2016 年 39 巻 8 号 p. 1309-1318

2016 年 39 巻 8 号 p. 1309-1318

An adequate immune response to percutaneous vaccine application is generated by delivery of sufficient amounts of antigen to skin and by administration of toxin adjuvants or invasive skin abrasion that leads to an adjuvant effect. Microneedles penetrate the stratum corneum, the outermost layer of the skin, and enable direct delivery of vaccines from the surface into the skin, where immunocompetent dendritic cells are densely distributed. However, whether the application of microneedles to the skin activates antigen-presenting cells (APCs) has not been demonstrated. Here we aimed to demonstrate that microneedles may act as a potent physical adjuvant for successful transcutaneous immunization (TCI). We prepared samples of isolated epidermal and dermal cells and analyzed the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and costimulatory molecules on Langerhans or dermal dendritic cells in the prepared samples using flow cytometry. The expression of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules demonstrated an upward trend in APCs in the skin after the application of 500- and 300-µm microneedles. In addition, in the epidermal cells, application of microneedles induced more effective activation of Langerhans cells than did an invasive tape-stripping (positive control). In conclusion, the use of microneedles is likely to have a positive effect not only as an antigen delivery system but also as a physical technique inducing an adjuvant-like effect for TCI.

Vaccination has been one of the most successful medical manipulations for the prevention of infectious diseases for the last two centuries.1,2) The majority of vaccines are administered by subcutaneous or intramuscular injections. Nevertheless, these administration methods still have the following drawbacks: pain and stress, requirement of trained people for correct application, and needle-related disease owing to reuse of the needle.3)

Transcutaneous immunization (TCI), which is noninvasive and easier to use, has received widespread attention as an alternative method to injection to overcome these problems. The skin consists of three layers: the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. Compared with subcutaneous and muscular tissues, the epidermal and dermal layers of the skin contain a large number of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), including Langerhans cells (LCs) and dermal dendritic cells (dDCs).4,5) Therefore, TCI is expected to enable efficient vaccination with the least amount of antigen.6–8) The stratum corneum, the outermost layer of the epidermis, serves as a barrier that prevents chemicals and exogenous substances from entering the body. As the barrier function interferes with the success of TCI, a number of physical techniques for the enhancement of antigen delivery into the skin have been investigated. These techniques include powder injection,9,10) iontophoresis,11,12) sonophoresis,13,14) patch formulations,15,16) and microneedles.17–19)

In recent years, the use of microneedles has emerged as a novel invasive technique. Microneedles reliably penetrate through the stratum corneum and can create an efficient permeation pathway into the skin and consequently improve the delivery of high-molecular-weight substances including antigens.20–24) Furthermore, microneedles potentially allow self-vaccination in a simple manner without pain.

In previous studies, solid metal microneedles for TCI have been fabricated from titanium or stainless steel coated with an antigen. Zhu et al. reported that in mice, compared with intramuscular injections, the application of stainless steel microneedles coated with influenza vaccine to the skin could elicit a stronger immune response than that of intramuscular injections in mice.17,18) In addition, dissolving microneedles, which are composed of water-soluble chondroitin, dextran, and hyaluronic acid, and dissolve within the skin, were also investigated. Application of the dissolving microneedles composed of chondroitin encapsulated with antigen induced strong antibody responses comparable to those induced by subcutaneous immunization.25) Most studies regarding vaccination with microneedles have described that the strong immune responses elicited by the microneedles were attributed only to the quantitative amount of antigen delivered into the epidermal or dermal layers.

LCs and dDCs in the epidermis and dermis, respectively, have crucial roles in antigen presentation in TCI. Among APCs, LCs are considered to have the highest ability for antigen presentation. Activation of APCs immensely enhances their ability to capture antigen, and thereby elicit an antigen-specific immune response.26–28) Seo et al. studied effective immunization using activated LCs and addressed the augmented expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and costimulatory molecules (CD86, CD80, CD54) on LCs, the enhanced cytokine activity, the increased cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity, and the T cell proliferation. Strong antigen-presenting capacity was obtained in activated LCs isolated from tape-stripped (TS) skin compared with LCs isolated from nonactivated intact skin.29,30) These findings suggest that physical stimulation such as TS of the skin provide a possible beneficial effect for the enhancement of antigen-presenting capacity.

