2016 Volume 58 Issue 3 Pages 247-254

2016 Volume 58 Issue 3 Pages 247-254

Objectives: Our prospective study aimed to elucidate the effect of long-term experience of nonstandard employment status on the incidence of depression in elderly population using the Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA) study. Methods: This study used the first- to fourth-wave cohorts of KLoSA. After the exclusion of the unemployed and participants who experienced a change in employment status during the follow-up periods, we analyzed a total of 1,817 participants. Employment contracts were assessed by self-reported questions:standard or nonstandard employment. The short form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) served as the outcome measure. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate the association between standard/nonstandard employees and development of depression. Results: The mean age of the participants was 53.90 (±7.21) years. We observed that nonstandard employment significantly increased the risk of depression. Compared with standard employees, nonstandard employees had a 1.5-fold elevated risk for depression after adjusting for age, gender, CES-D score at baseline, household income, occupation category, current marital status, number of living siblings, perceived health status, and chronic diseases [HR=1.461, 95% CI= (1.184, 1.805) ]. Moreover, regardless of other individual characteristics, the elevated risk of depression was observed among all kinds of nonstandard workers, such as temporary and day workers, full-time and part-time workers, and directly employed and dispatched labor. Conclusions: The 6-year follow-up study revealed that long-term experience of nonstandard employment status increased the risk of depression in elderly population in Korea.

The growing burden of depression is a serious social problem and one of the most common illnesses in high-income countries1). The prevalence of depression significantly increases with age2), and is consequently high in latest life. A pooled analysis using 24 qualified studies reported that the prevalence in latest life was almost 7% for major depression and 17% for depressive disorder3). In addition, depression can increase other risk factors4) including Alzheimer's, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease5-7).

Depression affects not only the quality of life but also persistent work productivity. More than 50% of the social cost burden of depression results from decreased work productivity8). Depression also acts as a barrier to labor force participation9). Mental illness aggravates departure from the workplace and can expedite the early retirement of elderly workers10). A well-designed prospective study from Europe11) reported that workers with depression retired 2 years earlier than workers without depression. These results are a warning for the urgent social problems experienced by aging workers. Even if workers do not retire, absenteeism or presenteeism due to depression may decrease persistent work productivity. The results of a study from the USA reported that almost 4 hours per week can be lost because of depression-related behavior12). Furthermore, the depressed mood of a worker who has close relationships with co-workers may affect the job strain in co-workers as well13).

There are well-known risk factors for depression in elderly people: physical factors include chronic diseases, chronic pain, and disability; social factors include family and financial changes; and psychosocial factors include difficulty in adapting to such changes14). However, occupational factors related to depression in the elderly population have not been as frequently studied as other risk factors. A well-designed meta-analysis highlighted low job satisfaction as a risk for mental illness15). In addition, another study reported almost 2-4 times greater risk of depression related to economically inadequate job16). Job insecurity increased the risk of depression and anxiety by more than three times, even after controlling for the level of job strain, in Australia17). A study from Korea reported that nonstandard workers were at risk of mental disorder; however, the study design was cross sectional18). Another prospective study shows that employment status change to nonstandard employment increased the risk of depression19). However, there has been little quantitative analysis of the effect of long-term experience of nonstandard employment on depression among elderly workers. Our research aims to elucidate the relationship between the long-term experience of nonstandard employment and the incidence of depression in the elderly population.

Nonstandard employment can be defined as paid employment situations other than those involving full-time and permanent duration, including temporary, day, part-time, and dispatched employment, among others20). The concept of nonstandard work is complex. For example, some full-time workers combine temporary and day work. Some temporary workers are directly employed or dispatched20). Some researchers have suggested that not all nonstandard employments imply a lower quality job status because certain temporary workers can control their time more freely21). However, there is a lack of investigation into the relationship between the risk of depression and various types of nonstandard work separated by their characteristics. Therefore, we have attempted to separate nonstandard employment into meaningful categories to estimate the resulting incidence of depression.

Our prospective study used data from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA) to examine differences in the incidence of depression between standard and nonstandard employees in the elderly population. Because KLoSA included individuals from the elderly working population, analyzing these data may offer valuable scientific knowledge that will help to protect the elderly population from depression. We also examined whether various characteristics of nonstandard employment modify the relationship between employment status and depression.

