2025 年 26 巻 1 号 p. 31-40

2025 年 26 巻 1 号 p. 31-40

This research has developed a multi-functional food printer that significantly enhances conventional food production technology. The new 3D food printer employs a quad-screw nozzle system and offers three advanced printing methods: duplicator, multi-color and dual-mixing print. In particular, the mixing print technology has shown that it is possible to customize food products according to individual swallowing ability by combining two different hardnesses of material based on the microbially derived polysaccharide, curdlan. Food ink was prepared with 4.3 wt% and 3.6 wt% curdlan concentrations and tested using five different mixing ratios: (i) 0.00:1.00, (ii) 0.25:0.75, (iii) 0.50:0.50, (iv) 0.75:0.25, and (v) 1.00:0.00. The rupture strength tests demonstrated that the maximum stress increased with the 4.3 wt% curdlan concentration, yielding results of (i) 2.0 × 105, (ii) 2.2 × 105, (iii) 2.5 × 105, (iv) 4.1 × 105, and (v) 4.8 × 105 [N/m2]. These findings confirm that the system allows precise control over texture through mixing ratios, supporting the creation of meals that meet individual swallowing needs. Furthermore, this technology enables gradation printing, which not only naturally changes the color of the food but also provides different textures depending on the part being consumed.

現代社会における高齢化の進展に伴い,嚥下障害は高齢者ケアの重要な課題となっている.嚥下障害をもつ高齢者には,柔らかく,しっとりとした飲み込みやすい食品の開発が求められている.しかし,現行の嚥下障害食の多くはマッシュ状またはピューレ状であり,その外見が乏しく,食欲をそそらないため,栄養失調のリスクが増大する可能性がある.さらに,介護食を食べる人々には嚥下能力に個人差があり,全員が同じ硬さや食感の食品を必要とするわけではない.このため,各個人の嚥下能力に応じて食品をパーソナライズ化することが重要である.

本研究では,カードランという微生物由来の多糖類を使用した2種類の材料を用い,3Dフードプリンターの混合造形技術を活用して,硬さが異なる食品を作成した.具体的には,材料の混合比率を調整することで,介護食の分類の中でも5つの異なる硬さの食品を造形し,同一の食品内で硬さが場所によって異なるグラデーション造形を行った.この作成法により,食べる部位によって異なる食感を楽しめる食品を作成し,嚥下障害者の個別のニーズにより細かく対応することを目指した.