Considering the possible activation of APCs by physical stimuli (TS), there may be two important matters to enhance the effect of TCI as follows: 1) effective delivery of antigens into the epidermis and/or dermis by penetrating the stratum corneum and 2) effective activation of APCs in the epidermis and/or dermis by some kind of physical technique. Microneedles have the potential to provide both effective delivery of antigens and activation of APCs in the skin. However, it has not been demonstrated whether the application of microneedles to the skin can activate APCs in the skin. The purpose of our study was to investigate the effect of physical stimuli induced by microneedles on the activation of LCs and dDCs. Expression of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules (CD86, CD80, CD54) on LCs and dDCs in mouse skin were measured using flow cytometry.

A stamp-type microneedle device, Derma Stamp, was obtained from CA CELEB BEAUTY (Osaka, Japan). FcR Blocking reagent, phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled CD11b, allophycocyanin-labeled MHC class II were obtained from Miltenyi Biotec K.K. (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Allophycocyanin/Cy7-labeled CD45, Brilliant Violet 511-labeled CD11c, PE/Cy7-labeled CD86, Brilliant Violet 421-labeled CD80, and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled CD54 were obtained from Biolegend Co., Ltd. (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). Sodium chondroitin sulfate was from ZPD A/S (Esbjerg, Denmark). Brilliant Green was obtained from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). All other materials used were of reagent grade and were used as received.

AnimalsMale C57BL/6 mice, 7 weeks old, were obtained from the Sankyo Labo Service Corporation, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). Animals were housed for 1 week under a 12-h light and dark cycle in a temperature-controlled room (23±2°C) with free access to food and water. All of the protocols involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Josai University Life Science Centre (Saitama, Japan).

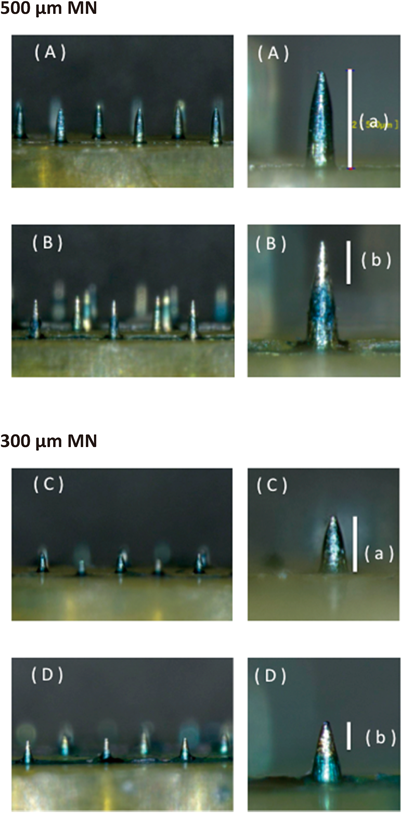

Physicochemical Properties of MicroneedlesFigure 1 shows the overall and magnified views of the stamp-type microneedle device used in the present study. It has 34 microneedles in a circular stand with a diameter of 8 mm. The microneedles were made from titanium. We used two types of microneedles with mean needle lengths of 497.6±0.9 and 298.7±1.4 µm, designated 500- and 300-µm microneedles, respectively (Table 1). The basement diameters of the needles were 179.6±1.8 and 157.6±2.0 µm, respectively.

The microneedles are composed of titanium arranged in a circle of 8 mm radius. The Derma Stamp has 34 microneedles.

| Actual height (µm) | Actual diameter at basement (µm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Five hundreds micrometer microneedles | 497.6±0.9 | 179.6±1.8 |

| Three hundreds micrometer microneedles | 298.7±1.4 | 157.6±2.0 |

Each value shows the mean±S.E. (n=9).