In this study we used a sample derived from the first- to fourth-wave cohort datasets of KLoSA conducted by the Korea Labour Institute (Seoul) and the Korea Employment Institute Information Service (Seoul). The surveys were conducted in 2006, 2008, 2010, and 2012. The original KLoSA study population comprised South Korean adults, aged 45 years or older, who resided in one of 15 large administrative areas. In 2006, 15 major cities and provinces were selected using stratification, and 10,000 households were randomly selected from these populations. Successful interviews were performed in 6,171 of the 10,000 selected households. A total of 10,254 participants were surveyed. These participants were followed up on a biennial basis until 2012.

Participants were interviewed using the Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing method using Blaise®, a software system developed by Statistics Netherlands that was designed for use in official statistics (http://www.blaise.com/onlinehelp). The interviewers instructed participants to read the questions and input their answers without assistance. The first set of interviews was conducted from August through December 2006, the second set from July through November 2008, the third set from October through December 2010, and the fourth set from July through December 2012. The second survey in 2008 followed up with 8,688 participants, who represented 86.9% of the original panel; the third survey in 2010 included 7,920 participants (77.2% of the original panel); and the fourth survey in 2012 included 7,486 participants (73.0% of the original panel).

KLoSA is a national public database that includes an identification number for each participant (available at: http://www.kli.re.kr/klosa/en/about/introduce.jsp). However, the number is not associated with any personal identifying information. The data collection system and database were designed to protect participant confidentiality. Interviewers provided information about the study objective, methods, potential risks and benefits, and mode of compensation, and informed consent was procured from all participants prior to their participation. The participants also agreed to participate in further scientific research.

We employed the following inclusion/exclusion criteria: (1) during the first phase, only paid workers (n=1,875) were selected from the total sample size (N=10,254), and (2) 58 participants who experienced a change in employment status across the follow-up periods were excluded. A total of 1,817 participants were evaluated for eligibility after applying these inclusion/exclusion criteria. The analytic sample size in the Cox regression model was 1,130 after eliminating candidates with depression at wave (n=685).

Study variables and measurementsEmployment contracts were assessed using questions about employment status and classified into one of two main categories: standard employment or nonstandard employment (which includes temporary, day-labor, part-time, or dispatched employment).

The short form of the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) served as the outcome measure. The CES-D is a brief screening instrument that assesses depressive symptoms experienced during the most recent week. The 10 items are divided as follows: two items that are positively phrased (feel pretty good and generally satisfied) and eight items that are negatively phrased (loss of interest, trouble concentrating, feeling depressed, feeling tired or low in energy, feeling afraid, trouble falling asleep, feeling alone, and hard to get going). The responses for each item range from zero to three. Zero signified very rarely or less than once a day, one signified sometimes or 1-2 days during the past week, two signified often or 3-4 days during the past week, and three signified almost always or 5-7 days during the past week. The summed scores of the 10 items, with scores reversed for the positively phrased items, serve as the outcome variable. Higher scores indicate greater distress. The cut-off between moderately severe and severe depression has been identified as 10 points22). Therefore, in this study we used the standard cut-off score of 10 to categorize individuals with depression.

The incidence of depression was defined as not having depression at baseline and being subsequently identified as depressed at one of the three follow-ups. The follow-up period was calculated as the difference between the date of the first survey and the date of the survey that identified depression. We organized the participants in ascending order of the time of follow-up. If a subject had more than one depressive event during the study period, we chose the first event for the calculation of the follow-up period. If undiagnosed participants were lost to follow-up from the second to fourth set of interviews, their follow-up period was calculated as the difference between the date of the first survey and the date of the final survey that they completed. For the rest of the participants who did not experience a depressive event or were not lost to follow-up, the follow-up period was calculated as the difference between the date of the first survey and the last date of the fourth survey.

The KLoSA survey included questions about a wide array of characteristics. We used age, gender, household income level, and occupation categories as covariates. Income level among individuals in the study population was stratified into quartiles on the basis of annual household income rank, with the first quartile representing the lowest level. Occupation was categorized into six groups: managers and professionals; office workers; service and sales workers; agriculture, forestry, and fisheries workers; craft and machine operators and assembly workers; and manual workers.