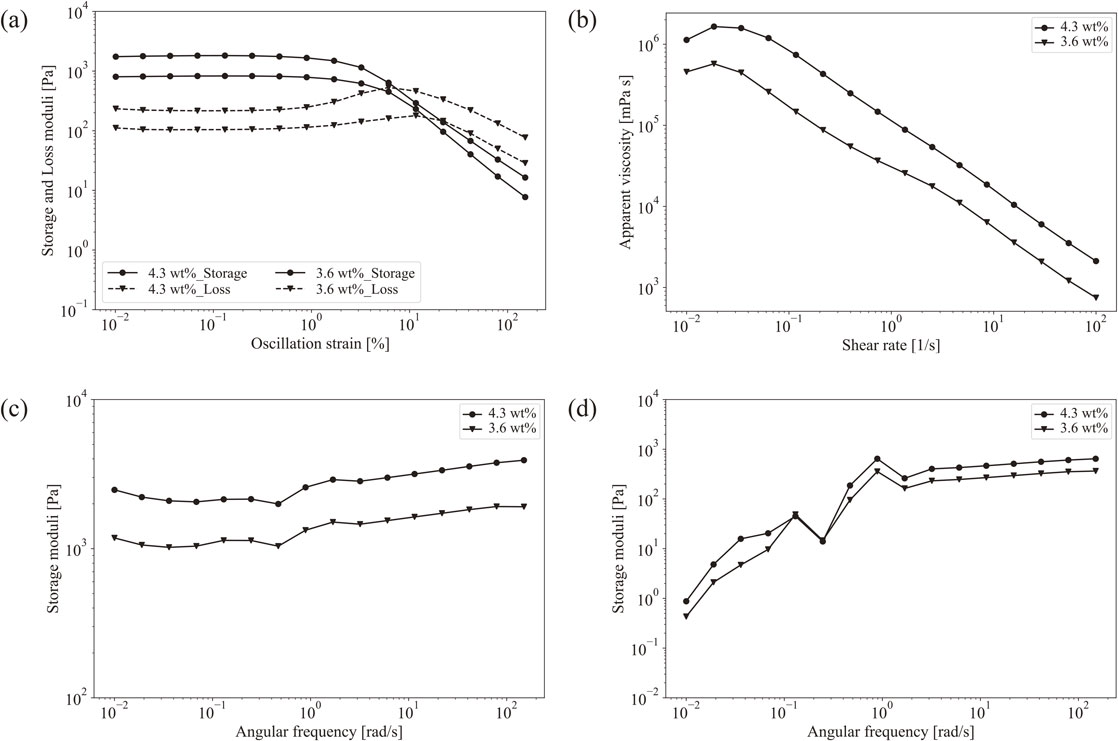

粘弾性特性の評価では,線形粘弾性領域(LVR)により,2つのインクの線形限界が1%未満であった(Fig. 2(a)).LVR内では,ひずみが小さすぎてインクの物理的構造に影響を与えない.この線形領域では,ひずみは材料の物理的構造に影響を与えることがないほど小さく,貯蔵弾性率は損失弾性率よりも高くなった.しかし,LVRを越えると,材料の変形により貯蔵弾性率と損失弾性率の大幅な減少が引き起こされた.損失弾性率が貯蔵弾性率を上回る場合,フードインクは弾性的な力よりも粘性的な力が支配的になり,液体的な挙動を示した.また,3.6 wt%のインクは4.3 wt%のインクに比べて粘度が低く,相対的に動的構造を示した(Fig. 2(b), Table 3).4.3 wt%のインクは,より固体のような挙動を示し,形状保持能力が高い一方で,エネルギーの散逸が多く,せん断変形に対して粘性が高かった.対照的に,3.6 wt%のインクは,より流動的で形状保持能力が低いことが示された.

テクスチャー試験(TPA)では,3.6 wt%のインクが4.3 wt%のインクよりも応力が低く,低い質量パーセンテージのカードランによって形成されたため,応力の変動が少ないことが示された(Fig. 3(a), Table 3).一方,4.3 wt%のインクは,ネットワークの強化により,硬さの変動が大きく,ひずみに対する硬さの増加が顕著であった.加熱後のサンプルを5つの異なる混合比(①0.00:1.00,②0.25:0.75,③0.50:0.50,④0.75:0.25,⑤1.00:0.00)で造形し,破断試験を行った(Fig. 4).混合比の調整により,応力が変化し,特に4.3 wt%のインクの割合が増加するにつれて応力が増加した(Fig. 3(d)).本研究の手法により,患者の嚥下能力や食事の状況に応じて,食事のテクスチャーを柔軟に調整することが可能であることが示された.

With the aging population today, dysphagia has become an important issue in the care of the elderly. Dysphagia is a condition in which an abnormal delay in the process of swallowing food makes it difficult to move food masses. This disorder may increase the risk of coughing, aspiration pneumonia, and even choking [1,2]. Therefore, to cope with dysphagia, soft, moist, and easy-to-swallow foods must be developed. However, most current dysphagia foods are mashed or pureed, which may increase the risk of malnutrition due to their lackluster appearance and unappetizing nature [3]. To solve this problem, the concept of “universal design food (UDF)” is gaining popularity in Japan. According to the Japan Nursing Food Council, UDF is defined as a processed food with an ingenious shape and physical properties, and voluntary standards based on hardness and viscosity have been established. UDF manufactured according to these standards is not only easier to swallow but also has improved appearance and taste, enhancing nutrition for the elderly. However, although certain standards have been established for nursing food, the wide range of these standards makes it difficult to provide meals that perfectly match individual swallowing abilities. At present, there is not enough detailed support to address the specific needs of each patient. Therefore, it is crucial to personalize foods based on individual swallowing abilities to optimize meals [4-6]. Nonetheless, reconstituted diets often face the challenge of achieving uniform texture, resulting in an anisotropic quality, meaning that the texture remains the same regardless of which part of the diet is consumed [7-9]. This consistency can detract from the overall eating experience, making it crucial to address the textural aspects of UDFs to enhance enjoyment.

