2019 Volume 67 Issue 5 Pages 476-480

2019 Volume 67 Issue 5 Pages 476-480

Surugamides are a group of non-ribosomal peptides isolated from marine-derived Streptomyces. Surugamide A (1) and its closely related derivatives, surugamides B–E (2–5), are D-amino acid containing cyclic octapeptides with cathepsin B inhibitory activity. The D-isoleucine (Ile), the nonproteinogenic amino acid residue embedded in 1, is less common in natural peptides because a rare Cβ-epimerization is required for its biosynthesis. Taking advantage of the synthetic route of 2 previously established by our group, we synthesized the cyclic octapeptide 1 containing D-Ile by solid phase peptide synthesis. The structure of 1 actually contains D-allo-Ile in place of D-Ile, which was corroborated by chemical syntheses and chromatographic comparisons.

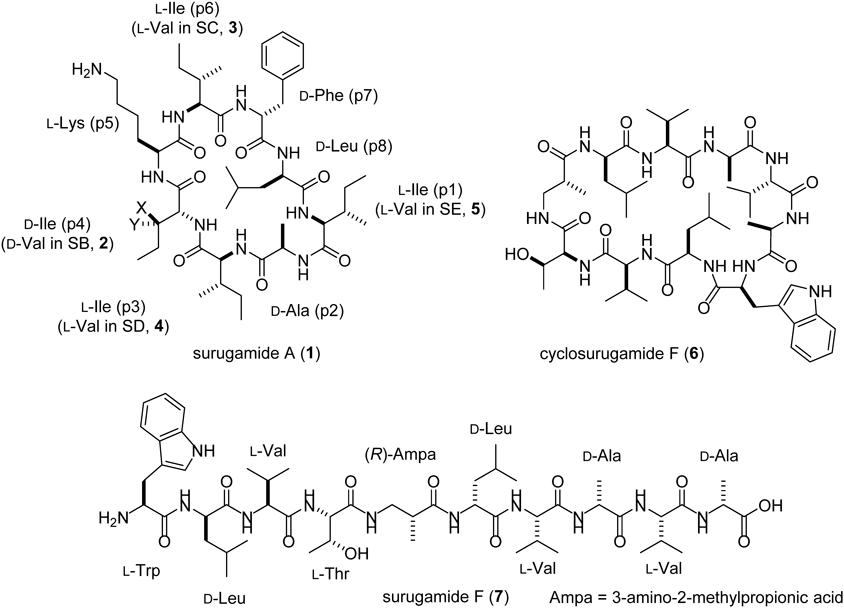

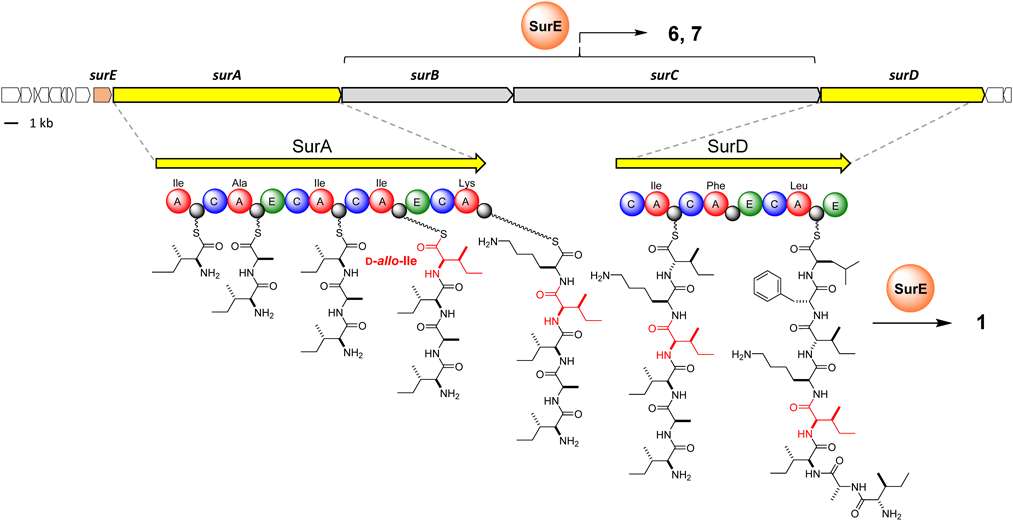

Surugamides, two groups of structurally unrelated non-ribosomal peptides (NRP), are produced by marine actinomycetes, Streptomyces sp. JAMM992 and several other Streptomyces strains.1–4) Surugamide A (Fig. 1, 1), a cyclic octapeptide with cathepsin B inhibitory activity was identified in 2013, along with the structurally related derivatives surugamides B–E1) (Fig. 1, 2–5). Its biosynthetic gene cluster consists of four NRPS genes, surA–D5) (Fig. 2). The two NRPS genes, surA/surD, which are responsible for the synthesis of the cyclic octapeptides are separated by two additional NRPS genes, surB/surC, responsible for the synthesis of cyclosurugamide F (Fig. 1, 6), a structurally unrelated cyclic decapeptide, and its linear derivative, surugamide F5,6) (Fig. 1, 7). Both peptide assembly lines lack the canonical thioesterase (TEs) domains that generally catalyze the offloading and macrocyclization of the grown peptides.7) Instead, SurE, a penicillin-binding protein that is physically discrete from the mega-synthetase, acts in trans with both assembly lines to release the cyclooctapeptides (1–5) and the cyclodecapeptide (6), respectively, highlighting their unique biosynthetic systems4) (Fig. 2).

1a (proposed structure): X = Me, Y = H, 1b (revised structure): X = H, Y = Me “p” in structure of surugamide A stands for “position.”