Statistical analysesWe first compared the descriptive characteristics between standard employees and nonstandard employees. We calculated the frequencies of the baseline characteristics of participants and compared them to each categorized variable for analysis. We calculated the means [±corresponding standard deviations (SDs) ] of CES-D10 scores and proportions of depression in standard and nonstandard employees at each wave. Hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated using Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate the association between standard/nonstandard employees and the risk of depression. We employed three models: Model 1 (crude), Model 2 (adjusted for age and gender), and Model 3 (adjusted for age, gender, CES-D score at baseline, household income, occupation category, current marital status, number of living siblings, perceived health status, and chronic diseases). Two approaches were used to assess the validity of the proportional hazards assumption. First, we examined the graphs of the log-minus-log-survival functions and found that the plot had parallel lines. Second, we used a time-dependent covariate to confirm proportionality and found that the time-dependent covariate was not statistically significant (p-value=0.4409), suggesting that the hazard is reasonably constant over time. Given that the results could be modified by specific employment type among nonstandard employees, we also performed separate analyses on the subgroups: temporary/day labor, full-time job/part-time job, directly employed/dispatched labor. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (Version 9.22, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) statistical software. A two-tailed p-value of <.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

The mean age (and corresponding SD) of the participants was 53.90 (±7.21) years, and 65.71% were male. Approximately 30% of the study population worked as nonstandard employees, and half of them were manual workers. Nonstandard employment contracts were more frequent among the elderly, females, low earners, and blue-collar workers. The remaining descriptive characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| Standard | Non-standard | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age | ||||||

| <55 | 832 | 66.14 | 275 | 49.19 | 1107 | 60.92 |

| 55-64 | 337 | 26.79 | 182 | 32.56 | 519 | 28.56 |

| ≥65 | 89 | 7.07 | 102 | 18.25 | 191 | 10.51 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 900 | 71.54 | 294 | 56.59 | 1194 | 65.71 |

| Female | 358 | 28.46 | 265 | 47.41 | 623 | 34.29 |

| Household income | ||||||

| 1st quartile (lowest) | 254 | 20.19 | 196 | 35.06 | 450 | 24.77 |

| 2nd quartile | 276 | 21.94 | 214 | 38.28 | 490 | 26.97 |

| 3rd quartile | 310 | 24.64 | 92 | 22.89 | 402 | 22.12 |

| 4th quartile (highest) | 418 | 33.23 | 57 | 10.2 | 475 | 26.14 |

| Occupation (missing=11) | ||||||

| Managers and professionals | 365 | 29.25 | 25 | 4.48 | 390 | 21.59 |

| Office workers | 139 | 11.14 | 24 | 4.3 | 163 | 9.03 |

| Service and sales workers | 132 | 10.58 | 96 | 17.2 | 228 | 12.62 |

| Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries workers | 8 | 0.64 | 24 | 4.3 | 32 | 1.77 |

| Craft, device machine operators, and assembly workers | 302 | 24.2 | 114 | 20.43 | 416 | 23.03 |