To estimate the insertion depth of the microneedles in mouse skin, the microneedles were coated with a mixture of chondroitin sulfate and Brilliant Green as water-soluble polymer and dye marker, respectively. After 1 mg of Brilliant Green was added to 100 mg sodium chondroitin sulfate, 160 µL of distilled water was added and mixed at room temperature. The resulting mixture was used to coat the microneedles. The coated microneedles were dried using silica gel, and then lengths of the coated portion of the microneedles were measured to estimate the insertion depth of the needles in the skin. The coated portions of the microneedles then dissolve in the interstitial fluid in the skin when applied. The coated microneedles were applied on shaved dorsal skin by pressing, and then the lengths of the dissolved portions of the coated microneedles were measured as the index of the insertion depth.

In Vivo Treatment with Microneedles, TS, and Subcutaneous InjectionMale C57BL/6 mice, 8 weeks old, were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/kg). The hair of the dorsal skin on the right and left sides was removed using an electric shaver and depilatory cream. Each group included eight or more mice. The 500- or 300-µm microneedles were applied on the right side of the shaved dorsal skin (1×2 cm2) by pressing and holding the handle of the device for 10 s. For the TS experiment (positive control),31,32) the stratum corneum barrier was disrupted by stripping three times on the right side of the shaved dorsal skin (1×2 cm2) with Cellotape® (Nichiban, Tokyo, Japan). For the subcutaneous injection experiment, 0.1 mL of saline solution was injected at three different sites of the right dorsal skin. The left side of the shaved dorsal skin was not treated and thus served as a control. At 12 h after treatment, skin samples were excised from the mice. For the study using 500-µm microneedles, skin samples were also obtained at 3, 6, and 24 h after the application to estimate the time dependency of the responses.

Preparation of Isolated Epidermal and Dermal CellsEpidermal cells were isolated from the dorsal skin samples using an epidermal dissociation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Epidermal cell suspensions were prepared by vigorous pipetting and filtered on a 70-µm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, Le Pont de Claix, France). Dermis samples obtained by separation from skin samples were incubated for 1 h in the solution containing hyaluronidase type IV-S (Sigma-Aldrich Japan, Tokyo, Japan) at 2000 U/mL and collagenase type II (Funakoshi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 400 U/mL for isolation of dermal cells. Dermal cell suspensions were prepared by vigorous pipetting and filtered through a 70-µm cell strainer.

Flow CytometryWe prepared epidermal or dermal cell suspensions from skin treated with and without application for assessment of the expression of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules (CD86, CD80, CD54) in epidermal LCs or dermal DCs using flow cytometry. All monoclonal antibodies were used at the recommended amount per 106 cells. Cell suspensions pooled from two mice were incubated with FcR blocking reagent for 10 min to prevent nonspecific binding of the subsequent reagents to Fc receptors. Each group was composed of four to six experiments. Furthermore, epidermal and dermal cells were stained with seven different antibodies, allophycocyanin/Cy7-labeled CD45, PE-labeled CD11b, Brilliant Violet 511-labeled CD11c, allophycocyanin-labeled MHC class II, PE/Cy7-labeled CD86, Brilliant Violet 421-labeled CD80, and FITC-labeled CD54, for 30 min on ice. Fluorescence profiles of epidermal or dermal cells were analyzed in a FACScan with MACS Quant Analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec). Dead cells were detected by propidium iodide uptake. CD45+, CD11b+, and CD11c+ cells, identified as LCs in the epidermis or dDCs in the dermis, were gated to examine CD86, CD80, CD54, and MHC class II expression in LCs and dDCs. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD86, CD80, CD54, or MHC class II on LCs or dDCs was also measured on a log scale. Since the MFI of these molecules on LCs or dDCs varied among experiments, the relative MFI (RMFI) was calculated as RMFI=MFI of treated skin samples (right dorsal skin)/MFI of control skin samples (left dorsal skin).

Observation of Skin Configuration after Application of MicroneedlesThe microneedles were applied to the dorsal skin by pressing and holding the handle of the device for 10 s. After removal of the device, photographic images of the treated skin were recorded using a digital camera (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) at 0, 3, 5, 10, 15, 30, and 60 min.