3D food printers are innovative technologies that enable precise control over the shape and texture of food products, allowing for personalization according to individual needs [10]. Among traditional 3D printers, the FP-2500 stands out due to its specific features and its screw-based extrusion system. This printer is equipped with two tanks, facilitating both dual-color and single-color printing, although its functionalities are somewhat limited. Research involving the FP-2500 has explored the printing possibilities of pumpkin paste and burdock puree with added protein and gelling agents [11,12]. These studies underscore the potential of 3D food printing to enhance the quality and acceptability of dietary options for individuals with special needs.

Our latest screw 3D food printer integrates three innovative technologies—duplication, multi-color, and mixing—to produce uniquely diverse and creative food products. The screw-based extrusion method significantly enhances the replication capabilities of 3D food printing, improving production efficiency and enabling the rapid mass production of identical food items. For example, the same cookie or candy can be produced in different flavors and colors, providing consumers with a wide array of choices [13,14]. The multi-color printing function allows for cake decoration and the creation of colorful gummies, offering visual appeal and diverse flavors [15,16]. Additionally, by combining materials with varying hardness levels, different textures can be achieved within the same food. For instance, incorporating fruit pieces of varying firmness into fruit jellies or adding a crunchy texture to smoothies is possible. Moreover, for health-conscious foods, different nutritional components can be blended to meet individual health needs. This capability is expected to provide more delicious and visually appealing food products.

Although a variety of food materials (e.g., pork, chicken, fish gelatin, vegetable blends, and edible mushrooms such as black wood ear mushroom and shiitake mushrooms) have been used in previous studies to produce dysphagic foods using 3D printing technology, research on adjusting texture and shape is still insufficiently advanced. However, research on adjusting texture and shape has not progressed sufficiently [17-21]. Hydrocolloids, starches, and other additives are commonly used to achieve the desired texture and consistency and to enhance the functionality of personalized foods [22,23]. The interaction of the added hydrocolloids with key nutrient compounds present in the food may alter the overall structure, texture, rheological properties, and sensory characteristics of the food. In addition, food inks need to be thixotropic, which results in viscoelastic properties that behave like a liquid during extrusion and return to a solid-like structure after deposition in order to maintain print structure and stability [24,25]. Among additives, curdlan are of interest in food processing due to their excellent gelling properties. It has a lower gelatinization temperature than starch, which allows for a more flexible processing temperature. This characteristic enables the formation of complex shapes and adjustments to texture, providing greater versatility in food formulation [26]. This property allows for more precise gelation, improving food quality and texture. The addition of artificial colorants also improves the appearance of food products, making them more attractive to consumers. Therefore, this study will focus on the potential of 3D food printing using a microorganism-derived polysaccharide called curdlan.

In this study, two materials using a microbial polysaccharide called curdlan are used to create foods of different hardness by utilizing the 3D food printer’s mixing and printing function. Specifically, by adjusting the mixing ratio of the materials, food of five different hardnesses can be created. Furthermore, this technology can also be applied to create gradations of different hardness within the same food depending on its location. This makes it possible to create foods with different textures depending on the part of the body that eats them, and to respond more precisely to the individual needs of people with dysphagia. Through this experiment, we aim to realize individualized nursing food and improve the dietary satisfaction and quality of life (QOL) of people with dysphagia. Furthermore, it is expected to significantly increase flexibility and creativity in food processing, with the aim of improving the quality of gradients by mixing ingredients in the right proportions. This approach will not only contribute to improved food quality, but will also facilitate the development of new food production methods to meet the diverse needs of consumers. Hardness refers to the values for food texture that were not directly measured. Maximum stress refers specifically to the measured hardness of the food samples.