| Manual workers | 302 | 24.2 | 275 | 49.28 | 577 | 31.95 |

| Total | 1258 | 69.24 | 559 | 30.76 | 1817 | |

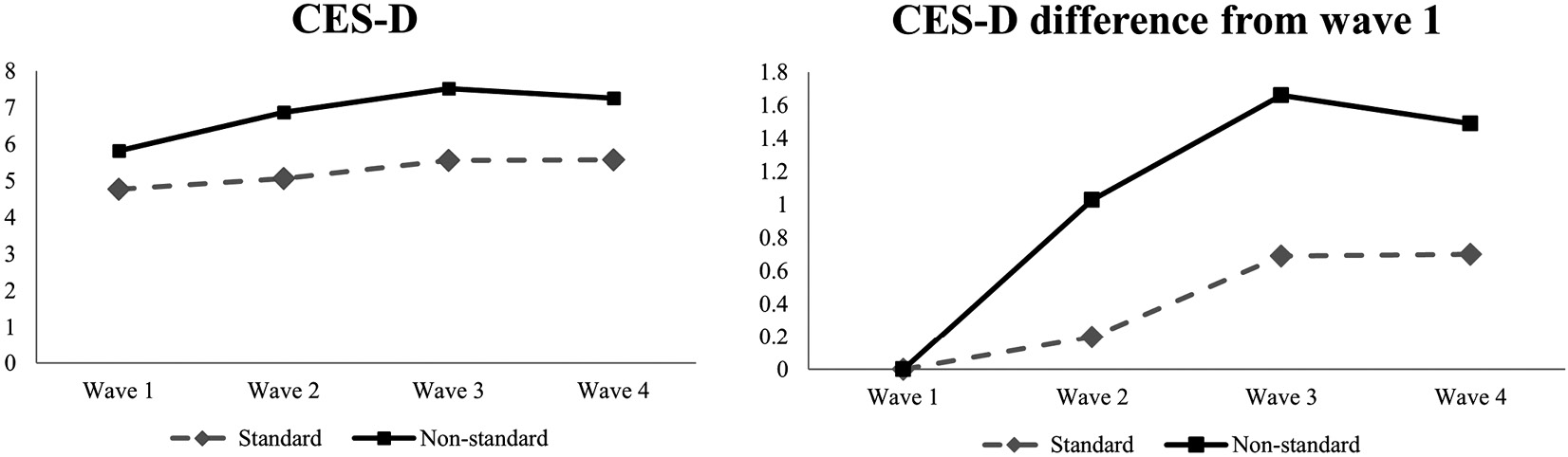

Table 2 shows the CES-D10 scores and the prevalence of depression by employment contract across the follow-up period. Mean CES-D10 scores increased with the follow-up period among both standard and nonstandard employees; however, the difference from wave 1 was greater among nonstandard employees. The mean CES-D10 score differences in each individual from wave 1 to wave 4 were 0.70 (±4.93) and 1.49 (±5.78) among standard and nonstandard employees, respectively (see also Fig. 1). Likewise, the prevalence of depression identified using a cut-off score of 10 also increased with follow-up period, and its increase was greater among nonstandard employees than standard employees; the prevalence of depression increased 6.67% among standard employees, whereas it increased 17.09% among nonstandard employees.

| Standard | Non-standard | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean ± SD | Depression case* (%) | N | Mean ± SD | Depression case* (%) | |||

| *Identified as depression, measured using CES-D of 10 or higher score. | ||||||||

| CES-D | Wave 1 | 1258 | 4.77 ± 3.66 | 113 (8.98) | 552 | 5.82 ± 4.61 | 79 (14.13) | |

| Wave 2 | 1040 | 5.07 ± 4.33 | 141 (13.56) | 476 | 6.88 ± 5.10 | 123 (25.84) | ||

| Wave 3 | 940 | 5.56 ± 4.38 | 158 (16.81) | 427 | 7.52 ± 5.28 | 130 (30.44) | ||

| Wave 4 | 869 | 5.58 ± 4.29 | 136 (15.65) | 394 | 7.26 ± 5.14 | 123 (31.22) | ||

CES-D 10 scores and their differences across the follow-up time points.

We next examined the effect of employment status on the risk of incident depression. Crude and adjusted HRs (with associated 95% CIs) were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards model and the standard employee group as a reference (Table 3). We observed that nonstandard employment significantly increased the risk of developing depression during the 6-year follow-up period. Compared with standard employees, nonstandard employees had a 1.46-fold elevated risk for depression after adjusting for age, gender, CES-D score at baseline, household income level, and occupation category [HR=1.461, 95% CI= (1.184, 1.804) ].

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| total | person-years | case | % | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||||

| Model 1: crude Model 2: adjusted for age and gender Model 3: adjusted for age, gender, CES-D score at baseline, household income, occupation categories, current marital state, number of sibling alive, perceived health status, and chronic diseases The reference group is standard employment, even for all subgroups of nonstandard employment. |

|||||||||||||

| Standard | 788 | 15,030,097 | 221 | 28.05 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | |||

| Nonstandard | 342 | 6,434,610 | 166 | 48.54 | 1.934 | 1.581 | 2.366 | 1.745 | 1.409 | 2.161 | 1.461 | 1.184 | 1.804 |

| Temporary labor | 142 | 2,665,039 | 75 | 52.82 | 2.15 | 1.654 | 2.795 | 1.931 | 1.464 | 2.546 | 1.640 | 1.254 | 2.144 |