Statistical AnalysisDescriptive statistics are presented as the mean values±standard error (S.E.). The statistical significance of the difference was calculated by paired t-test for comparisons within the same group and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test or Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons between groups. Differences with p<0.05 considered statistically significant.

Microneedles coated with a mixture of chondroitin sulfate and Brilliant Green were prepared to estimate the insertion depth of microneedles in the skin. When the coated microneedles are applied to the skin, they encounter interstitial fluid and the coating on the inserted portion of the microneedles is dissolved in the skin. Figure 2 shows the micrographs of the coated microneedles before and after the application to mouse skin in vivo. The lengths of the coated portion of the microneedles before the application were roughly the indicated lengths of the needles (500, 300 µm) (Table 2). The observed lengths of the dissolved portions of the microneedles after the application of the 500- and 300-µm microneedles were 230.3±4.9 and 127.7±3.3 µm, respectively (Table 2). These data indicated that the 500- and 300-µm microneedles could penetrate to depths of approximately 230 and 130 µm from the skin surface, respectively.

(A, C) Images of coated microneedles before application. (B, D) Images of coated microneedles after the application on the shaved dorsal skin. The white bars indicate the whole coated portion before application (a) and the dissolved portion after application (b).

| Length of coated portion (µm) | Length of dissolved portion (µm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Five hundreds micrometer microneedles | 494.9±3.5 | 230.3±4.9 |

| Three hundreds micrometer microneedles | 300.4±1.8 | 127.7±3.3 |

Each value shows the mean±S.E. (n=6–11).

The antigen-presenting capacity of dendritic cells such as LCs and dDCs depends on the degree of the expression of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules.33,34) The MFI values of MHC class II, CD86, CD80, and CD54 in LCs in the treated skin were 277.93±20.21, 29.45±0.92, 3.47±0.55, and 16.6±2.60, respectively, at 12 h after treatment. These MFI values were approximately 3.5-, 3.5-, 1.4-, and 1.3-fold higher than those observed in their respective controls without treatment, indicating increased expression of MHC class II, CD86, CD80, and CD54 on the LCs in the skin treated with 500-µm microneedles. In particular, LCs in the treated site expressed significant levels of CD86 and MHC class II molecules, both of which are crucial for antigen presentation (Fig. 3). These results suggest that the application of 500-µm microneedles to the skin induces activation of LCs in the epidermis at 12 h after application.

The treated skin samples were obtained 12 h after application of microneedles. The epidermal cells were stained with allophycocyanin/Cy7-CD45, PE-CD11b, Brilliant Violet 511-CD11c, allophycocyanin-MHC class II, PE/Cy7-CD86, Brilliant Violet 421-CD80, and FITC-CD54 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Gating by CD45+, CD11b+, and CD11c+ was set so that LC-bearing and size-gated epidermal cells were included in the analysis. The MFI of MHC class II, CD86, CD80, and CD54 on LCs in epidermal cells was measured using flow cytometry (B) (MFI; white bar: control, black bar: treated with 500-µm microneedles). Each point shows the mean±S.E. of five experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated by paired t-test. * p<0.05, *** p<0.001: significantly different from control.

The potential time dependency of the expression of immunocompetent molecules was investigated as shown in Fig. 4. Expression of MHC class II and CD86 in LCs was significantly increased at 6 and 12 h after application of the 500-µm microneedles, and then returned to control levels at 24 h. Expression of CD80 at 3, 6, and 12 h and that of CD54 at 3 and 6 h was moderately increased on the LCs. Expression of CD80 and CD54 also returned to control levels at 24 h after the application. These results suggest that LCs in the epidermis are rapidly and transiently activated by the application of 500-µm microneedles.