Figure illustrates the applications of our developed 3D food printers, showcasing the appearance and axis settings of the newly proposed printer along with an overview of its four main features: (a) Quad, (b) Duplicator, (c) Multi-color, and (d) Mixing. The Quad feature allows for the simultaneous printing of up to four different inks through separate channels, with one nozzle mounted per syringe. The Duplicator technology enables the simultaneous formation of multiple identical food items. Utilizing four independent nozzles, this technology can print up to four identical shapes simultaneously, even with different materials and colors. Additionally, the Multi-color feature allows for the creation of designs using up to four colors. In contrast, the Mixing feature employs a Y-junction nozzle to output ingredients fed from two separate tanks while mixing them within the nozzle. One mixing nozzle can be mounted for every two syringes, meaning that if four syringes are used, two mixing nozzles can be installed to blend materials from separate tanks inside the nozzle. This Y-junction-based configuration is commonly used in microfluidics for mixing, focusing, and emulsifying fluids but has not been widely adopted in the food sector [27-30]. Therefore, it is important to understand the rheological properties of food inks and set the appropriate extrusion pressure to ensure optimal printing performance.

Quad nozzle technology for 3D food printing. (a) Overview, (b) cross-section, (c) design drawings.

The 3D food printer utilised in this study is controlled by a high-performance control board, which ensures fast and stable operation, essential for precise 3D printing tasks. Remote control functions allow the printer to be conveniently managed from a remote location. In addition, a macro set-up pre-extrudes the food ink before printing starts to improve print quality. Real-time monitoring allows users to observe the printing process and make the necessary adjustments for optimum print results.

The G-code command set is essential in controlling the 3D food printer, particularly for managing the extrusion of multiple materials [31]. A virtual extruder setup is implemented in the printer’s firmware, allowing for the simultaneous extrusion of different materials at specified rates. In this context, a virtual extruder refers to a software abstraction that enables the printer to manage multiple material extrusions as if they were physical extruders. The tool represents the actual print head configuration that corresponds to each virtual extruder, while a driver is the hardware component that controls the physical extruder motor. Details of the virtual extruder settings are outlined as follows: the M563 command is utilized to define each tool, specifying the tool number (P) and the associated drivers (D). For example, the combination of drivers 0, 1, 2, and 3 are configured as Tool0. The M563 command is specific to the Duet firmware and is not a standard G-code command; it allows users to define a tool with multiple drivers, facilitating complex multimaterial printing setups. The M567 command is then used to specify the material extrusion rates for each tool; in this setup, extruders E0, E1, E2, and E3 are set to extrude at 100% each. This configuration facilitates precise control of the multimaterial printing process, enhancing the printer’s ability to produce complex food items with varied compositions.

The virtual extruder configurations for E0 and E1 are summarized in the below. The extrusion rate for material dispensed from a single nozzle is set at 100% and adjusted according to specific requirements. Tool7 to 27 are set up for mixing different materials (Table 1). For mixed nozzles, the settings E0:0.1 and E1:0.9 facilitate controlled dispensing of materials. This configuration also applies to E2 and E3, ensuring a consistent approach to material dispensing across multiple extruders.

| Printing mode | Configuration Command |

|---|---|

| Mixing | Mixing materials in varying proportions |

| Tool7 | M567 P7 E0.00:1.00 |

| Tool8 | M567 P8 E0.05:0.95 |

| … | … |

| Tool26 | M567 P26 E0.95:0.05 |

| Tool27 | M567 P27 E1.00:0.00 |

The mass percentages of 3.6 wt% and 4.3 wt% refer to the curdlan content in the food inks. Curdlan is prepared using color gel from Ichimasa Kamaboko Co. (Japan), with a specific colorant added to the 4.3 wt% ink to achieve the desired color. These materials are mixed uniformly using a manual mixer, a critical process to ensure consistent quality in 3D printing. The precise formulation and mixing procedure of the individual ingredients increased the reproducibility of the recipe and enabled the production of an optimized food ink. This approach has resulted in increased precision and flexibility in food processing and the production of high-quality food products with a wide variety of shapes and textures.