The NRPS genes surA/surD for syntheses of 1–5, surB/surC for syntheses of 6, 7, and the trans-acting thioesterase SurE are colored in yellow, gray, and orange, respectively. The colored balls represent functional domains: blue, condensation domain; red, adenylation domain; gray, peptidyl-carrier protein; green, epimerization domain; orange, trans-acting thioesterase SurE. (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

Another feature of the octapeptidic surugamides is the D-isoleucine (Ile) residue present at the position 4 in 1 and 3–5 (Fig. 1, 2 is a derivative with D-Val at the position 4). D-Ile is an enantiomer of L-Ile with the epimerization at the two stereogenic centers at the Cα-, and Cβ-positions. The epimerization at the Cα-position commonly observed in NRP is generally proceeds via two ways: the direct activation of the D-amino acid by the D-amino acid-specific adenylation (A) domain, or the equilibration of the Cα configuration of the PCP-tethered biosynthetic intermediate catalyzed by the epimerization (E) domain.8) In the case of surugamide biosynthesis, whereas the epimerization of the Cα-position of the Ile residue at the position 4 (Ile-4) should be facilitated by the E domain in module 4 of SurA, the biosynthetic mechanism for the epimerization at its Cβ-position is obscure. The epimerization at the Cβ-position is relatively rare in nature and, to the best of our knowledge, only one type of biosynthetic machinery has been identified for L-allo-Ile biosynthesis in the desotamides9) and marformycin10) pathways. In the biosynthesis of L-allo-Ile, pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent aminotransferases (DsaD and MfnO in the biosyntheses of desotamide and marformycin, respectively) and the cognate isomerases (DsaE and MfnH in the biosyntheses of desotamide and marformycin, respectively) cooperate to convert L-Ile to L-allo-Ile.11) However, a pair of homologous enzymes is not encoded in the biosynthetic gene cluster of the surugamides. In this study, we first synthesized D-Ile-containing 1 by taking advantage of the established route for the total synthesis of 2.4) This led us to realize that 1 actually does not possess D-Ile; therefore, the reported structures of the cyclic octapeptide surugamides 1, 3–5 need to be corrected.