The RMFI was calculated as MFI of treated skin samples with application of 500-µm microneedles (right dorsal skin)/MFI of control skin samples (left dorsal skin). Epidermal cell suspensions isolated from control skin samples, and treated skin samples with application of 500-µm microneedles were stained with anti-CD45, -CD11b, -CD11c, -MHC class II, -CD86, -CD80, and -CD54 monoclonal antibodies and analyzed using flow cytometry. Gating by CD45+, CD11b+, and CD11c+ was set so that LC-bearing and size-gated epidermal cells were included in the analysis. Each value shows the mean±S.E. of four to five experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated using ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 compared with the RMFI at 0 h.

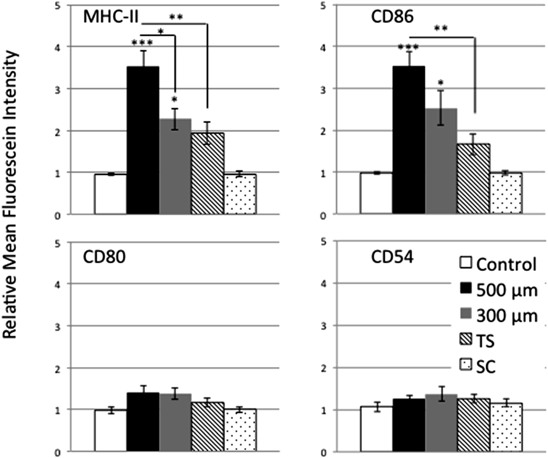

We next focused on the difference in LC activation by various physical treatments, including microneedles, TS, and subcutaneous injection to the skin. Animals were divided into five groups: 500-µm microneedles; 300-µm microneedles; TS (positive control); subcutaneous injection; and no treatment (control). In our separate study, LCs were highly activated at 12 h compared with 6 and 24 h after treatment with TS as reported by Kubo et al.31) On the other hand, the subcutaneous injection did not induce the activation of LCs at 6, 12 and 24 h after treatment (data not shown). Thus, assays using flow cytometry were performed for the epidermal LCs at 12 h after each treatment. TS treatment served as a positive control since acute barrier disruption by TS is known to induce effective activation of LCs.28,29) After TS treatment, the RMFI values for MHC class II, CD86, CD80, and CD54 on LCs were 1.94±0.27, 1.66±0.25, 1.17±0.10, and 1.26±0.10, respectively, and the degree of expression of MHC class II and CD86 tended to be higher than those of the control group. This result was consistent with the findings of Seo et al.29) and Nishijima et al.,30) suggesting the relevance of TS treatment as a positive control. To compare the effect of insertion depth of microneedles on the skin, different needle sizes (500 or 300 µm) were used. The RMFI values for MHC class II, CD86, CD80, and CD54 were 3.52±0.37, 3.52±0.35, 1.41±0.14, and 1.26±0.10, respectively, after application of the 500-µm microneedles and 2.27±0.26, 2.52±0.41, 1.37±0.13, and 1.37±0.17, respectively, after application of the 300-µm microneedles, indicating that application of microneedles to the skin may induce more effective activation of LCs compared with TS treatment. Furthermore, the RMFI values for MHC class II and CD86 tended to be higher after treatment with 500-µm microneedles compared with those after treatment with the 300-µm microneedles. A significant difference was observed in the expression of MHC class II. Thus, the use of 500-µm microneedles might be effective for activation of immune responses in TCI compared with the 300-µm microneedles. On the other hand, the RMFI values for the molecules on LCs after subcutaneous treatment were not different from the control (Fig. 5).

The RMFI was calculated as MFI of treated skin samples (right dorsal skin)/MFI of control skin samples (left dorsal skin). The epidermal cell suspensions were prepared from right and left dorsal skin. The right dorsal skin was treated with microneedles, TS, or subcutaneous injection 12 h previously. The left dorsal skin was not treated. Neither side of the dorsal skin was treated in the control group. Subsequently, these isolated cells were stained with allophycocyanin/Cy7-CD45, PE-CD11b, Brilliant Violet 511-CD11c, allophycocyanin-MHC class II, PE/Cy7-CD86, Brilliant Violet 421-CD80, and FITC-CD54 and analyzed using flow cytometry. Each point shows the mean±S.E. of four to six experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated using ANOVA with Tukey’s test. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001: significantly different from control or 500-µm microneedles group.