2.4 Rheological measurementsRheological measurements of the ink are carried out on an MCR 302 (Anton Paar, Austria) rheometer with parallel plates of 25 mm diameter and 1 mm gap height. All samples are loaded, carefully trimmed, and allowed to rest for 5 minutes before starting measurements. This resting period ensures consistent starting conditions for each test. For the dynamic rheological experiments, a fixed frequency of 1 Hz, a temperature of 25°C, and a strain sweep (0.01-150%) are performed to determine the linear viscoelastic range (LVR). This test helps identify the range within which the material behaves elastically and maintains its structural integrity under deformation. After determining the LVR, a new sample is loaded, and a frequency sweep test (0.01-150 rad/s) is conducted. Additionally, the apparent viscosity is measured over a frequency range of 0.01 to 100 [1/s]. The measurements are performed in the linear viscoelastic region of the ink, and the storage moduli (G’) and loss moduli (G’’) are determined to evaluate the material’s elastic and viscous properties. Each test was conducted three times, and the average value of the measurements was calculated to ensure reliability.

2.5 Texture profile analysis and rupture strength testsIn the evaluation of food inks for 3D printing, understanding their mechanical properties is crucial. A creepmeter (RE2-33005C, Yamaden Co Ltd, Japan) is utilized to measure the stress under specific conditions tailored for food products suitable for nursing care. For the pre-heating evaluation, a 40 mm diameter petri dish is filled with the ink to a height of 15 mm. A 20 mm diameter plunger is used to compress the material at a speed of 10 mm/sec up to a clearance of 5 mm, following standard protocols for evaluating food consistency in healthcare. Post-heating, the evaluation is conducted using a wedge-shaped plunger with dimensions of 1×30 mm, while maintaining the same compression speed, to perform a rupture test on the shaped objects [32]. The test is conducted at a strain rate of 90%. Since it is considered difficult to capture the structural characteristics of the shaped objects with a cylindrical plunger, a V-shaped plunger is used in this study. Each test was conducted three times, and the average value of the measurements was calculated to ensure reliability.

It should be noted that the texture profile analysis (TPA) is compliant with the UDF standards. However, the rupture test in this study does not adhere to these standards due to the use of a V-shaped plunger. This choice was made because it is considered difficult to capture the structural characteristics of the shaped objects with a cylindrical plunger.

2.6 Sample printingSamples are printed using two different types of food ink, each with a different solidity. The samples are printed into 30 mm × 30 mm × 4.8 mm rectangles, with the outline set to 0 and the fill rate set to 100%. Experimental conditions include a nozzle diameter of 1.5 mm, a pitch of 1.2 mm and a print speed of 800 mm/min, and the production time for each printed object is approximately 3 minutes. After 3D printing, the final heating process is carried out using a superheated steam oven (ER-WD7000, Toshiba, Japan) with a low temperature steaming process at 95°C for four minutes. This heating process gelatinize the material and adjust it to the right consistency to be eaten. This stabilizes the physical properties of the product and further improved its texture and quality.

Calibration was first carried out to determine the appropriate dispensing volume of the material. These measurements were made to assess the flow and mechanical properties of the material in detail. The data obtained from the preliminary experiments were integrated into the calibration process in order to determine more accurate dosing rates. The mixing of the material was then controlled by adjusting the rotation ratio of the two motors in order to perform mixing printing.