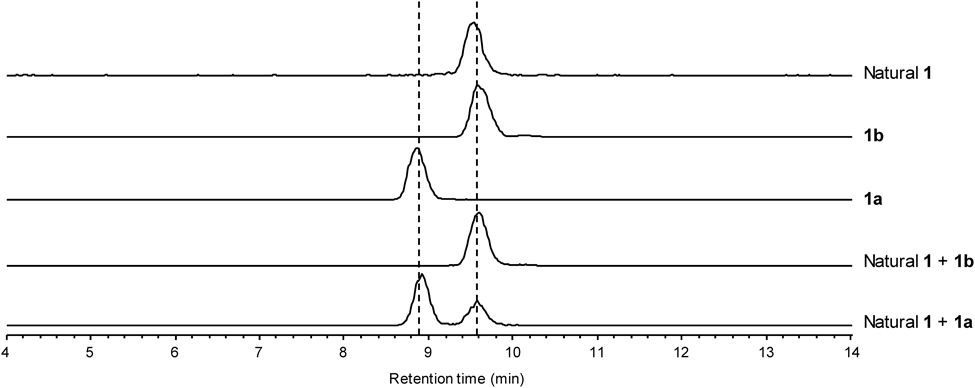

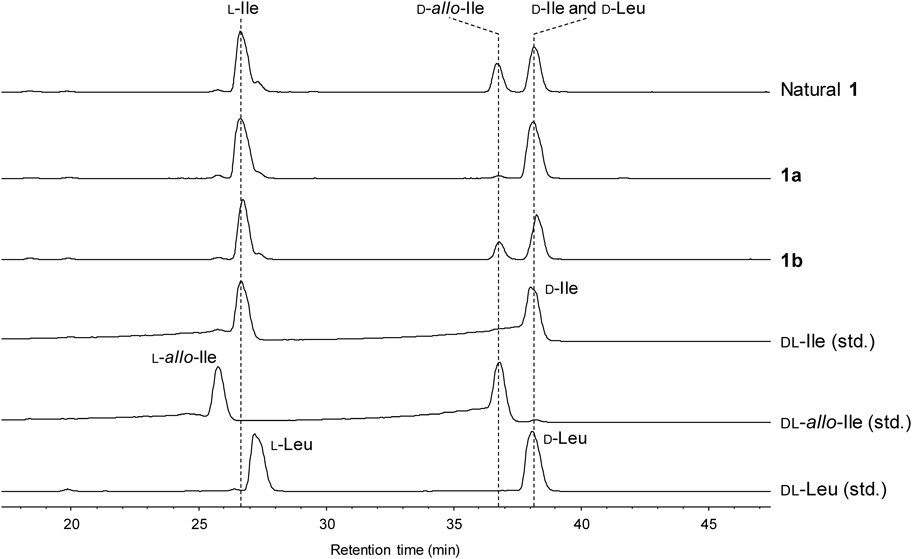

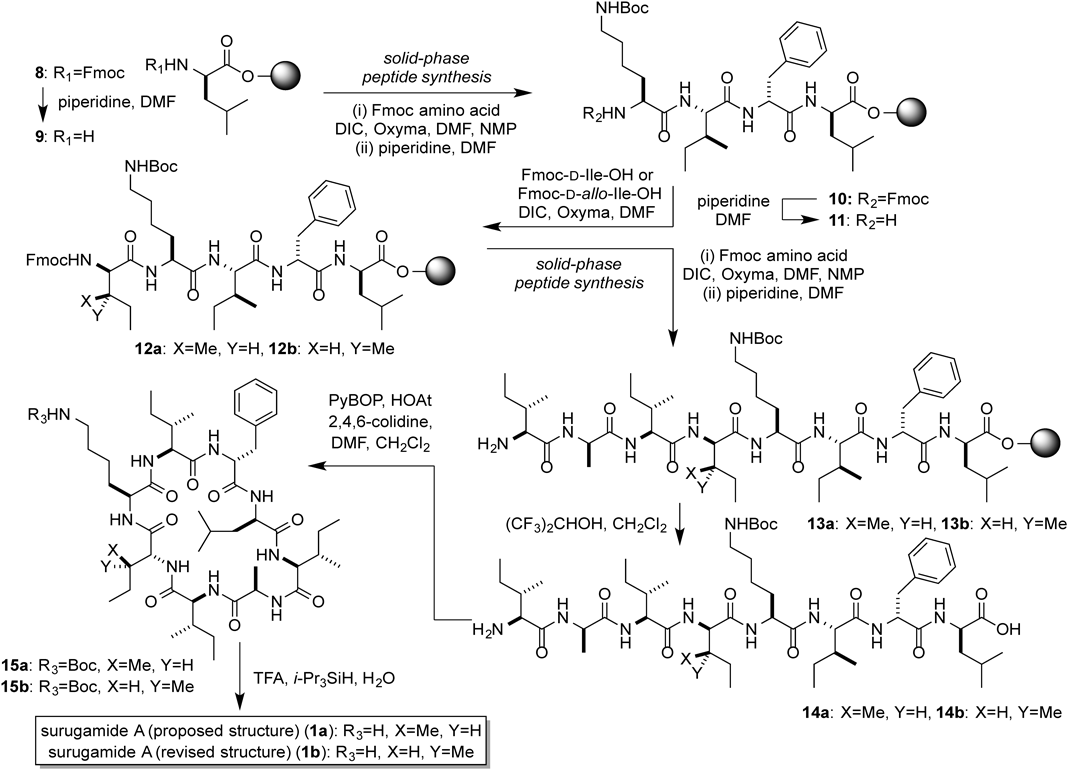

To confirm the structure of 1, we conducted the solid phase peptide synthesis of 1 from 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc)-D-Leu loaded on 2-chlorotrityl resin (8). The Fmoc group was deprotected by a treatment with piperidine to afford 9, and then three rounds of N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC)/Oxyma-mediated amide coupling and Nα-deprotection with piperidine yielded the resin-bound tetrapeptide 10. The amine 11 was conjugated to Fmoc-D-Ile-OH to afford 12a, and three further rounds of DIC/Oxyma-mediated amide coupling were performed to generate the resin-bound octapeptide (13a). Successive treatment of 13a with (CF3)2CHOH cleaved the peptide from the resin to give 14a, which was subsequently cyclized by using PyBOP and HOAt to produce the cyclic peptide 15a. Finally, 15a was treated with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)–i-Pr3SiH–H2O (95 : 2.5 : 2.5) to remove the tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) group, which yielded the originally reported structure of surugamide A (1a). However, the HPLC analysis revealed that the synthetic 1a was not identical to the natural surugamide A (Fig. 3). This result prompted us to compare the synthetic and natural 1 by the C3 Marfey’s method.12–14) The result did not exclude the possibility of the presence of a D-Ile residue, since the derivatized D-Ile and D-Leu were coeluted at almost the same retention time (Fig. 4). However, the data clearly showed the presence of a D-allo-Ile residue in the natural 1 (Fig. 4). According to the domain architecture of NRPS for surugamide A biosynthesis, the Cα-epimerization of Ile occurs only at the position 4, suggesting that 1 possesses D-allo-Ile residue instead of D-Ile in the position 4. To confirm this, 1 with the substitution of D-Ile to D-allo-Ile (1b) was synthesized in the same manner as 1a, as shown in Chart 1. As expected, the HPLC analysis revealed that 1b and the natural 1 are identical (Fig. 3), which was further corroborated by the C3 Marfey’s methods14) (Fig. 4).

Extracted ion chromatographs (EIC) for m/z 912.7 are depicted.