We expect that the application of microneedles can affect immune responses of not only LCs in the epidermis but also dDCs in the dermis. Figure 6 shows expression of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules on dDCs after treatment with 500-µm microneedles. Treatment with 500-µm microneedles significantly increased the expression of MHC class II and CD86 compared with control (Fig. 6A). The MFI values for MHC class II, CD86, CD80, and CD54 on dDCs after treatment with 500-µm microneedles were 334.75±37.41, 48.76±2.09, 15.00±0.78, and 18.62±0.67, respectively. On the other hand, the MFI values for MHC class II, CD86, CD80, and CD54 in controls without treatment were 153.21±12.73, 28.65±2.82, 12.45±2.21, and 18.08±1.21 (Fig. 6B), respectively. As higher values were observed in the treated skin, application of microneedles to the skin could induce activation of dDCs in the dermis as well.

Dermal cell suspensions were prepared from skin treated with or without application of 500-µm microneedles. The treated skin samples were obtained at 12 h after this application. The epidermal sheet was removed from the skin samples. Subsequently, the dermal cells were isolated from the residual skin samples. The dermal cells were stained with allophycocyanin/Cy7-CD45, PE-CD11b, Brilliant Violet 511-CD11c, allophycocyanin-MHC class II, PE/Cy7-CD86, Brilliant Violet 421-CD80, and FITC-CD54 and analyzed using flow cytometry. Gating by CD45+, CD11b+, and CD11c+ was set so that dDC-bearing and size-gated dermal cells were included in the analysis. The MFI of MHC class II, CD86, CD80, and CD54 on dDC in dermal cells was measured using flow cytometry (B) (MFI; white bar: control, black bar: treated with 500-µm microneedles). Each point shows the mean±S.E. of five experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated by paired t-test. ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001: significantly different from control.

Differences in dDC activation by various means of stimulating the skin were assessed. Animals were divided into four groups: 500-µm microneedles; 300-µm microneedles; subcutaneous injection; and no treatment (control). The RMFI values for MHC class II, CD86, CD80, and CD54 on dDCs in the control group were 1.02±0.09, 1.05±0.03, 1.01±0.04, and 1.01±0.02, respectively. The RMFI values for the molecules on dDCs after treatment with 500-µm microneedles were 2.20±0.21, 1.74±0.10, 1.32±0.19, and 1.04±0.06, and after 300 µm were 1.87±0.13, 1.55±0.12, 1.14±0.19, and 1.07±0.07, respectively. As shown in Fig. 7, significant increases in the RMFI values of MHC class II and CD86 were observed in both 500- and 300-µm microneedles groups compared with the control group. On the other hand, treatment with subcutaneous injection did not increase the RMFI values of the molecules on dDCs. These results suggest that treatment with microneedles induces activation of immune responses of dDCs, whereas subcutaneous injection, the most common method of vaccination, does not significantly induce dDC activation.

The RMFI was calculated as MFI of treated skin samples (right dorsal skin)/MFI of control skin samples (left dorsal skin). The dermal cell suspensions were prepared from right and left dorsal skin. The right dorsal skin was treated with microneedles or subcutaneous injection 12 h previously. The left dorsal skin was not treated. Neither side of the dorsal skin was treated in the control group. Subsequently, these samples were stained with allophycocyanin/Cy7-CD45, PE-CD11b, Brilliant Violet 511-CD11c, allophycocyanin-MHC class II, PE/Cy7-CD86, Brilliant Violet 421-CD80, and FITC-CD54 and analyzed using flow cytometry. Each point shows the mean±S.E. of four to five experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated using ANOVA with Tukey’s test. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01: significantly different from control group.

Figure 8 shows photographic images of mouse skin after the application of 500- and 300-µm microneedles. Obvious traces impressed by microneedles were observed immediately after application at the applied site. The traces disappeared within 1 h, although the traces impressed by 500- and 300-µm microneedles remained for 15 and 5 min, respectively. Obvious indications of potential inflammation or damage do not appear to be evident on the applied sites of the skin.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the effect of physical stimuli induced by microneedles on the activation of LCs in the epidermis and dDCs in the dermis. Our results showed that physical stimuli of the skin by the application of microneedles have the ability to activate LCs and dDCs in addition to directly delivering antigens into the skin, as reported in a previous study.25) It is expected that application of microneedles to the skin induces a potent adjuvant-like effect in TCI.