2.7 Ink mixing ratio and screw rotation controlTo assess the effect of the mixing ratio on the screw speed, we calculated shear rates based on the rotational motion of the screw. Shear rate, denoted as $\dot{\gamma }$, represents the rate of deformation imparted to the fluid, which is essential for understanding fluid behavior under the process conditions. The shear rate $\dot{\gamma }$ for a rotating screw is given by:

| (1) |

where D is the diameter of the screw, N is the rotation speed of the screw (in rpm), and H is the channel depth of the screw. Using Eq. (1) and the maximum rotation speed (Nmax = 13.4rpm), the shear rate under maximum operating conditions was calculated to be 2.51 1/s. The maximum speed is set at 13.4 rpm, and the following five mixing ratios (4.3 wt%: 3.6 wt%) were analyzed: (1) 0.00 : 1.00, (2) 0.25 : 0.75, (3) 0.50 : 0.50, (4) 0.75 : 0.25, and (5) 1.00 : 0.00.

The effect of the mixing ratio φ on each screw’s rotation speed is described by:

| (2) |

where Nmax is the maximum rotation speed and φ represents the proportion of one component in the mixing ratio. This formula indicates that as the proportion of one component (φ) increases, the rotation speed of the corresponding screw decreases while the other screw’s speed increases, as shown in Table 2. By combining Eqs. (1) and (2), we can calculate the shear rates that arise from different mixing ratios, thereby linking the rotation speed adjustments directly to shear rate and the flow behavior of the ink mixture under various conditions.

| Mixing ratio | Screw N1 [rpm] | Screw N2 [rpm] |

|---|---|---|

| 0.00 : 1.00 | 13.4 | 0 |

| 0.25 : 0.75 | 10.05 | 3.35 |

| 0.50 : 0.50 | 6.7 | 6.7 |

| 0.75 : 0.25 | 3.35 | 10.05 |

| 1.00 : 0.00 | 0 | 13.4 |

Following the determination of the linear viscoelastic region (LVR), the dynamic viscoelastic properties are further analyzed (Fig. 2 (a)). A dynamic frequency sweep from 0.01 to 150 rad/s is performed while maintaining the same controlled temperature. This step measured the ink’s response to various oscillation frequencies, helping to clarify the relationship between the ink’s structure and its ability to recover after being subjected to stress [33,34]. Measurements within the LVR showed that all food inks remained intact under less than 1% strain, demonstrating their capacity to withstand minor stresses without permanent deformation. However, above the LVR, the storage elastic moduli (G’) and loss elastic moduli (G’’) were found to decrease significantly. In particular, the point at which the storage moduli falls below the loss moduli indicates that the viscoelastic behaviour of the ink changes from elastic to viscous properties. This change is particularly noticeable in the strain range above about 1.7%, where G’ decreases rapidly and the loss moduli (G’’) becomes dominant, giving the ink liquid-like properties. In 3D printing extruders, the ink is subjected to large shear forces as it passes through the nozzle. It is common for the ink to experience deformation beyond the linear viscoelastic region (LVR) due to these forces. A key point in this process is the transition of the ink behaviour from elastic to viscous. The liquid-like behavior of the ink as it passes through the nozzle allows it to be extruded smoothly, to become more fluid and to be placed more accurately. On the other hand, as the loss moduli decreases and viscosity increases, the printed material becomes more stable and plays an important role in retaining its shape. In particular, the behaviour after about 3.22% strain, when the loss moduli becomes dominant, is important for stable printing in 3D printing, suggesting that the balance between liquid-like behaviour and viscosity of the printed food is favourable for shape retention. [35,36].

Graphical representation of the rheological properties of food inks. (a) Strain sweep showing the linear viscoelastic range, (b) apparent viscosity depicting flow characteristics, (c) storage moduli and (d) loss moduli illustrating the inks’ structural responses to applied frequency. The plotted values represent the average of three measurements.

