wives. There were also significant differences between husbands and wives concerning occupation, education and working hours. Regarding occupation, more husbands worked in the private sector (72.0%) than wives (59.3%). Regarding education, more husbands graduated from college or above (68.2%) than wives (57.4%). Regarding working hours, husbands worked significantly more hours per week than wives. Regarding job contract (although marginally significant), more husbands worked as a full-time worker (96.9%) than wives (69.7%). Regarding the number of children (not shown in Table 1), 411 couples (45.9%) had one child, 389 (43.5%) had two children, and the remaining 95 (10.6%) had more than three children.

Descriptive statisticsThe means, standard deviations and correlations between the key variables are displayed in Table 2. Among husbands, both WFC and FWC were positively correlated with their own psychological distress, social undermining rated by wives, and psychological distress of wives. In addition, WFC and FWC were positively correlated with each other. Among wives, WFC was positively correlated only with their own psychological distress, whereas FWC was positively correlated with their own psychological distress and social undermining rated by husbands. In addition, WFC and FWC were positively correlated with each other. For both genders, social undermining rated by their partners was positively correlated with psychological distress of their partners as well as with their own WFC and FWC.

Logistic analysesTable 3 shows the associations of one's work-family conflict with one's own psychological distress for husbands (left column) and for wives (right column), respectively. In line with Hypothesis 1, compared with the no conflict group, the both conflicts group was most likely to report psychological distress for both genders. Specifically, for husbands, the both conflicts group had the highest odds ratio for own psychological distress (OR=8.25), followed by the WFC group (OR=2.79) and the FWC group (OR=2.13) after adjusting for demographic variables. For wives, the both conflicts group had the highest odds ratio (OR=10.29), followed by the WFC group (OR=4.55) and the FWC group (OR=3.13).

Table 4 shows the associations (1) of husbands' work-family conflict with social undermining towards their wives (reported by wives: left column) and (2) of wives' work-family conflict with social undermining towards their husbands (reported by husbands: right column). In line with Hypothesis 2, compared with the no conflict group, the both conflicts group was most likely to exhibit social undermining towards their partner for both genders. Specifically, for husbands, the both conflicts group had the highest odds ratio for social undermining towards their wives (OR=2.54), followed by the FWC group (OR=1.64) after adjusting for demographic variables. For wives, the both conflicts group had the highest odds ratio (OR=2.20), followed by the FWC group (OR=2.00), for social undermining towards their husbands.

Table 5 shows the associations (1) of husbands' work-family conflict with their wives' psychological distress (left column) and (2) of wives' work-family conflict with their husbands' psychological distress (right column). In line with Hypothesis 3, for husbands, the both conflicts group had the highest odds ratio (OR=1.68) for wives' psychological distress followed by the FWC group (OR=1.52) after adjusting for demographic variables, although the difference in ORs was not very large. However, for wives, none of the groups had significant odds ratios for husband's psychological distress.

The present study among Japanese dual-earner couples examined the independent and combined associations of WFC and FWC with psychological health of employees and their partners and relationship quality between partners. To our knowledge, this is one of the largest community-based studies that incorporated partner dyads. In what follows, we will discuss the most important contributions of the present study.

Work-family conflict and psychological health (Hypothesis 1)The results of logistic regression analyses clearly supported Hypothesis 1, suggesting that dual experiences of WFC and FWC are more likely to lead to psychological distress compared with sole experience of WFC or FWC. Since dual experiences of WFC and FWC are considered to deplete individuals' resources and provide less opportunity for recovery from resource loss according to COR theory13), employees facing both types of conflict simultaneously are more likely to experience psychological distress.

Although we did not propose a specific hypothesis for this finding, we found that WFC, compared with FWC, was more strongly and adversely related to psychological health of our participants. This result is in line with previous studies whose participants were parents of preschool children27, 28). Since parents with younger children need to invest more resources (e.g., time and energy) in family-related responsibilities such as child care29), interference of work with family is more likely to impair psychological health because parents may feel frustrated and guilty about neglecting their family roles. This speculation can be supported by the evidence that FWC, compared with WFC, was more strongly and adversely related to psychological health when data were collected in broader samples in which participation was not limited to parents of preschool children1, 30-33). Since workers with older children or those without children can invest more resources in work-related responsibilities, the interference of family with work is more likely to impair their psychological health because they feel frustrated about neglecting their work roles.

Work-family conflict and relationship quality between partners (Hypothesis 2)The results of logistic analyses revealed that dual experiences of WFC and FWC were more strongly related to social undermining behaviors towards wives (husbands) compared with the sole experience of WFC or FWC. Although the psychological distress of husbands (wives) could be related to their rating of social undermining because of a negativity bias or because of conflict arising due to the psychological distress, dual experiences of WFC and FWC in husbands (wives) were still significantly related to their social undermining rated by their wives (husbands). This finding supports Hypothesis 2 and is also in line with COR theory13), because partners facing both types of conflict are more likely to feel that their resources, like time and energy, are threatened or lost. According to COR, this makes individuals psychologically distressed, and as a consequence, they are more likely to be hostile and irritable in their interactions with their partner (i.e., undermining behaviors).