The skin also has a role as an immunological barrier as well as a penetration barrier that protects the body against exogenous compounds, including antigens. The outermost layer of the epidermis is the stratum corneum, which is 10–15 µm thick and is a strong primary barrier against exogenous compounds, such as drugs. The viable epidermis (100–150 µm thick) underlying the stratum corneum is a living cell layer containing keratinocytes and LCs.35) Keratinocytes account for approximately 90% of the total epidermal cell population and play an important role in innate immunity in the skin. When the body is exposed to danger, they produce many cytokines, chemokines, and antimicrobial peptides as basic signal transducers. LCs account for approximately 1–3% of the total epidermal cell population. Although LCs constitute a low proportion of the cells in viable epidermis, they occupy 25% of the total skin surface area36) and are crucial for antigen presentation in immune responses. On the other hand, the cell population in the dermis is composed of fibroblasts, dendritic cells, and mast cells. Dendritic cells, one of APCs, are also important in immune responses in the skin, in addition to LCs in the epidermis. Because skin has a large number of professional APCs including LCs and dDCs compared with other tissues, the skin has been considered as an ideal target tissue for vaccine delivery.

In this study, we elucidated that APCs in skin were affected by physical stimuli applied by microneedles. Two different needle sizes (500, 300 µm) in microneedle devices were used in this study to evaluate the effect of penetration depth of the needles on APCs in the skin. We chose these needle sizes because the usefulness of these microneedles are commonly investigated.17,19,37) Microneedles having a needle length of 500 µm were likely to be more effective than 300-µm microneedles in terms of activation of MHC class II on LCs (Fig. 5). Similarly, dDCs tended to be activated by application of both 500- and 300-µm microneedles, although a significant difference in activation was not observed between the two needle sizes (Fig. 7). Application of 500-µm microneedles seemed to be much more effective for LC activation than for dDC activation. Based on these results, activations of LCs and dDCs are likely to depend on the insertion depth of microneedles; that is, the 500-µm microneedles can reach near the middle portion of dermal tissue over viable epidermis, whereas the 300-µm microneedles can reach the upper portion of dermis. Neither 500- nor 300-µm microneedles can go through the dermis and the difference of the insertion depth between two microneedles is ca. 100 µm (Table 2). Taking into consideration of the dermal layer’s thickness in mice (about 400 µm), the difference of the insertion depth of 100 µm may not be definitive for dDCs activation in dermis. This is likely to be involved in our observation of no significant difference in dDCs activation, although the activation by 500-µm microneedles tended to be higher than that by 300-µm microneedles. Since our present study is first study showing the potential activation of dDCs by the physical stimuli such as microneedles, further investigation will be required to ascertain the effect of the physical stimuli including microneedles for the dDCs as well as LCs. There were few activated LCs in the skin at 24 h after the application of microneedles (Fig. 4). In our separate study, we observed by a whole-mount immunostaining technique using the epidermal sheet that the immunostaining of MHC class-II on the LCs in the epidermal sheet were attenuated at 24 h after application of microneedles compared with that at 12 h (data not shown). In addition, MHC class II-positive cells lost a considerable fraction of dendrites and showed a round shape. Tokura et al. demonstrated that epidermal LCs activated by TS treatment migrated to the peripheral draining lymph nodes at 24–48 h after treatment.30) Thus, this may explain the observed decrease in MHC class II staining at 24 h in our study demonstrated after TS treatment. Further studies will be required to clarify such time-dependent depression of LC activation.