Apparent viscosity is a key factor in 3D printing because the appropriate level ensures smooth material dispensing and improves modeling accuracy [37,38]. If the viscosity is too low, the layers may not adhere properly, leading to a loss of printing precision. It is also important for the flow curve of the material to show exponential decay, signifying thixotropic properties, which means the material can flow under external shear stress and return to its original state, enabling proper printing. Furthermore, the gelling agent content significantly impacts viscosity in 3D printing. In the current experiments, when the mass percentage of the gelling agent is increased from 3.6 wt% to 4.3 wt%, the apparent viscosity rose significantly (Table 3). Specifically, at low shear rates (from 0.01 to 0.0185 [1/s]), the viscosity increased by a factor of at least 2, which significantly affects material discharge and interlayer adhesion (Fig. 2(b)). Higher viscosities limit material fluidity, resulting in more stable discharge rates and more precise printing. However, excessively high viscosity can also overburden the printer’s nozzle, making dispensing difficult. On the other hand, reducing the gelling agent content lowers the viscosity, making the material too fluid, which compromises interlayer adhesion and the strength and accuracy of the printed object. These findings underscore the importance of selecting the optimal amount of gelling agent to establish suitable 3D printing conditions.

| Samples | Rheological behavior | TPA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viscosity ($\dot{\gamma }$ = 2.51 1/s) [mPa s] | G’ (0.1 %) [Pa] | G’’ (0.1 %) [Pa] | Stress [N/m2] | |

| Curdlan 4.3 wt% | 53928 ± 1003 | 1100 ± 1.0 | 49 ± 0.3 | 552 ± 47 |

| Curdlan 3.6 wt% | 17683 ± 566 | 550 ± 0.7 | 0.83 ± 0.2 | 199 ± 34 |

As internal friction increases, the storage (G’) and loss moduli (G’’) of the ink also increase with rising vibration frequency (Fig. 2(c)). This suggests that the interactions between molecules and particles in the ink intensify, leading to greater viscoelasticity and more pronounced energy storage and dissipation. At higher frequencies, molecular chain and particle interactions become more robust, and the internal dynamic structure stiffens. Comparing samples with 3.6 wt% additive to those with 4.3 wt% additive, the 4.3 wt% sample exhibits significantly higher storage and loss moduli. This difference reflects the stronger internal structure formed by the increased additives and the enhanced intermolecular interactions. Specifically, the rise in G’’ indicates that the 4.3 wt% ink behaves more solid-like and has better shape retention. Conversely, the increase in G’’ suggests more energy dissipation due to internal friction, making the 4.3 wt% ink more viscous to shear deformation. In contrast, the 3.6 wt% ink shows a softer dynamic structure, with smaller increases in storage and loss moduli as vibration frequency increases. This implies that the 3.6 wt% ink is more fluid and has weaker shape retention.

3.2 TPA and rupture strength resting results and gradation printingThe results of TPA tests conducted before heating revealed that the 3.6 wt% food ink, with a lower curdlan mass percentage, had lower firmness than the 4.3 wt% ink (Table 3). This is due to the relatively slow gel network formed by the lower curdlan concentration, which results in less variation in firmness [39]. On the other hand, the higher curdlan concentration of 4.3 wt% led to more significant firmness fluctuations and a pronounced increase in firmness in response to strain, due to network strengthening. This demonstrates the ability to finely tune the material’s physical properties.

Rupture tests were conducted on samples after heating, prepared with a mixing ratio of 4.3 wt%:3.6 wt% in the following five proportions: (i) 0.00:1.00, (ii) 0.25:0.75, (iii) 0.50:0.50, (iv) 0.75:0.25, and (v) 1.00:0.00. Sample (ii), dominated by 3.6 wt% ink, showed a gradual increase in stress under strain and stable material properties (Fig. 3). It also had a firmer texture with higher maximum stress than sample (i), indicating that firmness can be tailored to specific texture and firmness requirements for a patient’s diet. Sample (iii) had medium firmness among the five samples and provided a balanced texture. Sample (iv), dominated by 4.3 wt% ink, showed a significant increase in stress under strain, reflecting a firmer texture. This shows the potential to increase firmness as needed.