Interestingly, FWC was more strongly related to social undermining than WFC was, whereas WFC was more strongly related to psychological distress than FWC was for both genders. This finding may be explained by differences in attributions of responsibility for the cause of both types of conflicts. Our participants may have attributed responsibility for FWC externally to the demands and problems imposed by their partner. More specifically, they may hold their partner responsible for the occurrence of FWC, which then resulted in undermining behavior toward their partner. In contrast, they may have attributed responsibility internally for WFC. Work demands that spill over into the family may have been viewed as resulting from their own inability to effectively manage their work responsibilities. This internal attribution of responsibility for WFC may have resulted in blaming themselves and feeling guilty. Such differences in attributions of responsibility may explain the different pattern in the relationship between WFC and FWC on one hand and social undermining and psychological distress on the other. Future studies should put these hypotheses directly to the test.

Work-family conflict and partner's psychological health (Hypothesis 3)Perhaps the most important theoretical contribution of this study is that it demonstrates the interindividual influences of work-family conflict (i.e., crossover effect) by using both members of the couple as sources of information, although we focused on couples with preschool children. We found that wives whose husbands experienced both WFC and FWC simultaneously were most likely to experience psychological distress. Although we did not examine the detailed mechanisms, the dual experiences of WFC and FWC in husbands and their consequent psychological distress may have led to social undermining towards their wives, which resulted in psychological distress in the wives. This speculation is supported by positive correlations between psychological distress of husbands and social undermining towards wives (r=0.18, p<0.001) and between social undermining towards wives and psychological distress of wives (r=0.33, p<0.001) (see Table 2).

It is important to note that a crossover effect was found only from husbands to wives: crossover was not found from wives to husbands. This suggests that psychological health of wives is influenced by the work-family balance of their partner (i.e., husbands) and their own work-family balance, whereas psychological health of husbands is not influenced by the work-family balance of their partner (i.e., wives). These results contradict previous studies that found bidirectional crossover effects in Western countries7, 34) and even in Japan17). This discrepancy can be explained by the characteristics of (especially female) the participants in the present study. The working hours of our female respondents (37.1 hours/week) were longer than the average working hours of Japanese working women with preschool children (18.5 hours/week)35) and those in the study of Shimazu et al. (35 hours/week)17). Given that our female respondents believed that they should play the main role in childcare and housework, they may feel guilty when husbands experience work-family conflict (mainly FWC) due to increased household responsibilities among husbands. In contrast, husbands may not feel guilty even when wives experience work-family conflict (mainly FWC), probably because husbands think that wives should play the main role in childcare and household work. In sum, the traditional gender role perspective may have led to differences in causal attribution for a partner's work-family conflict, which may have resulted in different associations with psychological distress between genders.

Strengths and limitationsThe present study has several strengths and limitations. With regard to the strengths, first, this study examined the combined associations of WFC and FWC with psychological health and marital interaction—not just the separate association of WFC or FWC. Given the increasing participation of women in the workforce5) and the increasing number of dual-earner couples35), future work-family balance research may benefit from examining the combined associations of both types of conflict. Second, this study was conducted among Japanese dual-earner couples with preschool children, and our findings on spillover and crossover expand previous findings, especially those in Western countries7, 34, 36), because Japan is known as a country whose workforce has significant difficulty balancing their work and family lives. Third, the present study included a relatively large sample, resulting in sufficient statistical power. Also, our participants were working in a wide range of occupational sectors, suggesting that the findings can be generalized across occupations.

In terms of limitations, it should be noted that this study is based on survey data with self-report measures. Aside from self-report bias due to, for example, negative affect, common method variance may also have played a role. Therefore, the true associations between variables might be weaker than the relationships observed in this study. However, a special feature of our study is that—in addition to examining the association of work-family conflict with one's own psychological distress—we examined the association with the relationship quality (i.e., social undermining) reported by the partner and with psychological distress of partners as well, with reduced self-report bias. A second possible limitation is that we used a cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inferences. This means that the relationships proposed by our hypotheses require further testing in longitudinal research. A third possible limitation is that the low response rate may have had unexpected influences on results. There is a possibility that the couples that invested long hours in work and child rearing could not find time to respond to the questionnaire. It is also conceivable that persons who were less interested in work-family issues did not participate in this survey because they did not feel a need to do so. Considering that the working hours of our respondents were longer than the average working hours of Japanese working parents with preschool children35), the latter reason seems more probable. Thus, the true associations between variables might be weaker than the relationships observed in this study. Future research should make an effort to improve the interest in work-family issues among potential participants to reduce this selection bias. A fourth possible limitation is that our respondents were all Japanese dual-earner couples with preschool children, who were characterized by (1) living in a big city (i.e., metropolitan Tokyo); (2) living in an area with a high socioeconomic status22), as illustrated by the fact that the proportion of those whose educational attainment was above college in this study (68.2% for men and 57.4% for women, respectively) was larger than the average proportion in Japanese workers (36.6% for men and 13.1% for women, respectively)37); and (3) long working hours especially among wives. In addition, this study focused on couples with preschool children, and there were no findings about workers with older children and those without children. These characteristics may limit the generalizability of the current findings not only around the globe but also in Japan. Thus, further research is needed to determine whether we can generalize these findings to other areas and other (Western) countries.

In conclusion, dual experiences of WFC and FWC had stronger associations with psychological distress of employees and social undermining towards their partner for both genders. This study also clarified that dual experiences in husbands had a stronger association with psychological distress of their partner (i.e., wives), whereas this was not the case for wives. Future research is needed to clarify the process of how one's dual experience of WFC and FWC affects one's own and one's partner's psychological health and relationship quality between partners.