- Issue 6 Pages 719-

- Issue 5 Pages 615-

- Issue 4 Pages 453-

- Issue 3 Pages 311-

- Issue 2 Pages 143-

- Issue 1 Pages 1-

- |<

- <

- 1

- >

- >|

-

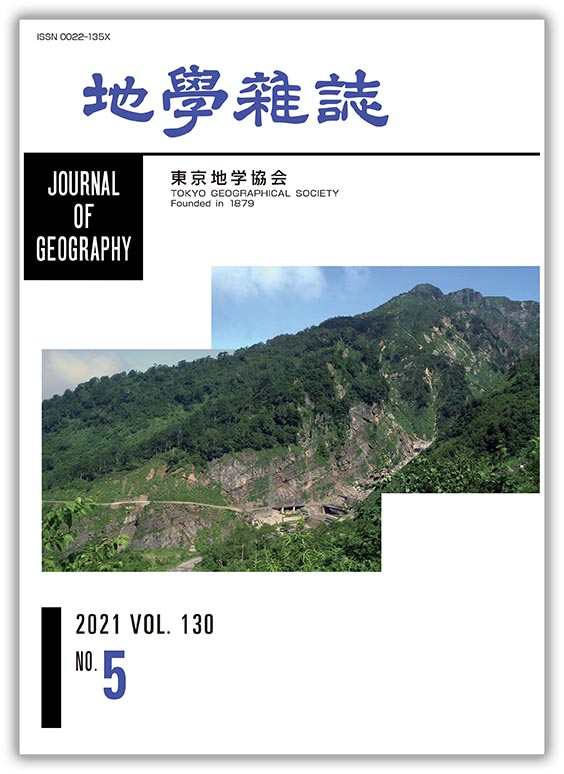

2021Volume 130Issue 5 Pages Cover05_01-Cover05_02

Published: October 25, 2021

Released on J-STAGE: November 17, 2021

JOURNAL FREE ACCESSThe Tetori Group is the thickest succession of Mesozoic terrestrial strata in Japan. The middle to upper parts of the Tetori Group crop out at the south side of Mt. Hakusan. The lateral variation of facies in formations of the Tetori Group led to complex naming, which has now been rationalized to reflect a coherent understanding of the Tetori Group architecture. The photograph shows the Kuwajima Formation, taken from the southeast, where it consists of northwest dipping, alternating beds of sandstone and mudstone, overlain by the sandstone of the Amagodani Formation. These strata dip along the ridge to lower elevations than at this location, where sandstone of the Otaniyama Formation, which underlies the Kuwajima Formation, is exposed. This sequence can be traced to the type section of the Tetori Group in the Shokawa area. The location of this photograph is Yunotani, located upstream on the Tedori River, Shiramine District.

(Photograph: Kazuto KOARAI, Photographed on July 22, 2004;

Explanation: Masaki MATSUKAWA)

View full abstractDownload PDF (2267K)

-

Ken-ichi KANO, Akira MIYASAKA, Genjyu YAMAMOTO, Kenji KUSUNOKI2021Volume 130Issue 5 Pages 615-632

Published: October 25, 2021

Released on J-STAGE: November 17, 2021

JOURNAL FREE ACCESSThe Suwa Basin is believed to be a typical pull-apart basin formed by the 12 km left-lateral motion on the Itoigawa–Shizuoka Tectonic Line active fault system. The starting age of the basin subsidence is considered to be after the violent volcanisms that formed the Lower Pleistocene Enrei Formation (Fm) distributed in and around the basin. However, the history of the basin development is still controversial mainly because of the insufficient geochronological data on the Enrei Fm in the SW Suwa Basin. The results of K–Ar dating are presented for two samples of andesite lavas of the Enrei Fm exposed on the northeastward-dipping slope of the SW Suwa Basin. One gives an age of 2.03 ± 0.19 Ma and the other an age of 1.51 ± 0.16 Ma. The former age corresponds closely to the oldest age of the Enrei Fm to the NE Suwa Basin, and suggests that the coeval and widespread initial volcanism at both sides of the basin occurred during the early Early Pleistocene (Gelasian) before the basin subsidence. The latter age closely corresponds to the peak periods of volcanic activity of the Enrei Fm. These lines of evidence suggest that the basin started to subside after 1.5 Ma, and that the position of basal unconformity, stratigraphy and geologic structures of the Enrei Fm in the SW Suwa Basin need to be re-examined.