Furthermore, Ito et al. reported that 40- and 70-kDa FITC-labeled dextran administered intradermally by self-dissolving micropile were found in the skin over 24 h after administration,38) indicating that high-molecular-weight substances remain in the epidermis and/or dermis for a long time after intradermal administration. Vaccine antigens are peptides, in general, which commonly have a high molecular weight. Therefore, vaccine antigens have the potential to remain in the skin for a few hours after administration by a TCI system, although possible degradation of antigen should be taken into consideration. In our time course study, the activation of LCs was increased at 3 h after application of microneedles (Fig. 4). LCs and dDCs activated by physical stimuli of microneedles may continue to capture the remaining antigens in the skin. Therefore, capability of LCs and dDCs for capturing antigens is likely to be a concern with respect to the results of our time course study.

It is well known that initiation of acquired immunity requires antigen presentation by MHC class II and costimulatory signals induced by activation of innate immunity.30,39) That is, innate immune activation involving a costimulatory signal is essential and important for subsequent acquired immunity. The best-characterized T cell/APC interactions at the molecular level include CD4/MHC class II, CD28/B7 (CD86, CD80), and LFA-a/CD54. We focused on MHC class II, CD86, CD80, and CD54 in the present study.40–43) CD86 may be most important among costimulatory molecules. Nishijima et al. reported that T cell proliferation was inhibited almost completely by anti-CD86 monoclonal antibody, whereas suppression by anti-CD54 monoclonal antibody was partial. Furthermore, T cells were activated even in the presence of anti-CD54 monoclonal antibody.30,44) In our study, LCs in the skin at 12 h after application of microneedles expressed high levels of MHC class II and CD86 and moderate levels of CD80 and CD54 (Fig. 3). Similarly, expression of MHC class II and CD86 on the dDCs was increased by the application of microneedles, although the increased expression on dDCs was less than that on LCs (Fig. 6). Thus, physical stimuli by the microneedles can activate LCs and dDCs effectively in TCI.

Immunological adjuvants are often coadministered with vaccines to enhance the immune response to the target antigen. One of the adjuvants roles is to activate the innate immune system. As a result, costimulatory molecules on APCs can be induced. It can be expected that the adjuvants stimulate APCs, trigger the antigen presentation, and increase the adaptive immune responses. Recently, it was demonstrated that the activation of innate immunity by some adjuvant is essential for vaccination.39) Application of microneedles to the skin in the present study clearly indicated the induction of LC and dDC activation with increasing MHC class II and costimulatory molecules, suggesting that physical stimuli by the microneedles function as an adjuvant-like action to enhance immune responses in the skin. Indeed, Sullivan et al. and Kim et al. reported that administration of influenza vaccine using microneedles could elicit stronger immune responses than those of intramuscular injections in mice without adjuvant substances.45,46) Moreover, it is important to ensure the safety of vaccine adjuvant in addition to vaccine efficacy after administration. Recently, it has been reported that some adjuvant substances provoked critical adverse effects.47,48) Adjuvant-like effect by the microneedles, on the other hand, may be advantageous from the point of view of safety, since they are generally prepared from biocompatible materials.

Activation of LCs and dDCs induced by physical stimuli by the microneedles is likely to be maximized within a range of several hours (ca. 12 h) as shown in the present study; meanwhile, traces on the skin impressed by the microneedles had disappeared within 1 h (Fig. 8). This may imply that biological events continuing after stimulation by the microneedles are responsible for the time difference in APC activation. Several studies demonstrated that keratinocytes in the viable epidermis produced various cytokines that were released into the surrounding environment when skin was exposed to physical stimuli associated with barrier disruption.44,49–51) Therefore, physical stimuli to the skin may induce the release of immune cytokines from living cells such as keratinocytes and sustainably affect the activation of LCs and dDCs in an indirect manner.

In summary, we demonstrate in the present study that application of microneedles can induce an adjuvant-like effect on the activation of APCs in skin. Because the microneedles deliver antigens directly into skin, this technique is expected to be applied in the development of TCI systems. In recent years, investigation of vaccine development has broadened to include various diseases such as infectious disease, cancer, neural disease, and allergic disease.52–54) Our findings in the present study provide an incentive to explore the potency of physical techniques for transdermal drug delivery, such as microneedles.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.