EICs for m/z 384.15 corresponding to derivatized DL-Leu, DL-Ile, and DL-allo-Ile are depicted.

The gray ball represents 2-chlorotrityl resin.

In the previous study,1) the configuration of Ile was identified by a subtle chromatographic difference between the 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-D-glucopyranosyl isothiocyanate (GITC) derivatives, resulting in the misassignment. In this sturdy, our synthetic efforts confirmed that 1 possesses D-allo-Ile at position 4, instead of D-Ile. Judging from the commonality of the biosynthetic pathways, the D-Ile residue present in other derivatives, such as 3–5, should also be corrected to D-allo-Ile.

1H- and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded on a JEOL ECA 500 (500 MHz for 1H-NMR) spectrometer. Chemical shifts are denoted in δ (ppm) relative to residual solvent peaks as internal standards (dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-d6, δΗ 2.50, δC 39.5). Electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS spectra were recorded on a Thermo Scientific Exactive mass spectrometer. Optical rotations were recorded on a JASCO P-1030 polarimeter. LC-MS analyses were performed with a SHIMADZU HPLC system equipped with a LC-20AD intelligent pump coupled with an amaZon SL-NPC spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics). All reagents were used as supplied unless otherwise stated. Column chromatography was performed using 40–50 µm Silica Gel 60N (Kanto Chemical Co., Inc.).

Procedure for Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS)Step 1The Fmoc group of the solid supported peptide was removed by using a 20% piperidine–N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) solution (10 min, room temperature).

Step 2The resin in the reaction vessel was washed with DMF (×3) and CH2Cl2 (×3).

Step 3To the solution of carboxylic acid (4 eq) were added DIC (4 eq, 0.50 M in NMP) and Oxyma (4 eq, 0.50 M in DMF). After 2–3 min of pre-activation, the mixture was injected into the reaction vessel. The resulting mixture was stirred for 30 min at 37°C.

Step 4The resin in the reaction vessel was washed with DMF (×3) and CH2Cl2 (×3).

Amino acids were condensed onto the solid support by repeating Steps 1–4.