View full abstractDownload PDF (8891K) -

Haruka TANI, Masanobu SHISHIKURA2021Volume 130Issue 5 Pages 633-652

Published: October 25, 2021

Released on J-STAGE: November 17, 2021

JOURNAL FREE ACCESSWe present the detailed distribution of liquefaction during the 1948 Fukui Earthquake in the central part of Fukui City by interpreting air-photographs taken immediately after the earthquake. Comparing this result with the liquefaction hazard map published by Fukui City, the actual distribution of liquefaction is not consistent with the risk assessment. The reason for this contradiction is that because the liquefaction hazard map of Fukui City was evaluated based only on information about the thickness of soft sediments. The results of the current study are also compared with geomorphic classification maps published by Geographical Information Authority of Japan, the land condition map, and the landform classification map for flood control (the first edition and the updated edition), respectively. They show that the liquefaction distribution overlaps with micro-topography such as the former river channel and the natural levee where liquefaction is likely to occur. From these comparison results, the importance of considering micro-topography when preparing a liquefaction hazard map can be recognized, and it is effective to refer to previously published geomorphic classification maps. However, since these maps are created for various purposes and have slightly different interpretations of micro-topography, multiple maps should be integrated to assess liquefaction potential.

View full abstractDownload PDF (12318K) -

Masaki MATSUKAWA2021Volume 130Issue 5 Pages 653-681

Published: October 25, 2021

Released on J-STAGE: November 17, 2021

JOURNAL FREE ACCESS

Supplementary materialThe Tetori Group comprises significant Mesozoic (middle Jurassic–early Cretaceous) marine and terrestrial strata in East Asia. A facies analysis of the group is conducted to reveal the development of the Tetori sedimentary basin. The Tetori Group in the Mt. Hakusan Region is mainly distributed in three areas: the Kuzuryugawa Area in Fukui Prefecture and the Shiramine and Shokawa districts in the Hakusan Area in Ishikawa and Gifu prefectures. Seven lithofacies associations are recognized, which represent the deposition in talus and proximal alluvial fan, gravelly braided river and alluvial fan, sandy braided river, lacustrine delta, estuarine, shoreface, and inner shelf environments. Based on the characters and spatio-temporal distribution of these lithofacies associations across the basin in the three areas, the group is interpreted to have developed in four stages. Stage 1 is represented by the lower part of the Tetori Group in the Kuzuryugawa Area in the southern part of the basin, and shows, in ascending order, talus and proximal alluvial fans, inner shelf, shoreface, and alluvial fan facies. Stage 2 represents the lower middle part of the group in the Shokawa District in the northeastern part of the basin, and shows a change from estuarine, shoreface to inner shelf, and back to shoreface facies. Stage 3 is recognized in the middle part of the group in both the Shiramine and Shokawa districts in the northwestern and northeastern parts of the basin, respectively. Stage 3 was initially formed as talus and proximal alluvial fan, gravelly braided river and alluvial fan, and sandy braided river facies, and was later changed to lacustrine delta, sandy braided river, and gravelly braided river and alluvial fan facies, and back to lacustrine delta and sandy braided river facies in ascending order in the Shiramine District, and was initially formed as estuary and shoreface facies, and was later changed to estuary, lacustrine delta and sandy braided river facies in ascending order in the Shokawa District. Stage 4 is represented by the upper part of the group in all three areas, and shows talus and alluvial fan, gravelly braided river and alluvial fan, and sandy braided river facies. The Tetori basin reflects an upheaval of the basin forming an inter-mountain basin. This supports the hypothesis of a juxtaposition of late Jurassic to earliest Cretaceous accretionary complexes along the eastern margin of the Asia continent during the Hauterivian (Early Cretaceous).