| Day labor | 200 | 3,769,571 | 91 | 45.5 | 1.785 | 1.398 | 2.279 | 1.626 | 1.264 | 2.092 | 1.341 | 1.044 | 1.722 |

| Full time | 221 | 4,160,378 | 109 | 49.32 | 1.951 | 1.551 | 2.455 | 1.756 | 1.383 | 2.229 | 1.521 | 1.202 | 1.923 |

| Part time | 121 | 2,274,232 | 57 | 47.11 | 1.899 | 1.419 | 2.542 | 1.724 | 1.273 | 2.335 | 1.357 | 1.010 | 1.821 |

| Directly employed | 271 | 5,106,566 | 128 | 48.23 | 1.855 | 1.492 | 2.306 | 1.681 | 1.335 | 2.117 | 1.406 | 1.121 | 1.762 |

| Dispatched labor | 71 | 1,328,044 | 38 | 53.52 | 2.254 | 1.597 | 3.181 | 1.989 | 1.4 | 2.825 | 1.678 | 1.196 | 2.353 |

The results of separate analyses by employment type among nonstandard employees revealed that the risk of depression was slightly higher among temporary workers than among day workers. However, the other results of the separate analyses did not show any significant differences (i.e., between full-time and part-time jobs or between directly employed and dispatched labor).

In the present prospective study of the elderly population, the risk of incident depression was 1.5 times higher in nonstandard workers than in standard workers. Nonstandard workers were at a high risk of depression, regardless of whether they had a temporary, part-time, or dispatched employment contract. The serious relationship between nonstandard employment characteristics and the risk of depression was still significant even after controlling for age, gender, household income, occupation category, current marital status, number of living siblings, perceived health status, and chronic diseases.

Previously, a cross-sectional study in Korea showed that nonstandard workers are more likely to suffer from mental disorders18), a finding that highlights the need for prospective studies to ensure the existence of such an association. A prospective study in Korea then demonstrated that changes in employment status from standard to nonstandard increased the risk of a new onset of depression in Korean workers19). However, the results of that study do not show that the long-term experience of nonstandard work compared with standard work is related to an increased risk of depression. This result differs from those of our study in which the long-term experience of nonstandard employment is associated with the risk of a new onset of depression. This difference in results may be due to aging because participants older than 55 comprised 15.2% of the participants in the previous study but comprised 39.1% of the participants in our study. Our results suggest that the long-term experience of nonstandard employment is more closely related to depression in older age groups. In Japan, during a 4-year follow-up period, there was a more than two times greater risk of serious psychological distress due to long-term experience of nonstandard employment23). Although the cultural and labor market structures differ between Japan and Korea24), that finding supports our present results.

Nonstandard employment has generally been characterized by job insecurity, an irregular schedule, less required skill, and lower wages. Among these characteristics of nonstandard employment, insecurity is the most important factor in the association between nonstandard employment and risk of depression. The difference between temporary workers and permanent workers may simply be duration. For example, the average income level did not differ between temporary workers and permanent workers in the USA25). The time-limited duration of temporary work is related to job insecurity, and "involuntary" temporary workers are often unsatisfied with their job compared with permanent workers26). Our present results that temporary workers were at risk of depression even after controlling for household income are supported by these findings.

General family and social activities occur during the day and on weekdays. An irregular schedule can disrupt the quality of life via one's relationship with family and social activities27). Personal duties within the family such as childcare, housework, shopping, or banking activities are difficult as part of an irregular work schedule compared with a standard schedule. Furthermore, sleep disturbance may be more common in irregularly scheduled workers28). Sleep disorders are linked to medical as well as socioeconomic consequences28). In demand-control or effort-reward models, nonstandard employees can be categorized into lower-control or lower-reward groups. Long-term nonstandard employment is stressful for workers. Therefore, the general characteristics of nonstandard work disrupt the normal family and social lifestyle. Being employed as a nonstandard worker increases the risk of depression, as our study shows.

As discussed above, the daily pattern of nonstandard work can disrupt one's lifestyle including sleep, family, and social relationships. Such serious links between the daily pattern of nonstandard work and workers' lifestyle could be suggested as causal factors in the development of depression. However, there were no significant differences in depression for temporary vs. day labor, full-time vs. part-time employment, directly employed vs. dispatched labor, or daytime vs. nighttime employment among nonstandard workers (all p-values for these differences were above.05, data not shown in Table 3). This result suggests that specific employment status has a more crucial impact on incident depression than work pattern.