Peptides 13a and 13bThe 2-chlorotrityl resin (156.0 mg, 0.25 mmol) in a Libra tube was swollen with CH2Cl2, and then the excess solvent was removed by filtration. To the resin was added a solution of Fmoc-D-Leu-OH (176.7 mg, 0.50 mmol) and i-Pr2NEt (262 µL, 1.50 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.5 mL), and the mixture was stirred for 30 min. The reaction mixture was filtered, washed with DMF (×3), CH2Cl2 (×3), and methanol. The Fmoc-D-Leu-2-chlorotrityl resin (50.8 mg, 0.05 mmol) in the Libra tube was swelled in CH2Cl2 for 1 h, and then subjected to 7 cycles [Fmoc-D-Phe-OH, Fmoc-L-Ile-OH, Fmoc-L-Lys-OH, Fmoc-D-Ile-OH (for 1a) or Fmoc-D-allo-Ile-OH (for 1b), Fmoc-L-Ile-OH, Fmoc-D-Ala-OH, Fmoc-L-Ile-OH] of the SPPS protocol (steps 1–4) to afford the mixture of the resin-bound peptides 13a or 13b.

Surugamide A (proposed Structure: 1a and Revised Structure: 1b)To peptides 13a was added CH2Cl2–(CF3)2CHOH (= 70 : 30) (0.5 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred for 20 min, and then filtered. This procedure was repeated twice. The filtrate was azeotropically dried with toluene (×3) to afford a crude mixture of peptide 14a, which was used in the next reaction without further purification. To a solution of peptide 14a in CH2Cl2–DMF (= 9 : 1) (25 mL) were added 2,4,6-collidine (26 µL, 0.196 mmol), HOAt (13.5 mg, 0.100 mmol), and PyBOP (52.4 mg, 0.100 mmol), and then the reaction mixture was stirred for overnight. The solvent was removed and the residues was dissolved in EtOAc and saturated aqueous NH4Cl. The resulting mixture was extracted with EtOAc (×3), washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated to give the crude 15a. To the residue was added a mixture of TFA–H2O–iPr3SiH (= 95 : 2.5 : 2.5) (1.0 mL), and the mixture was stirred for 1 min for the removal of the Boc group. The reaction mixture was diluted with Et2O (24 mL), and centrifuged at 3500 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and then Et2O layer was removed by decantation. This procedure was repeated twice. The crude 1a was purified by reversed-phase HPLC to afford 1a (21.1 mg, 46% for 18 steps) as a white solid.

1a[α]D19 −2.98 (c = 0.1 MeOH); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): see Fig. S1; 13C-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): see Fig. S2; high resolution (HR)-MS (ESI) Calcd for C48H82N9O8+ [M + H]+ 912.6281. Found 912.6275.

1bCompound 1b (18.7 mg) was synthesized from 13b in the same manner as 1a in 41% yield for 18 steps. [α]D21 −3.85 (c = 0.1 MeOH); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): see Fig. S3; 13C-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): see Fig. S4; HR-MS (ESI) Calcd for C48H82N9O8+ [M + H]+ 912.6281. Found 912.6278.

Analytical ConditionsFor the comparison of the natural surugamide A (1) and the synthetic compounds 1a, and 1b, the samples were analyzed by an LC-MS system with a SHIMADZU HPLC system coupled with an amaZon SL-NPC spectrometer. The samples were separated by chromatography on COSMOSIL 5C18-AR-II (4.6 i.d. × 150 mm) (Nacalai Tesque) using H2O–MeCN (55 : 45) + 0.05% TFA as the mobile phase (flow rate: 0.8 mL/min).

Total Hydrolysis and Derivatization with FDAAA portion of 1a or 1b was hydrolyzed in 6 M HCl at 110°C overnight. The solution was dried under a N2 stream and dissolved in H2O. To the solution were added 100 µL of 1% FDAA (2,4-dinitro-5-fluorophenyl-L-alaninamide) in acetone and 20 µL of 1 M NaHCO3. The reaction mixture was stirred at 50°C for 30 min and quenched with 10 µL of 2 M HCl. The FDAA-derivatized amino acids were analyzed as described below. Samples were injected into an Agilent Zorbax SB-C3 (4.6 i.d. × 150 mm) column and separated using H2O with a 5% isocratic modifier of 1% formic acid in MeCN as mobile phase A, and MeOH with a 5% isocratic modifier of 1% formic acid in MeCN as mobile phase B. The column was eluted in a 0.8 mL/min, linear gradient mode from 30% to 60% over 50 min for mobile phase B.14)

This work was partly supported by the Takeda Science Foundation, the Asahi Glass Foundation, the SUNBOR GRANT, the NOASTEC Foundation, the Akiyama Life Science Foundation, the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED Grant Number 18061402) and Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan (JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP16703511, and JP18056499).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The online version of this article contains supplementary materials.