View full abstractDownload PDF (5474K) -

Hiroshi MORIWAKI, Toshiro NAGASAKO, Takehiko SUZUKI, Satoshi TERAYAMA, ...2021Volume 130Issue 5 Pages 683-706

Published: October 25, 2021

Released on J-STAGE: November 17, 2021

JOURNAL FREE ACCESSCoastal sand dunes dating to the latter part of the late Pleistocene were constructed at substantially lower sea levels on Kikaijima Island. They are preserved because of large-magnitude uplifts ascertained from occurrences of outstanding late Pleistocene and Holocene coral terraces. In addition, because Holocene sand dunes occur close to those of Marine Oxygen Isotope Stage 3 (MIS 3), the island is ideal for examining the environments of the formation of sand dunes, which were constructed under different climatic and sea-level conditions. Distributional and depositional features of sand dunes are clarified, and their chronology is constructed on the basis of tephrochronology, 14C dating, and chronological relationships of the sand dunes with marine terraces of known age. The environments of sand-dune formation on Kikaijima are examined in relation to climatic and sea-level records within regional and global contexts. Nine tephra layers are recognized. These include two widespread tephras, Kikai-Akahoya tephra (K-Ah) and Aira-Tn tephra (AT). The other seven tephras, consisting of fine ash layers, are newly recognized and named Kikaijima-1 tephra (Kj-1) to Kikaijima-7 tephra (Kj-7), of which the upper six, lying between K-Ah and AT, are aged from 13,000 to 30,000 cal BP. Holocene sand dunes began to form at c. 8,000 cal BP before the culmination of maximum Holocene sea-level rise. This is earlier than dune formation on other coasts of the Japanese Islands, where formation was generally after the culmination of maximum Holocene sea-level rise. The earlier formation on Kikaijima Island is probably due to coastal emergence caused by the conspicuous uplifts of Kikaijima and the high production of calcareous beach sands sourced from coral and foraminiferal and other materials. Late Pleistocene sand dunes, predominantly distributed at the southwestern part of Kikaijima Island, were formed in MIS 3. These dunes consist of longitudinal and parallel dunes. The largest longitudinal dunes on the lowest MIS 3 terraces, at the northern area of the southwestern part of Kikaijima Island, were formed in late MIS 3, c. 40 to 32 ka, while small and parallel sand dunes on the upper MIS 3 terraces were formed in early MIS 3. The occurrence and chronology of the Holocene and late Pleistocene sand dunes suggest that their formation on Kikaijima Island is mainly related to the occurrence of coastal sandy beaches during sea-level high stands. Although Holocene sand dunes are related to Holocene high stand, those of MIS 3 are related to high stands during cycles of sea-level fluctuations in MIS 3. The longitudinal landform of the sand dunes recognized in the late MIS 3 suggests that the prevailing winds in MIS 3 were stronger than in the Holocene. This study provides critical data for constructing a chronological framework that integrates various aspects of palaeoenvironments, as well as human interactions and responses in southern Kyushu.

View full abstractDownload PDF (4517K) -

Tomohito NAKANO, Yukio ISOZAKI, Yukiyasu TSUTSUMI2021Volume 130Issue 5 Pages 707-718

Published: October 25, 2021

Released on J-STAGE: November 17, 2021

JOURNAL FREE ACCESS

Supplementary materialU–Pb ages of detrital zircons are measured for two sandstones of the Domeki Formation (Fm) in the Shimanto belt, western Kochi, which represent bench deposits on the Paleogene fore-arc slope in SW Japan. The results show that both samples are replete with Paleocene and Late Cretaceous zircons, and they have extremely small quantities of pre-Cretaceous grains. This indicates that the provenance of the Domeki Fm was occupied mainly by felsic igneous rocks of the San-in belt in SW Japan, i.e., coeval volcanic arc. The age spectrum of zircons in the Domeki Fm is almost identical to those of coeval sandstones deposited in the main fore-arc basin (uppermost Izumi Group in the Kii peninsula, and Kanohara Conglomerate/Yorii Fm in Kanto). This suggests the ubiquitous supply of terrigenous clastics of the monotonous composition into the Paleocene fore-arc domain, including both the main fore-arc basin at the continent side and minor bench basins at the trench side, for more than 80 km across the arc from the southern margin of the Ryoke belt to the central Shimanto belt. Also confirmed is the stable and continuous deposition of voluminous arc-derived clastics on the fore-arc of SW Japan from the Late Cretaceous to Paleocene for more than 1000 km along the arc. The present data constrain the timings of two large-scale tectonic episodes in Paleogene SW Japan, i.e., the initiation of the Median Tectonic Line between the Ryoke and Sanbagawa belts and the first surface exposure of high-P/T Sanbagawa schists, to have been no earlier than the Paleocene/Eocene boundary (ca. 56 Ma).

View full abstractDownload PDF (2139K)

- |<

- <

- 1

- >

- >|