One of the important issues in our study is the bidirectional causality between mental illness and job insecurity. In other words, nonstandard employment can lead to depression while mental illness can lead to job insecurity11,29). To elucidate the causal relationship between mental illness and nonstandard employment, more prospective studies are required. There have been some prospective studies in Europe21). An almost 17-year follow-up panel study found that even permanent workers with mental illness tended to fall into temporary employment status30). In contrary to this causal direction, a recent study from Finnish followed up one hundred thousand public sector workers and found that temporary employment status is a risk factor for mental illness and work disability31). Thus far, however, there have been relatively few prospective studies regarding mental illness and nonstandard employment in Asia. A longitudinal study in Japan23)added to our scientific knowledge of the relationship between nonstandard employment and mental illness; however, more evidence is required. A study from Korea32)performed a comprehensive analysis controlling for sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics; however, the cross-sectional study design limited a clear understanding of the implications for an Asian population. A longitudinal study in Korea investigated only whether a change in employment status affected the incidence of depression19). They did not investigate any association between the long-term experience of a nonstandard worker and risk of depression. Therefore, our prospective study design using a Korean population can help to construct our scientific knowledge regarding the relationship between nonstandard employment and mental illness in Asian populations.

Depression increases the economic burden because of costs of illness, absenteeism, presenteeism, disability, early retirement, and unemployment. Depression decreases productivity and performance during work33). However, depression is a manageable illness compared to other mental disorders34). A systematic review of the literature revealed that increased productivity gains due to treatment for depression could make up for the direct costs of clinical treatment35). Early detection and prevention in the subclinical stages of depression can improve workers' health and workplace productivity34). The diagnosis or detection of early stages of depression in the elderly is often delayed or ignored, although effectiveness of treatment for the elderly is similar to that for younger populations14). Social concern is needed to find and prevent early stages of depression, particularly in elderly nonstandard workers.

There are several limitations in interpreting our present results. A change in employment status is a strong risk factor for depression, and depression can lead to early retirement or unemployment. The exact employment status of our missing population is an important factor to discuss along with our results. The number of follow-up losses was 320 (24.79%) in the standard employment group and 135 (23.12%) in the nonstandard employment group (Supplementary Table 1). The relatively large proportion of follow-up losses should be considered when interpreting our results. Our prospective study design enhanced conclusions about a causal relationship between employment status and risk of depression; however, undetected mental illness can also affect the incidence of depression according to employment status. We excluded workers who had a score of 10 or more on the CES-D10 in wave 1; therefore, we believe that our exclusion criteria guards against this particular limitation. However, it should be noted as a limitation that a single time-point baseline evaluation may not be sufficient to eliminate a possible reverse causation because depressive symptoms may fluctuate, and those who are free from depressive symptoms at baseline may still have had a history of depression, which has affected their work status. Depression is also related to familial history of mental illness; however, we have no medical data of family history. Particular job characteristics such as facing customers and time pressure during work and violence in the workplace are other important risk factors for depression;36) however, we did not have any information about these risk factors. Aging itself is the most important risk factor for depression. We controlled for age in our Cox proportional hazards model, and that adjustment did not attenuate the relationship between incident depression and employment status. Moreover, we controlled for age-related risk factors such as current marital status, number of living siblings, perceived health status, and chronic diseases. However, it is difficult to conclude that all risk factors including aging-related factors were controlled in the current study. Therefore, a more comprehensive study that includes potential risk factors for depression is needed to further elucidate the relationship between incident depression and long-term nonstandard employment status in the elderly population.

In conclusion, the long-term experience of nonstandard employment increased the risk of depression among an elderly population in our 6-year follow-up longitudinal study. All kinds of nonstandard workers (such as temporary and day workers, full-time and part-time workers, or directly employed and dispatched labor) were at risk of depression. Moreover, this serious relationship was statistically significant even after controlling for age, gender, CES-D score at baseline, household income, occupation category, current marital status, number of living siblings, perceived health status, and chronic diseases.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional, and other relationships, that may lead to bias or a conflict of interest. The authors did not received funding from any institutes for this study.