(a) Stress of each sample measured by TPA before heating, plotted as strain [%] against stress [N/m2] (b) Stress of each sample determined by the rupture test, also plotted as strain [%] against stress [N/m2]. The shaded gray area at the bottom indicates the range from a ratio of 4.3 wt%: 3.6 wt% = 1.00: 0.00 to a ratio of 4.3 wt%: 3.6 wt% = 0.00: 1.00, demonstrating that all samples fall within this range. (c) Illustration of the rupture testing methodology, indicating the printing direction and cutting direction. The figure also highlights the rupture points observed in gradient-printed samples. (d) Results of rupture tests with error bars for gradient-printed food samples. The plotted values represent the average of three measurements.

These findings indicate that by adjusting the mixing ratio, hardness can be precisely controlled, an important factor in personalizing care food (Fig. 3(d)). By flexibly adjusting texture according to the patient’s preferences and dietary needs, meal satisfaction can be improved, and meals tailored to individual nutritional requirements can be provided. This highlights the importance of textural variety and personalization in care diets and suggests a novel approach to future meal design.

Previous studies have focused on designing the texture of care foods using macroscopic 3D structures with two different materials, primarily leveraging the physical properties and structural elements of these materials to alter texture [12]. In contrast, this research adopts an approach of mixing the same materials in varying ratios. This method allows for precise adjustments of texture and hardness, enabling the flexible design of foods tailored to individual needs. Specifically, by changing the mixing ratios of the materials, a variety of textures can be created, providing foods that align with the desired softness or chewiness required by users. This innovative approach facilitates more precise control over texture, contributing to the enhancement of the quality of care foods and diversifying the overall eating experience. Additionally, gradient printing is performed using mixing ratios from (i) to (v) to achieve varying textures depending on the part of the food being eaten (Fig. 4). This suggests the possibility of enhancing the enjoyment of meals by offering different textures while maintaining the same flavor. The design allows the front part of the food to be softer, gradually hardening toward the back, providing different textural experiences during consumption. This gradient structure could potentially break the monotony of eating and help maintain appetite. However, when using materials with different hardness or viscosities, the harder material tends to be discharged less easily, making it difficult to print according to the intended mixing ratio (Fig. 4c-d). Additionally, since there is a distance between the mixing section and the extrusion section, even when switching to the next mixing ratio, residual material from the previous ratio may still be extruded, resulting in insufficient mixing. This could lead to slight inconsistencies in texture throughout the printed structure, affecting the intended gradient pattern.

3D printing results for different mixing ratios of the two types of food ink. Each sample is printed with a different mixing ratio (4.3 wt% and 3.6 wt% ink) Gradient printing results. A structure with a gradual change in hardness from front to back is formed, with the foremost part being the softest and the hardness increasing towards the rear.

The study utilized a 3D food printer to provide personalized meals for elderly people with swallowing difficulties. In particular, food inks based on the microbially derived polysaccharide curdlan are used to create foods of different hardness to achieve the optimum texture for each individual’s swallowing ability. This technology makes it possible to create gradations of hardness within the same food, which enhances the enjoyment of eating and is expected to further improve the quality of meals. In addition, by stabilizing the physical properties of the food, the texture and quality of the food can be improved, enabling flexible provision of meals according to the needs of individual users. This approach responds to the modern need for a detailed response to individual preferences and swallowing ability in the design of meals for elderly people with dysphagia. Further technological innovations and deeper research into practical applications are expected to improve the quality of life of people with dysphagia in the future. In particular, the diversification of textures by combining different ingredients and hardnesses and the development of further precise gradient printing techniques will make the provision of more diverse and personalized meals a reality. This approach will open up new possibilities in food processing and provide an important basis for a richer diet.

screw diameter, mm

G’storage moduli, Pa

G’’loss moduli, Pa

Hcannel depth, mm

Nscrew rotation speed, rpm

$\dot{\gamma }$shear rate, 1/s

φproportion of one component in the mixing ratio, -